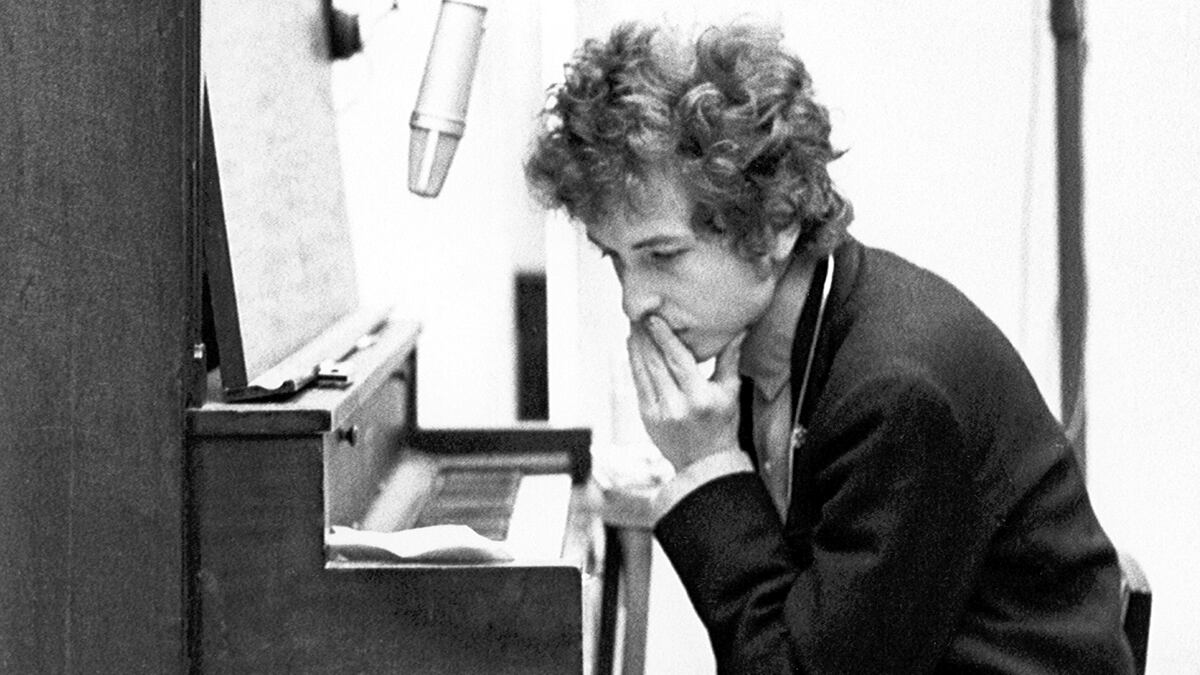

We begin with Bob Dylan. Dylan in 1965, during the low point of his career, as Jonah Lehrer writes in his new book Imagine. He was sick of his sound, ready to give up on the whole enterprise. He’d found commercial success, but he’d lost his taste for it. He no longer had the sense of doing something original. He was going to quit music, he said, and he took off to a secluded cabin in the woods. He didn’t bother to bring his guitar.

It was here, alone in his cabin, feeling irrevocably stumped, that Dylan, as if out of nowhere, had his major breakthrough. The lyrics came rushing out of him. He scrambled to write them all down. The result would transform his career. “Like a Rolling Stone,” with its vivid, raw, unrestrained lyrics, changed rock n’ roll, breaking the rules of tidy song composition that had previously dictated the shape of most pop songs.

“It is often only at this point, after we’ve stopped searching for the answer, that the answer often arrives,” Lehrer writes. “And when a solution does appear, it doesn’t come in dribs and drabs; the puzzle isn’t solved one piece at a time. Rather, the solution is shocking in its completeness.”

Just 30, Lehrer has become something of an empire unto himself in the world of science journalism. He has a column in the Wall Street Journal, a blog at Wired Magazine, and regularly contributes to The New Yorker. He is now the author of three books. His focus is neuroscience, his persona affable, reasonable, and calm.

In his new book, Lehrer takes a Gladwell-esque approach, weaving together examples of creativity—including people, places, and spaces—with the science that might explain it. So Lehrer turns to neuroscience to see what it has to say on the subject of how an insight like Bob Dylan’s suddenly comes to surface.

“One of the surprising lessons of this research is that trying to force an insight can actually prevent the insight. While it’s commonly assumed that the best way to solve a difficult problem is to relentlessly focus, this clenched state of mind comes with hidden cost: it inhibits the sort of creative connections that lead to breakthroughs,” he writes.

