Red Brick, Black Mountain, White Clay

Christopher Benfey might seem ensconced in the traditional style of cultural criticism celebrated in The New York Review of Books, but his new book—memoir? History? Art criticism?—is something entirely different.

To understand the sort of unclassifiable book the cultural critic Christopher Benfey has written, begin with the Library of Congress’s description on the book’s copyright page: “1. Art and society—United States—History. 2. Benfey, Christopher E.G., 1954—Family. 3. Artisans—United States—Biography.” That’s a bare skeleton, but even that sketch gives you some notion of this strange but beguiling work’s genre-busting qualities. Mixing memoir, family history, art history, and biographical portraits of American artists, craftspeople, and naturalists, Red Brick, Black Mountain, White Clay is a book like no other, and therein lies its many charms and its occasional frustrations.

In the opening pages, Benfey writes, “I am searching in this book for a pattern in the wanderings of my far-flung family. But the narrative has more to do with geology than genealogy. I take my promptings from the material order of things, and especially from the clay—whether the dark, iron-rich clay of red brick or the white clay of Cherokee pottery and fine porcelain—that is a recurring motif in the book. My own memories take up relatively little space.” He goes on to say, “The first section evokes the red-clay world in rural North Carolina,” the homeland of his mother, the Quaker daughter and granddaughter of bricklayers and brick-makers. “The second section moves west into the Appalachian foothills, to the visionary experiment in education and the arts undertaken at Black Mountain College,” which was run for many years under the direction of the artist Josef Albers, whose wife, Anni, was the author’s great-aunt. “The third section moves farther west and further back in time, as I tell the extraordinary story of the eighteenth quest for ‘Cherokee clay.’”

Along the way we encounter the North Carolina folk potters of Jugtown, that state’s small but durable Quaker tradition, the painter James McNeil Whistler, the German folklorist Theodore Benfey, and the great American naturalist William Bartram (also a distant Benfey relation). Like a wanderer in one of those old 19th-century museums that were more oddball collections than neat classifications, Benfey takes his cue from Josef and Anni Albers, who were keen on ancient patterns of design as found in pottery or weaving, particularly “one of the oldest in human history, known as the meander or Greek key.” As it has come down to us “on the borders of pottery and textiles, the meander resembles a maze or labyrinth.” The English potter and ceramist Josiah Wedgwood loved the meander. And so does Benfey.

Like a shy, eccentric curator of his own family museum, the author mostly stays in the background and lets you make what you will of the strange stories and facts he’s assembled. Only near the end does he step fully into the light for one brief occasion to say—sort of—what he’s up to. With his mother dying in a North Carolina retirement home, he goes back and forth between a description of her decline and a meditation on Whistler’s painting Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, more familiarly known as Whistler’s Mother (the connection here: like the author’s mother, Whistler’s mother was born in North Carolina, in Wilmington, where Benfey’s mother often dreamed of living, walking in the sand on Wrightsville Beach, and eating freshly caught fish). “As I try to satisfy my own curiosity about this marvelous painting, I think I know what’s really happening here. My own confused feelings while sitting with my mother in her residential wing in Friends Homes have started to grow, like a gently spreading moss, onto Whistler’s portrait of his mother. Everything about the painting recalls aspects of my mother, and everything about my mother takes up residence in different aspects of the painting. Whistler’s portrait of his mother is the culture on which I am growing my own memories of my mother. Is this a defense mechanism, a way of not quite looking at what my mother has become? Of course it is. But it’s also a way—my way—of looking at her.”

I want to call this book a memoir, not because I want to simplify it or reduce its scope, but because I think the hope and promise of that ruleless genre are embodied in books like this one. Time and again, Benfey risks getting lost (sometimes literally: he misplaces the North Carolina city Winston-Salem in Randolph County, not Forsyth), but his wandering ways usually pay off. The result is a strange history of American craft and art—a tradition that literally has its roots in the very earth of the country—that begins in the personal and winds up in a much more universal sphere. Red Clay, Black Mountain, White Clay provides a new and useful way to examine American culture, where it’s been, and where it might go. Call it what you will, but you can’t ask more of a book than that.

