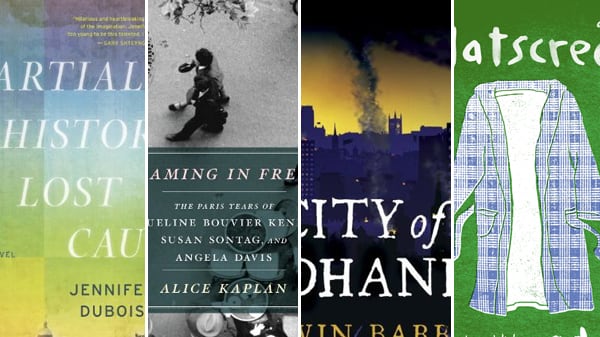

Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davisby Alice Kaplan

On the surface, Jackie Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis would seem to have very little in common, apart from fame and notoriety. But as Alice Kaplan shows in her new book Dreaming in French, they shared one thing which would determine the paths of each of their lives: they each studied in Paris at a formative moment in their youth.

Kaplan draws compelling and well-observed portraits of three extraordinary women as precocious youngsters, spending a year away from the American comforts of language, culture, and plumbing. Paris, sometimes lush and aristocratic, sometimes seedy and bohemian, allowed the trio to find the necessary distance from home to discover who they were.

In Paris, Kennedy wrote upon her return, “I learned not to be ashamed of a real hunger for knowledge, something I had always tried to hide.” Traveling throughout the country with her coterie of well-born friends and studying at the demanding Smith College program, Kennedy immersed herself in 17th and 18th century literature, especially the memoirs of the Duc de Saint-Simon. Kaplan calls her “a French time traveler.”

Kennedy’s insights into the court politics of Louis XIV later proved invaluable to her husband and his advisors on the campaign trail. However, JFK would eventually ask his wife to tone down the Frenchness. Congressmen who came to dine complained when they saw potage on the menu, and the country wanted to see her dressed by American, not French, designers. She solved this problem by patronizing the American but French-born couturier Oleg Cassini, who created her now-iconic brand of chic, and who rarely missed an opportunity to work in a subtle nod to French fashion.

By the time Sontag made it to Paris in 1957, the intellectual energy in Paris was already legendary. Sartre, Beauvoir, Vian and Greco were holding court in the cafes and nightclubs of Saint German. Barthes, Derrida, Foucault and Lacan were starting to develop the ideas that would revolutionize the humanities. After steeping in this environment for a year, Sontag became the high priestess of French avant-garde culture. She was aware of Barthes and company before nearly anyone else across the Atlantic, developing an “aura” thanks to “what she learned, then learned to transmit, from France.”

There were limits, however, to Sontag’s own “Frenchness.” Her first novel, The Benefactor, was deeply influenced by the Nouveau Roman, and was received in the U.S. as “the Great Un-American Novel.” When the book was reviewed in France, though, a reviewer declared: “Despite her French affinities, I’m bound to say that the hero of The Benefactor seems to me closer to those of Updike and James Purdy than to those of our ‘new novel.’” Too French for America and too American for France—such was the double bind in which each of these women invariably found themselves.

That her three subjects lived in Paris between 1949 and 1963 allows Kaplan to examine France and the U.S. in a crucial period in their histories. However critical the French were of race relations in America, their own society had been polarized by the Algerian War, and racism had become shockingly de rigueur. Richard Wright and James Baldwin had made France out to be a color-blind paradise. But Davis was appalled by the oppression of the Algerians she witnessed, and drew a trenchant comparison to what she had seen in her own home town. Writing about a pro-Algerian demonstration that took place in the place de la Sorbonne in July 1962, Davis noted, “When the flics broke it up with their high power water hoses, they were as vicious as the redneck cops in Birmingham who met the Freedom Riders with their dogs and horses.” When Davis later got involved in prison work back in the U.S., Jean Genet became one of her most stalwart allies, and when she was herself imprisoned and put on trial for kidnapping and murder, French intellectuals mobilized in her defense. Dreaming in French becomes not only the story of the role France played in the lives of these three women, but of the impact these three women would in turn have on France.

Dreaming in French is, above all, an attempt to validate an undervalued aspect of American culture: the study abroad narrative. The stories of girls overseas have not often been part of the canon of American expatriate writing, Kaplan points out. We have a wealth of material from Norman Mailer, George Plimpton, Saul Bellow, James Baldwin, et al, from their own days on the GI Bill, their Guggenheims, or their Fulbrights. Young American men in Paris were intent on “embrac[ing] irresponsibility,” as James Baldwin put it, producing work that is “gritty, irreverent, macho, [and] frequently alcoholic.” Their female peers, on the other hand, were determined “to embrace a new language and master a highly coded way of life.” Kaplan, a deft historian, avails herself of a range of sources in order to reconstruct their experiences, talking to their classmates and the families who housed them, reading their letters home, looking at the photos they and their friends took, watching the available footage of them speaking French, and reading the newspapers they would have read.