A relaxed state of mind—marked by alpha wave activity—research suggests, allows the brain’s right hemisphere, which specializes in big picture connections, to make itself heard, resulting in the sudden ability to look at a problem differently and see the solution.

By contrast, Lehrer gives us the example of W.H. Auden, the 20th-century poet and known amphetimine devoteé. Auden’s modus operandi was relentless, focused, attention, forever whittling away at his poems until they turned into jewels.

“The reality of the creative process is that it often requires persistence, the ability to stare at a problem until it makes sense,” Lehrer writes. “The answer won’t arrive suddenly, in a flash of insight. Instead, it will be revealed slowly, like a coastline emerging from the clouds.”

This type of concentrated focus, as exemplified by Auden in his daily Benzedrine grind, springs from a different neural source than Dylan’s free floating attention. It’s working memory—the ability to hold many things in mind at once—that becomes most central to the kind of effortful attention Auden applied to his poetry.

Yet, says Lehrer, the work that gets done this way is distinct from the relaxed, right hemisphere centric approach. “These new ideas are not epiphanies,” he writes. “The connections made in working memory don’t feel mysterious, like an insight, or shock us with their sudden arrival. Instead, these creative thoughts tend to be minor and incremental—one can efficiently edit a poem but probably won’t invent a new poetic form. . . . We might miss the forest, but we can clearly see each tree.”

The Dylan mindset and the Auden mindset can be contrasted, Lehrer writes, in terms of the distinctive brain processes at work in either case. The former open, relaxed, receptive, the latter, white knuckled focus, bearing down on the task at hand. Both are components of the creative process, and, as a person muddles along the confusing path from idea to execution, each mindset has its time and place.

The question becomes, how do we know which mindset to cultivate? “The human mind has a natural ability to diagnose its own problems, to assess the kind of creativity that’s needed,” Lehrer observes.

Continuing on, we hear from Yo Yo Ma and David Byrne. We visit 3M, then we’re off to Silicon Valley, for a tour of Pixar, the wildly successful animated movie company responsible for Toy Story and Finding Nemo, among many others.

Lehrer carefully dissects the Pixar way, from its office space, which is open and communal and forces, by its physical design, constant interaction among its employees, to its daily rituals of constructive criticism. (As opposed to the more traditional brainstorming, where every idea must be treated as equally good—an approach that has been shown to be completely ineffective.)

It’s an informative, detailed look at the process that has worked for Pixar, but it is far from clear that what has worked at Pixar would also work at a different company. In fact, just last month, in a piece on “Groupthink” in the New York Times, Susan Cain argued for the anti-Pixar approach.

“Studies show that open-plan offices make workers hostile, insecure and distracted,” Cain wrote. “They’re also more likely to suffer from high blood pressure, stress, the flu and exhaustion. And people whose work is interrupted make 50 percent more mistakes and take twice as long to finish it.”

But regardless of which office layout is truly the most conducive for creativity, the very question is interesting to consider, as is this book for anyone who cares about creativity. And pleasurably, too—Lehrer writes with a lovely, buoyant vibrancy that keeps his reader steadily afloat.

His fundamental message is similarly pleasing. Everyone is a “creative type,” and there are techniques for accessing that innate capability, from long walks to travel to unplanned conversations with strangers.

To illustrate the theme that creativity is latent in all of us, Lehrer describes a neurological disease called frontotemporal-dementia. In this degenerative illness, patients lose the function of the left half of their brain. As a result, their more free-wheelin’ right hemisiphere is emboldened, sprung from the logical left-brained confines formerly imposed on it. Lehrer cites cases of these patients who suddenly find themselves, for the first time in their lives, overcome with the urge to create, rushing out to buy art supplies, then obsessively churning out painting after painting.

“This awful affliction,” Lehrer writes, “comes with an uplifting moral, which is that all of us contain a vast reservoir of untapped creativity.”

What Lehrer doesn’t mention about these frontotemporal-dementia patients is that the ones who suddenly find themselves feverish with artistic drive represent the overwhelming minority. Most people who develop frontotemporal-dementia do not become impromptu Picasso’s. These patients are not feel-good allegories for the potential within all of us. Lehrer’s spin is a honeyed interpretation that verges on the disingenuous. It’s a crowd-pleasing notion in a crowd-pleasing book.

In keeping with this ethos, Lehrer consistently measures creativity by how much money was made, how many awards won. Creativity and commercial success are intertwined in this book. It can feel like an unnervingly business-minded attitude, one that reflects the commodification of creativity that we, as a culture, seem to have embraced.

Relax your mind to unleash those lucrative alpha waves; mobilize your pre-frontal cortex and make a million bucks.

This is creativity for capitalists—which somewhat takes away from the fun.