One day, Anna, the 5-year-old daughter of two “proudly secular, well-educated urban Danes,” asked her mother if God had created the world. Frederick, her father, carefully explained, “The world wasn’t created. It has always been here.” Anna didn’t buy it, so he went a little more in-depth: “Well, a long, long time ago there was this big bang and suddenly everything just appeared.” The girl thought about this, trying to wrap her mind around a concept we all have trouble with.

“God must have been surprised,” she said.

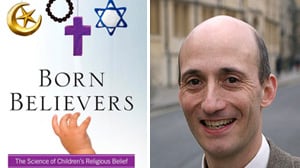

It’s an unforgettable anecdote and a perfect encapsulation of Justin Barrett’s argument in his new book, Born Believers: The Science of Children’s Religious Belief. Kids aren’t blank slates upon which we inscribe our religious or irreligious convictions. Rather, they arrive in the world with a strong, cognitively driven propensity for religious belief “preinstalled”—and, as in Anna’s case, it can be difficult to shake.

At first glance, it seems like the sort of books atheists and secularists everywhere would want to commit to memory. After all, Barrett, a psychologist at Fuller Theological Seminary who has dedicated his career to untangling the cognitive underpinnings of religious belief (his earlier book, Why Would Anyone Believe in God?, is an excellent primer on the subject), argues forcefully and convincingly that when it comes to kids’ brains, the deck is stacked against atheism. Children come into this world predisposed toward believing in supernatural entities—their “minds are naturally tuned up to believe in gods generally, and perhaps God in particular.” Drawing from a wide array of studies and experiments, including his own, Barrett shows that kids don’t need to be indoctrinated into religion, because their hardwiring all but guarantees that they will be believers, of a sort, whether or not their parents want them to be.

From the atheist perspective, this leads to some potentially fruitful arguments: we are led toward religious beliefs not because they are true, but by outdated components of our cognitive architecture, by evolutionary accidents that may no longer serve a purpose.

But in the simmering milieu of America’s culture wars, and in the wake of the rise of the “new atheists,” nothing is ever that simple. And that’s why Barrett, despite taking what is very much a rigorous, science-driven approach to his subject, finds himself at intellectual loggerheads with Richard Dawkins and many other atheists. That, and because he himself is a believer.

Barrett devotes a good chunk of Born Believers to debunking the indoctrination hypothesis, the idea, as he puts it in the book, that “children believe because their parents (and other trusted adults) act as if they believe, and talk as if they believe.” Dawkins is one of the staunchest purveyors of this view (or, rather, “evolved gullibility,” a close cousin of it), and he takes things a step further by arguing that it’s abusive to expose children to organized religion. As Barrett quotes from The God Delusion: “Even without physical abduction, isn’t it always a form of child abuse to label children as possessors of beliefs that they are too young to have thought about?”

Barrett clearly doesn’t think Dawkins has done his homework, that he is extending his political agenda into a research area where he’s unfamiliar. “I think that he is relatively unaware of the relevant research, especially the development research,” he said. “I don’t get the impression that he is up on his psychology of religion.”

“Why might that be? Well, I suspect that he just has other things to do.”

“He’s a biologist, a very good biologist from all accounts, who has this other life as a promoter of science and an opponent of religion,” Barrett said. “That maybe doesn’t give him enough time to really get to intimately know the relevant research in psychology.”

But isn’t it his responsibility as a public intellectual to make sure that his arguments are well-grounded empirical research? “I do think that insofar as he wants to make certain kinds of psychological claims, his credibility as an advocate of science would be much enhanced if he actually drew upon the relevant science,” said Barrett. “So would it be good for him? Yeah, I think it would be good for him.”

That said, Barrett wasn’t entirely uncharitable toward Dawkins. Since The God Delusion, he said, “he seems to have become more aware of some of the work that’s going on in cognitive science of religion and some of the developmental work, and his view of what’s going on in childhood seems to be a little more complex than it was now.”

The contretemps with Dawkins reveals the interesting flip side to atheists’ reaction to Barrett and his work: Yes, cognitive science of religion can be used to buttress the atheist cause. But it also strikes a blow against it, because it highlights the futility of some very popular notions about how to “cure” people of religion.

“The common discourse in the air out there is that it’s all about teaching,” said Barrett. “It’s all about our educational system. It’s all about our parenting style. It’s all about enculturation. This has been a common line” for a long time. “The cognitive revolution has never been able to get into the public mindset.”

If our brains evolved, as Barrett argues, to find religion much easier to grasp onto than nonreligion, then this isn’t simply a matter of education or culture. As popular as the atheist view that having kids read Carl Sagan and Sam Harris from an early age will lead to a profoundly secular society is, it isn’t backed up by science. Not when religious beliefs stem from such foundational parts of our cognitive architecture.

“The people who seem to have gotten angriest at me have been atheists,” said Barrett. He finds this perplexing. “I don’t know if what I’m arguing is all that deviant from what they’re arguing.”

It might have something to do with the fact that Barrett himself is a rather staunch believer.

“On these issues I’m a fairly traditional orthodox—little O—Christian,” he said. “I think there is a God who is interested in our behaviors. I think God principally acts in a sustaining fashion through natural processes ... that God does interact with us, which requires a little bit of Him acting contingently upon our behaviors and actions as well. I’m not so sure that God is in the business of finding us the best parking place”—here he was referencing an example of religious thinking from the book that I had mentioned—“but I don’t have any strong reason to think that if finding us a good parking place in a certain situation can strengthen our relationship and our dependence upon Him, then he might not use that.”

Barrett’s beliefs should be seen as completely separate from his work; he is an undisputed leader in his field (and it is a field, he pointed out, in which many of his fellow travelers, like Jesse Bering, are atheists). But his theism does clarify some of the tension between his work and popular atheism.

It’s understandable why the average American atheist, someone who is angry that fundamentalist beliefs have done a lot of damage in the world, that we’re still debating evolution in the U.S., might feel more sympathy to and connection with Dawkins’s work than Barrett’s. Dawkins, after all, is a crusading, outspoken advocate for atheism, so the fact that his stances on some rather complex psychological issues happen to be ill-informed may not register. Barrett, on the other hand, offers up rigorous but largely apolitical cognitive explanations for religion—and won’t dismiss the idea of God helping someone find a parking spot.

It’s no wonder that some of the loudest voices for the scientific method support Dawkins in this fight, even though he seems to ignore that method when it suits him.