I was once a student at Columbia’s Reid Hall in Paris and a professor at New York University’s Paris campus—I can confirm that the experience of studying abroad marks you for life, forcing you to interrogate your identity as you reconstitute it in a foreign setting. You are not simply “translating” yourself into that language; you are building your identity within it. “True philosophy,” Kaplan quotes Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “means learning to see the world anew.” In their time in the City of Lights, Kennedy, Sontag and Davis didn’t just get an education. They acquired a worldview, and one that would leave an inarguable imprint on history.

—Lauren Elkin

A Partial History of Lost Causes by Jennifer DuBois

Jennifer DuBois’s debut novel opens with an epigraph from Vladimir Nabakov: “We are all doomed, but some of us are more doomed than others.” Perhaps an equally appropriate selection for this tender but sharp-edged book would have been the refrain of Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “One Art”: “The art of losing isn’t hard to master.” This is a story about learning to face loss and failure—if not with grace or composure, then at least with personal integrity.

Outside Boston, a college student named Irina learns she has inherited Huntington’s disease, the illness that has taken her father’s mind and is now, slowly, taking his life. Even as she goes on to finish a Ph.D., Irina falls into a muted despair. As it happens, she falls in love, too. But with the diagnosis hanging over her, she keeps commitment at bay, certain that her years of good health are numbered. What she really wants is a way to escape her own life, and in so doing, avoid replaying the slow, painful disintegration that eroded her father’s spirit in the years leading up to his death.

Meanwhile, in Russia, chess great Aleksandr Bezetov (whose story echoes Garry Kasparov’s) has discovered his second calling as a political activist. He embarks on a hopeless presidential campaign to make a statement against the government, dodging death threats and reevaluating his own ideals all the while. As he replays the political compromises he made to further his chess career in his youth, Aleksandr must calculate just how much he is willing to sacrifice now, so late in the game, in the name of his beliefs.

The novel’s chapters alternate between Irina’s and Aleksandr’s lives as they gradually converge. What brings this unlikely pair together is a device so well-constructed it hardly matters if it’s plausible. After her father’s death, Irina stumbles upon a strange loose end among her father’s papers: A copy of a letter he wrote to Aleksandr years before. “I feel a certain affinity with you, I suppose, because I’m fighting my own complicated match these days—and am, I fear, nearing the bitterest of losses,” the letter explains. “And I’m wondering if there’s a question you might find time to answer for me.” Irina’s father goes on to ask about the times when the champion chess player knew, as he was playing, that he will lose: “When you find yourself playing such a game or match or tournament, what is the proper way to proceed?”

Her father never got an answer. So Irina, with everything and nothing to lose, decides to seek one from Aleksandr in person. She dismantles her American life and lands in Russia; what ensues transforms them both. Irina’s sudden entrance into Aleksandr’s life forces him to reconsider the motives, decisions, and ghosts of his youth. For her part, Irina finds an answer, of sorts, to the question of how to live without a future.

The symmetry of its plot is one of this novel’s pleasures, but that’s not all A Partial History of Lost Causes has to offer. DuBois doesn’t let neat motifs and lofty metaphors overshadow Irina or Aleksandr’s individuality. It becomes increasingly clear just how different Irina and Aleksandr are from one another—and how distinct their particular battles are.

In the end, it is Irina’s story that carries the novel, largely because of the force of her personality. Aleksandr’s story is written in the third-person, but Irina’s chapters are in the first person. And for all her self-pitying and self-obsession, Irina’s voice possesses a quiet defiance and grim humor that is nothing short of charismatic. Her emotional life may be crippled by the knowledge that she has inherited a fatal degenerative disease—the plot, after all, revolves around her running away from her mother, her friends, her boyfriend, her home and her diagnosis. But Irina’s isolation only sharpens her perception of her predicament (“I’m both impious and clinically self-absorbed, so it makes sense that I look hardest for meaning in my own memories,” she explains.) When it becomes apparent that Aleksandr has no simple answer for her, it finally occurs to Irina that she may be able to formulate one herself.

There’s room to argue that everything is resolved too neatly for Irina and Aleksandr in the novel’s conclusion, but it’s hard to fault DuBois for wanting to grant her courageous, flailing characters some final respite from their accumulated tragedies. This is a book about the messiness of what it means to “scrape against the edges of your own self.”

—Mythili Rao

City of Bohaneby Kevin Barry

The good news, at least according to Kevin Barry’s debut novel, is that the world doesn’t end in 2012. It’s difficult, however, to dispute that something has happened between now and four decades hence, the time in which City of Bohane is set. The west of Ireland—once peopled with villages of harmless old twilled codgers—is now a barely habitable gangland. That is to say, Bohane is habitable so long as you stay on the right side of Logan Hartnett, its equal parts ruthless and fashionable boss. Alternately known as “The Long Fella” or “The Albino,” Hartnett rules the various factions of Bohane through guile, cunning, and a fondness for flashy threads. “He had that Back Trace look to him,” Barry writes, “a dapper buck in a natty-boy Crombie, the Crombie draped all casual-like over the shoulders of a pale grey Eyetie suit, mohair. Mouth of teeth on him like a vandalized graveyard but we all have our crosses. It was a pair of hand-stitched Portuguese boots that slapped his footfall, and the stress that fell, the emphasis, was money.” The sartorial choices of Bohane’s more prominent residents get a lot of attention from Barry, who, it should be noted, is rocking a slick porkpie and scarf in his author photo. But Logan and the Hartnett Fancy soon have bigger things to worry about than which pair of wingtips to lace up. That’s because the Gant, an old rival of Hartnett, has just returned to town after many years of exile.

