Philip Klein of the Washington Examiner responds to my recent blog posts on healthcare with a 2-point answer.

POINT 1:

Over at the Daily Beast, David Frum writes about the question he would have posed during the Supreme Court's oral arguments if he had the chance. But in the process, he seriously distorts the concept of Social Security private comments in an attempt to liken them to the individual mandate:

For many years, libertarians like those at the Cato Institute have advocated replacing Social Security with a mandate on all citizens to save for their retirement in a privately managed account.

Question: If it's unconstitutional (as the challengers to the Affordable Care Act now argue) for government to require citizens to buy health insurance coverage from a private provider, how can it possibly be constitutional for government to require citizens to buy a retirement annuity from a private provider?

The logic of the challenger's case is that the only constitutionally permissible way to provide for social needs is through a big government tax-and-redistribution program.

If the healthcare mandate is unconstitutional, how can compulsory private retirement accounts be permissible?

Frum might have an interesting point here, if his description of private accounts were remotely accurate. But he neglects a key point—those accounts would be completely voluntary. Under typical proposals, workers would have the choice as to whether to stay in the current Social Security system, or divert their payroll taxes into personal accounts (the big difference among proposals tends to be how much of their taxes they can divert). In fact, the Cato Institute article Frum links to, written by Chile's former secretary of labor and social security, describes his nation's experiment with personal accounts this way: "Chile allowed every worker to choose whether to stay in the state-run, pay-as-you-go social security system or to put the whole payroll tax into an individual retirement account." (Emphasis mine.)

This is a far cry from "compulsory private retirement accounts," as Frum describes them.

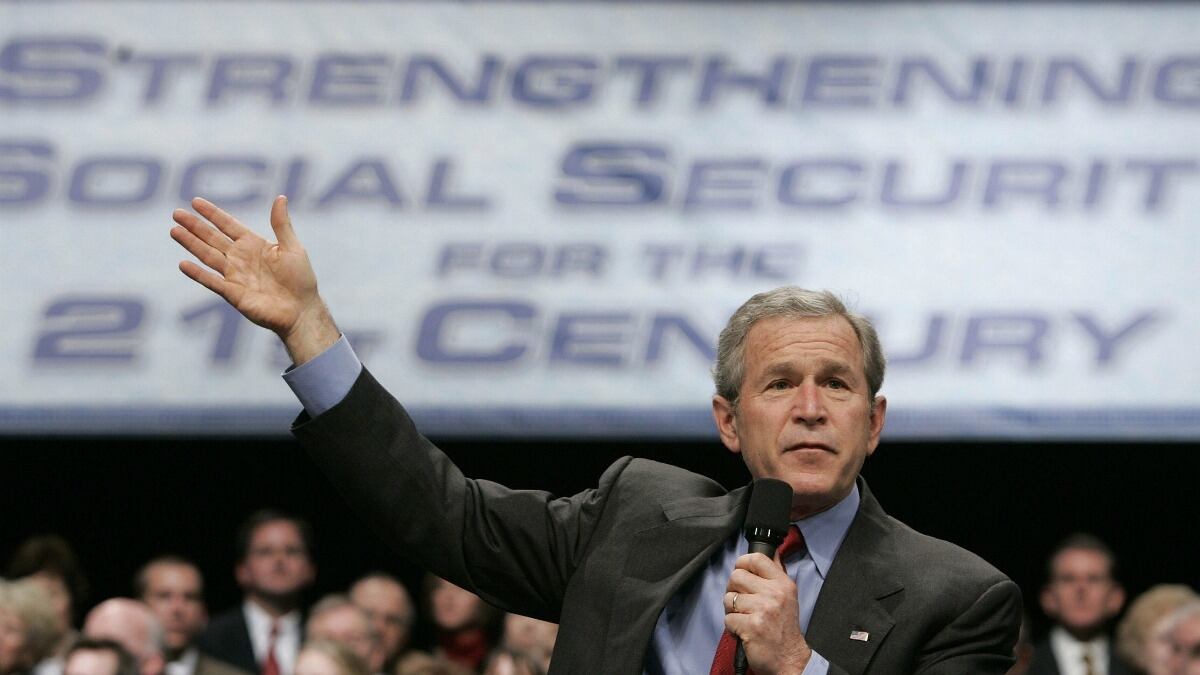

I think it's Philip Klein who is missing the point. Yes it's true, the cautious version of Social Security reform advanced by President Bush in his second term envisioned creating optional private accounts within Social Security, leaving in place most of the program and the existing Social Security tax mechanism.

