A sense of romance encircles the concept of the lost novel, sequestered as it is for decades, maybe even centuries, in a dusty attic or library or briefcase, robbing the adoring public of a great writer’s unpublished work. When that writer is a legendary one, the discovery of such a manuscript can ripple through the literary world and rekindle the excitement generated by his or her most lauded work. In this respect, the publishing world has gotten lucky lately.

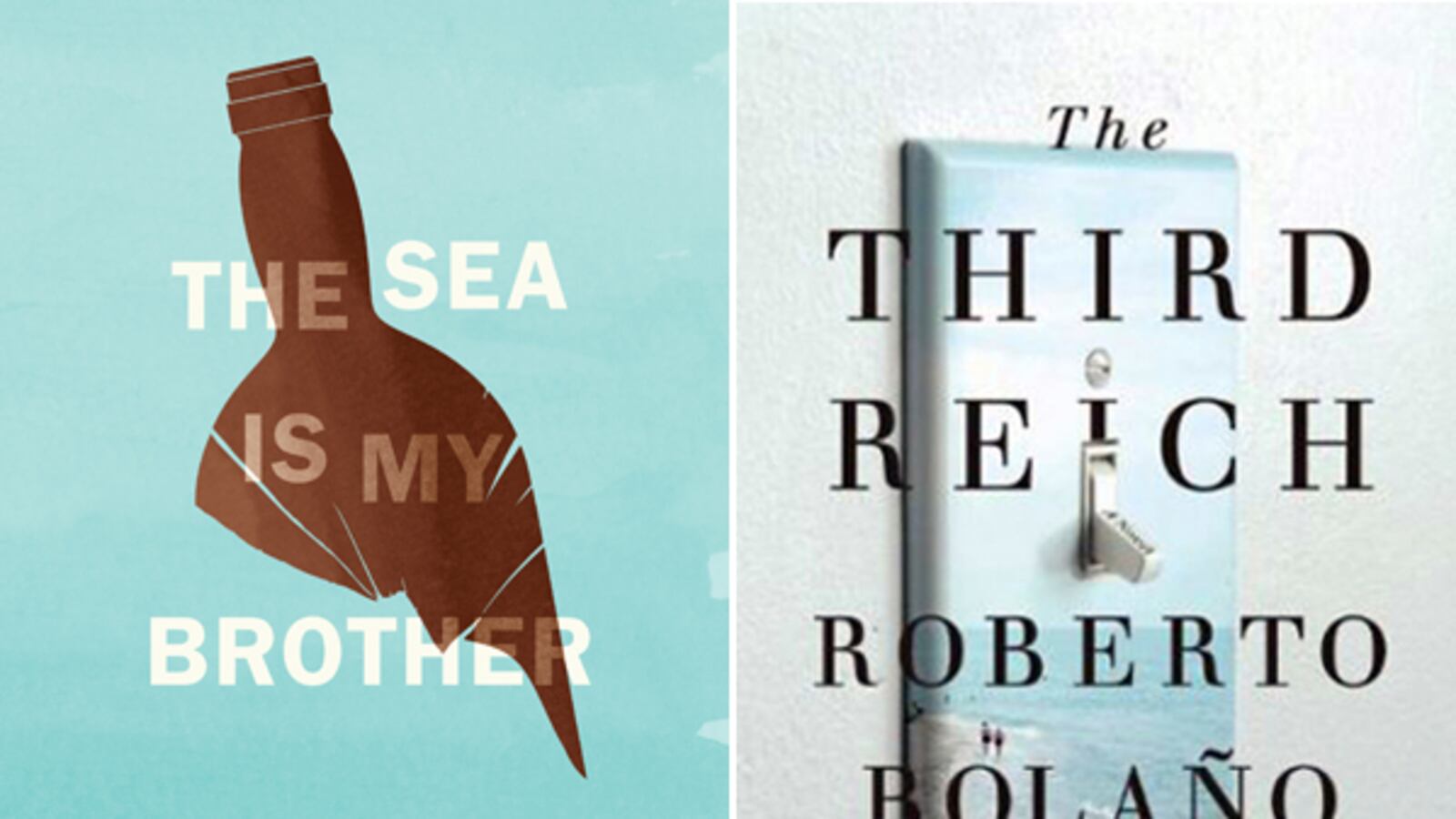

This month sees the U.S. publication of Jack Kerouac’s first and previously unpublished novel, The Sea Is My Brother, which comes on the heels of newly found and published novels by José Saramago, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and Roberto Bolaño.

These lost-and-found works are often early writings, first attempts to master the form by a future titan who would achieve success on subsequent tries, then bury that first clunky effort. Rarer is the lost masterpiece, although one does come to the surface occasionally, a victim of war (Suite Française), suicide (A Confederacy of Dunces), or even routine carelessness (The Pursued).

Here are 10 novels that were lost to the world, along with the fascinating stories behind their journey back into the light.

The Sea Is My BrotherBy Jack Kerouac

Kerouac was just 21 when he wrote The Sea Is My Brother, and it would be another 14 years before he wrote the novel that made him famous, On the Road. And by most accounts, he needed at least some of those years to develop the style that would eventually captivate an entire generation of readers. Discovered by his brother-in-law among Kerouac’s papers in 1992, the novel draws on the author’s brief tour of duty in the merchant marine in telling the story of two friends en route from Boston to Greenland on a merchant marine vessel. It was published in the U.K. late last year, and sees its U.S. publication this month.