Barry has created a pleasurably disreputable, mildly intoxicating future world full of checkered histories, colorful characters and visible scars. Besides Logan and the Gant—described as “half mad by the looks of things”—Bohane is home to up-and-coming gangsters like Wolfie Stanners, Fucker Burke, the beautiful, deadly and foul-mouthed Jenni Ching, a violent band of Caribbean-influenced “sand-pikeys,” and a nasty, Belfastian-level territorial rivalry between Logan and his less well-dressed cousins in the Northside Rises.

Barry’s denizens, unfortunately, are often as shallow as their wardrobes indicate. Logan, specifically, has the makings of a great literary creation, equal parts Ziggy Stardust, Bill the Butcher and Norman Bates. But Barry never satisfactorily fleshes him out. And it’s not just Logan that lacks for depth. Barry presents the entire city as an echo; he makes casual, deliberately vague mentions of pivotal events that have shaped the current, mostly sorry state of affairs. The reader is left to wonder: What were the exact circumstances of the Gant’s exile? What is the condition of the world beyond Bohane’s borders? (On a less crucial note, how does Jenni Ching get bloodstains out of her patented white leather jumpsuit?) Barry is in no hurry to clear up the matter. Whatever your opinion on his plot, it’s difficult to ignore Barry’s gift for language. Once you negotiate the basics of his invented slang, the dialogue is an absolute pleasure to read. There is a certain hypnotic rhythm, almost an improvisational quality, to his sentences. “When a reminiscence got going in the Back Trace, nights, it worked like a freestyle morphine jazz.”

The steampunk setting fits a writer of Barry’s talents and sensibilities. The bloodthirsty Young Turks of Bohane bide their time, waiting in the shadows to shank and supplant their revelry-addled elders. In Barry’s world, the cycle of life is a beautiful, deadly thing.

—Drew Toal

Flatscreenby Adam Wilson

It’s a hard time to be an American slacker. Tightening parental purse strings mean that a young man may no longer be free to languish in his childhood basement indefinitely. In his debut novel, Adam Wilson has diagnosed a form of modern suburban malaise that has so far gone untreated in literature.

Eli Schwartz, the novel’s first-person protagonist, is a slacker for the YouTube age. Paunchy, pale, and sexually frustrated (of course), but also wickedly intelligent and darkly comic (and a Whole Foods gourmand, to boot) Eli has spent his post-high-school years being steadily disabused of everything he thought he knew about how the world worked, while those less sensitive and intelligent of his classmates settled into the upper-middle class career tracks of their parents. The Boston suburb from which he can’t escape is populated with ghosts of his high school past; either those who flaunt their upcoming and inevitable success, or those who, like Eli and Bartleby, decided that they’d prefer not to.

The man who’s purchasing Eli’s mother’s house (thereby displacing Eli from his natural slacker wetland habitat) is Seymour Kahn, aging and paraplegic former star of the small-screen. Seymour is a projection of Eli’s id as it would wish to be; where Eli’s unwilling nihilism causes him to withdraw, Kahn’s nihilism (just as strong) fuels his Dionysian hunger for sex, drugs, and general debasement. An odd friendship is struck up, based initially on a shared passion for altered states, and together they make up two halves of one manic-depressive. Minor characters and misadventures revolve around the two of them, but the real power of this book comes from their relationship, which is as much co-dependent as it is, in an awkward and unspoken way, nourishing.

Eli fancies himself a bong-wielding Holden Caulfield in a bathrobe. He yearns to feel something, even though he is well aware that the idea of “yearning to feel something” has been artistically strip-mined, and his self-medication is an attempt to cure his acute case of cultural trope exhaustion. Naturally, it doesn’t work well; with still a third of the book remaining, he begins to give the reader “possible endings” to his story, as they might occur in the various forms of modern storytelling in which he has drenched himself. This dilemma, that all possible endings are already implied with the premise, expands into the larger question that hangs over the bleak narrative: What is left for you when the preceding generation has already claimed “Whatever” as their mantra and ethos? Where do we turn when even the question of authenticity rings inauthentic? Can anything be really real anymore?

Wilson’s prose is original and arresting, and although there’s a break-in period with his propensity for subject-less verbs that’s almost as taxing as the invented vocabulary of A Clockwork Orange, he approaches, in his loftier moments, the tortured grace of George Saunders. This is Cheever on Xanax, or maybe lithium, but the voice is still there; sardonic, hilarious, and very much of our time. Wilson is a writer to watch.

—Nicholas Mancusi