But conservative policy types—like those at Cato—have long urged a much bolder move: direct investment by savers in retirement accounts that they would actually own, as a substitute for the current Social Security system.

Here is just one example of such urging, chosen more or less at random from hundreds of examples. It was written by Cato Vice President David Boaz back in 2005, at the zenith of Social Security reform advocacy:

Instead of paying taxes for 40 years and then hoping that Congress would raise taxes on the next generation to pay the promised benefits, workers would have their own money in their own account, an account that would belong to them. Within some limits, they could control how the money is invested, and how they withdraw it in retirement. And workers could leave the money they had saved to their children.

The clear idea here is that the account would be outside the Social Security system—i.e., that workers would be buying a private product, a retirement account. If the healthcare mandate is unconstitutional, however, so would be the dream of transforming Social Security into a system of privately owned personal accounts.

Yes, of course, Republicans could advocate abolishing Social Security, and then freeing workers to save their money or not in purely private accounts that would (or wouldn't) provide for their retirement. But that isn't much of a policy idea. The idea as it existed circa 2005 was that workers would be required to save, subsidized if need be, and thus moved away from dependency.

That concept—so long, so ardently, and so expensively advocated by so many conservatives and libertarians—is the one that conservatives have abruptly decided is unconstitutional.

POINT 2:

Klein adds:

And while I'm at it, I should also respond to another Frum post in which he argues that conservatives who think the health care law should be struck down are "unwitting advocates of single payer." His point being that if the government raised taxes to finance national health care it would pass constitutional muster even though it would represent a much larger expansion of government's role than Obamacare. Yes, that may be true, but it would also be a lot more politically difficult to pass single payer.

At the height of their power in 2009, Democrats had 258 House seats and 60 Senate seats—and yet they couldn't even raise single-payer as a serious option. A single-payer bill authored by Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., had just 87 co-sponsors. So, to make the bill more politically palatable, they passed an unconstitutional law that conscripts individuals into the health insurance market to correct in a distortion in the market caused by other Congressional actions. If Democrats want to start an honest debate as to whether Americans want a massive tax increase to pay for a full-fleged Canadian-style national health care system, I say, bring it on.

In other words: don't worry that we conservatives have backed ourselves into arguing that the only constitutionally permissible way to cover everyone is through a big-government program. Such programs are so unpopular that Americans will never vote for them! No worries, go for broke.

Except ... the U.S. has a massive Canadian-style national healthcare system, albeit one restricted to people over age 65. It's pretty popular too, so much so that polls consistently show that a plurality even of Republicans would prefer to raise taxes than to cut the program—which coincidentally even goes by the same name as the Canadian program, Medicare.

Klein and other Obamacare opponents want to force the choice that healthcare reform means Medicare or nothing, feeling very confident that Americans will forever and always choose "nothing," at least for the under 65s. I am not so confident.

On the other hand, maybe I shouldn't worry so much.

If the past three years have proven anything, they have proven that conservative principles are unexpectedly flexible. People who once championed the Heritage healthcare plan have renounced and reviled it—including its own authors! Jurists who once excoriated judicial activism now demand that judges revert to the hyper-activism of the 1920s and 1930s.

So perhaps I'm mistaken to believe that today's arguments for the unconstitutionality of Obamacare will somehow stop conservatives if the opportunity to reform Social Security does recur: those who have reversed themselves so radically once, are surely equal to the task of reversing themselves again.