Claraboya By José Saramago

Nobel winner José Saramago’s first attempt at a novel, Claraboya was rejected by a publishing house in his native Portugal in 1953. The sting of that first rejection kept him from writing another novel for almost 20 years. But decades later, after Saramago had attained widespread acclaim with novels like Blindness and The Stone Raft, the publisher discovered the manuscript during a move and scrambled to get his permission to publish it. For Saramago, it must have felt good to decline that offer. He then told his loved ones they could publish the novel if they wished after his death, which came two years ago. Claraboya, about a group of characters living in the same Lisbon apartment building, was published in Portuguese last year, and an English translation is currently in the works.

The Narrative of John SmithBy Arthur Conan Doyle

Before Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson came John Smith, although no one really knew about him for well over a century after he was first created by Arthur Conan Doyle. Reflecting on the manuscript, about a man sick with gout, Doyle spoke of his “horror if it were suddenly to appear again—in print.” He got his way until last year, when after purchasing the novel at a Christie’s auction for £47,800 in 2004, the British Library finally published it in the U.K. The extant version, though, is more than likely a recreation from the author’s memory of the original manuscript, the only copy of which was apparently lost in the mail on its way to a publisher.

Summer CrossingBy Truman Capote

Capote worked on his first novel on and off for years before finally setting it aside. He left it behind, along with a number of other papers, when moving out of a Brooklyn Heights apartment, but the superintendent fished them out of the trash and kept them in storage until his death, 50 years later. As her nephew went through her belongings, he came across the manuscript that Capote had claimed “he tore up.” The novel, about a young debutante cavorting in New York City in the summer of 1945, was finally published in 2005. Scarlett Johansson is set to direct the film adaptation.

The Third Reich By Roberto Bolaño

Unlike many unpublished first novels that turn up after an author’s death, this one, written in 1989 and discovered, quite literally it seems, in the bottom of a drawer in 2003, shows Bolaño already in command of his literary talent, writing about a German 20-something spending a summer week at a Spanish resort. There is no evidence of Bolaño sequestering the novel—in fact, he retyped the first 60 pages of it in 1995 when he got his first computer. The English translation came out in 2011, after a rare serialization in The Paris Review.

A Confederacy of DuncesBy John Kennedy Toole

Perhaps the lost novel with the saddest back story, the manuscript for this one was discovered by the author’s mother after his suicide at age 31, in 1969. Before that, the novel, about a bombastic, unemployed anti-hero living in New Orleans, made it into the hands of Robert Gottlieb, then at Simon & Schuster, who took interest in the manuscript but eventually shelved it. Toole reportedly took these and other rejections hard. After his suicide in Biloxi, Miss., his mother eventually got the manuscript into the hands of Walker Percy, who convinced the Louisiana State University Press to publish it.

Suite FrançaiseBy Irene Nemirovsky

Another lost novel whose story is laced with tragedy. Just before she was arrested and shipped off to Auschwitz, where she died a month later, Nemirovsky put the manuscript in a suitcase and gave it to her daughter, Denise, for safekeeping. Believing the manuscript to be a personal diary, Denise avoided reading it for three decades. Upon discovering she’d actually been holding onto a novel based on the very months leading up to her mother’s arrest, she still kept it under wraps for another 25 years. Her mother had been a famous writer in the 1930s after the publication of her first novel, David Golder. But as the war started, she was abandoned by friends and the public alike. Suite Française finally brought her back to renown with its publication in France in 2004 and subsequent English translation.

Paris in the Twentieth CenturyBy Jules Verne

At the advice of his publisher, Verne abandoned this novel, placing the manuscript into a safe, where it would remain unseen for more than a 100 years. In the meantime, the author would go on to fame for such novels as Journey to the Center of the Earth and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. But first, in 1863, Verne imagined the Paris of a century in the future, prophesying a modern world in which arts and literature had lost favor to the wonders of technology. Not until 1989 did Verne’s great-grandson discover the text, and it was finally published in 1994—a testament, perhaps, to the perseverance of literature in the face of the very technologies that Verne feared would stifle it.

The Pursued By C.S. Forester

The only novel on the list that was lost unintentionally. Accepted by his publisher in 1935, its release was delayed in order to avoid interfering with publicity for Forester’s other novels, which included The African Queen and the Hornblower series. During subsequent years, both author and publisher moved house, and neither was able to locate a copy of the manuscript. The Pursued finally resurfaced in 2002 as part of an overlooked lot of Forester items at a Christie’s auction, where it was noticed and bought by a Forester enthusiast. The Pursued was finally published in the U.K. late last year.

The InheritanceBy Louisa May Alcott

The Little Women author wrote this slim novel, about an orphan named Edith who is taken in by a wealthy family, in 1894, when she was only 17. She never tried to publish it, but for perhaps sentimental reasons, she held onto the manuscript her entire life. After Alcott died, it changed hands a couple of times without notice, landing in Harvard’s Houghton library in 1974. It sat there until 1988, when two researchers stumbled upon it while studying Alcott’s personal letters.