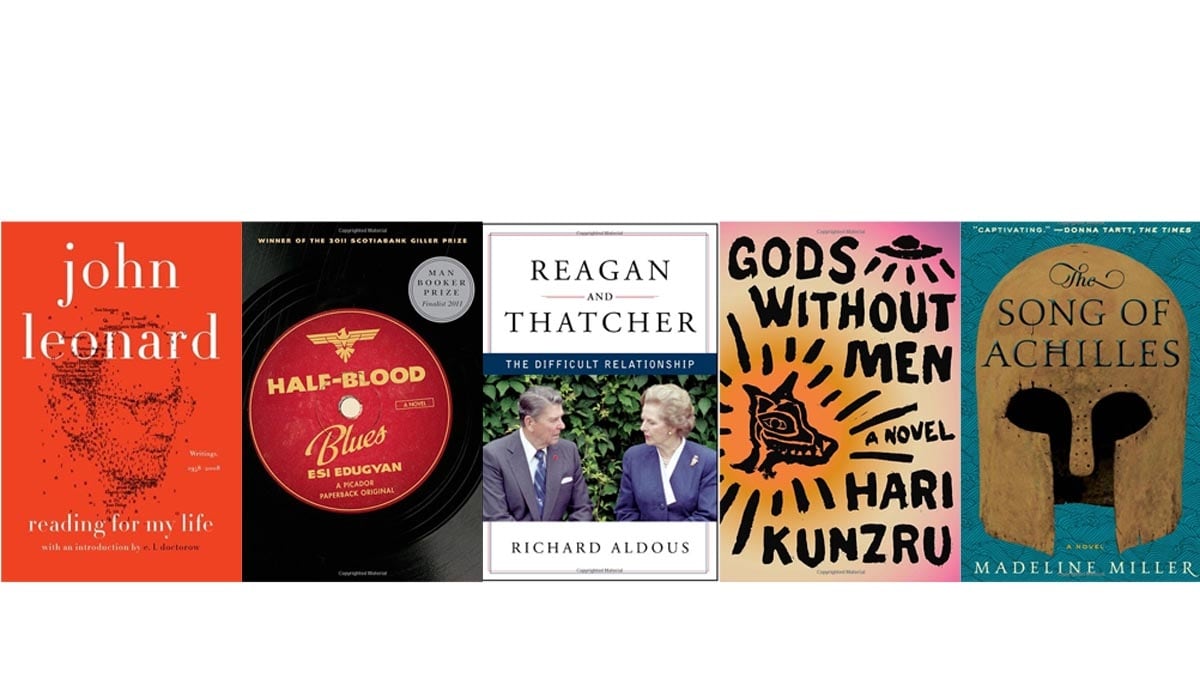

In Madeline Miller’s debut novel, we can indulge our curiosity in Achilles’s love affair with Patroclus, as well as feel what it is like to believe that gods live among us.

The ancient Greeks took their myths seriously, and they believed they were living among gods. The exact spot where Aphrodite was born of foam is just off the coast of Kythira, and anyone can visit it. At the end of the day, Pegasus always returned to a stable in Corinth. One could have found men who were said to have fought alongside Heracles. It’s not easy to comprehend this attitude. (Unless one considers the equivalent in today’s religions—discoveries of the finger bones of the Buddha, claims of being the son of God.) Along comes the debut novel The Song of Achilles, a retelling of the Trojan War (including The Iliad, but also what came before and after the epic) through the eyes of Patroclus, Achilles’s gay lover. Here, we can sense for ourselves the awe that one might feel in the presence of the bowman Philoctetes, “a comrade of Heracles,” or what it means for Achilles to be the son of Thetis, the silver-footed sea nymph. The prose of any reimagining of The Iliad has the danger of sounding like a 10th-grader parodying Homeric conventions (see Elizabeth Cook’s Achilles a decade earlier), and the most well-known episodes, like Achilles’s battle with Hector, can be a bore. (Miller has the good sense of making it brief; anyway, for most of The Iliad, Achilles never lifts a weapon.) But they keep coming; we will never cease explaining Achilles’s bizarre wrath, though it’s long been considered an impossible task to humanize such a cold and misanthropic figure. In a revisionist take, Miller rejects The Iliad’s interpretation that the great warrior chose a brief and glorious life, and struggled to fill it with meaning. He simply wanted to wile away the days with his lover. But it was not meant to be: he was a son of celebrities, a boy who never felt anger because “no one has ever tried to take something from me,” (to disastrous consequences later, of course), and a gentle, naive soul who reluctantly courted but was largely dragged onto the world stage—in other words, an ancient Brangelina. He didn’t stand a chance.

Reagan and Thatcher: The Difficult Relationship

The British prime minister had a more critical view of the American president than is generally reported, and through the Iron Lady’s eyes we might get a more accurate picture of the Great Communicator.

These endless days and nights of Santorum and Newt have us nostalgic for a time when large creatures known as Reaganite Republicans roamed the earth. Was Ronald Reagan truly a Great Communicator? Did he make more sense than Romney? In the cult of Reagan, yes. Even President Obama is a groupie. But Richard Aldous, a history and literature professor at Bard College, uses Margaret Thatcher to dismantle the myth of the American president—and to dismantle the myth of their lock-stepped, best-friends relationship. It was more like a Balanchine-Stravinsky pas de deux, full of tension, crashing cymbals and shifting rhythms. Mostly, “he was more afraid of me than I was of him,” said the Iron Lady who would slam a copy of Viennese economist F.A. Hayek’s book hard on a table, showing off her intellect and ferocity at once. The chapter titles say a lot: “Even More of a Wimp than Jimmy Carter,” “Not a Great Listener.” Nevertheless, Reagan was a direct ancestor to today’s GOP candidates, and his coming brought about the extinction of the pro-choice, pro-government liberal Republican. An accurate picture of the Reagan-Thatcher dance does us all a favor.

Reading for My Life: Writings, 1958-2008

From the catholic mind of the enduring critic John Leonard: “It seems to me that my whole life I’ve been standing on some tower or a pillbox or a trampoline, waving the names of writers, as if we needed rescue.”

Speaking of dancing, only the late critic John Leonard, whose thoughts dart from one precisely placed allusion to another, and then to a third, fourth and fifth—usually within the same sentence—could describe a biography (David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street: the Life and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Farina, and Richard Farina) as “A Little Night Music scored for dulcimer and motorcycle. Or a pas de quatre, with wind chimes, love beads, and a guest-appearance entrechat by Thomas Pynchon.” It’s dead on, and great fun to read. Sure, sometimes you yearn for more exposition, but Leonard commands love and devotion, much like that required of a parent taking care of an ADHD child. As E.L. Doctorow observes in his introduction, Leonard was “a political animal,” and his television and media criticism rank among the most catholic ever (with a lowercase C). Not enough of them are included in this posthumous collection, which spans 50 years. But Leonard’s first love was literature, and he lavished attention on Maxine Hong Kingston, Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, and Michael Chabon, just to name a few, which ought to make clear his delicious taste.

A Weimar novel that haunts you with its syncopated blue notes long after the music has stopped—or perhaps because the music has stopped.

Are you familiar with the story of the Hot-Time Swingers, a multiracial jazz ensemble that made history with the record Half-Blood Blues, which dropped like a meteor in 1939 Berlin? The following summer, its hot trumpeter, Hieronymus Falk, was arrested by the Gestapo in a Paris café, and vanished thereafter. Never heard of him? You so wish this fiction to be real, that the history of some never-before-discovered band that hung out with Kurt Weill in Weimar Germany dropped on your lap, sticking its tongue out at Adorno. The young Canadian Edugyan’s second novel, which was a finalist for the 2011 Man Booker Prize and at last available stateside as a paperback, is the next best thing. It moves through the landscape of Europe’s (and America’s) dark history like a train toward its inexorable stop, 53 years later, the sound of Lohengrin, The Threepenny Opera, and West End Blues haunting the space between your ears.

The lord of Gods Without Men, an eerie novel of the Mojave Desert by the indelible writer Hari Kunzru, is not only space—but also time.

Often a foreigner can see America better than we ourselves see it—consider Tocqueville. The Briton Hari Kunzru is one such writer. He picks the Mojave as his center of inquiry, where things go to disappear, and out spins an eerie survey of the mythic landscape. (Think the Peter Weir film The Picnic at Hanging Rock and the songs of The Doors.) Jaz and Lisa, a New York couple, lose their autistic son, Raj, while on a trip to the desert. Manhattan is denser than an English muffin, but America is filled with emptiness. What is it like to stare into the void? Cormac McCarthy asked that same question, and both writers are obsessed with a space that resembles an unknown—or rather, unknowable—past. Each chapter is from a different time: 2009, 1947, 1871, 1969, 1775. There is freedom in these travels to the heart of darkness—but also, of course, a price.