—Malcolm Jones

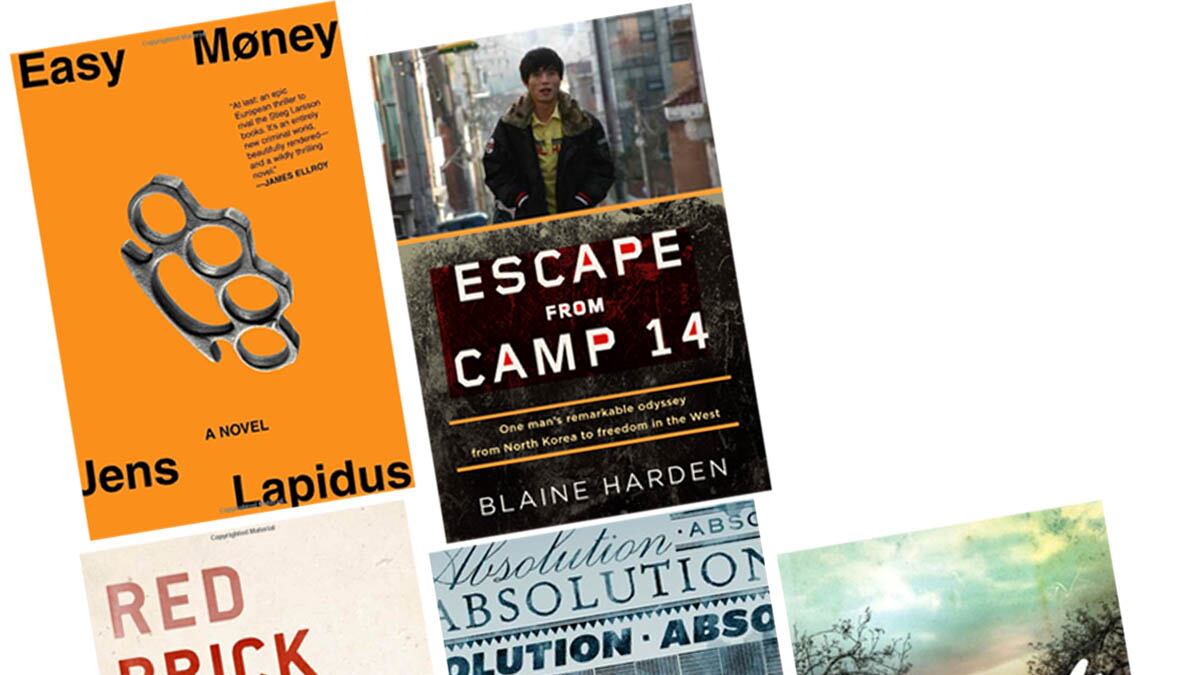

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo 2.0? Swedish criminal defense lawyer Jens Lapidus’s thriller debut skillfully delivers on action.

From one of the most successful criminal defense lawyers in Sweden, that new cradle of crime fiction, comes Easy Money, an intelligent and original thriller that displays as much wit as it does muscle. First-time author Jens Lapidus skillfully weaves together the narratives of characters from every level of the Swedish criminal underworld, including a cab-driving drug runner looking to climb the ladder to support his own party habit, a massive roid-raging enforcer who lives for the thrill of violence, and the Yugoslavian crime lord who’s pulling the strings.

Fans of a certain girl with a certain tattoo will find plenty to love here; Lapidus is a fantastic writer of action, but he also knows when to leave the guns holstered and build suspense. A deft translation by Astri von Arbin Ahlander means that all the slang and criminal parlance will ring authentic for an American audience while still maintaining a European flair. The reader gets the sense that Lapidus must have drawn heavily from his experience with his clients—perhaps not the wisest move from a legal standpoint, but it makes for great reading.

Escape From Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey From North Korea to Freedom in the West

Imagine being born inside a political prison camp, and that was the only life you knew. That was the world that North Korean Shin Dong-hyuk was raised in, until he fled. Veteran reporter Blaine Harden tells it like The Great Escape.

With all of the geopolitical bluster surrounding North Korea, especially of late, it can be forgotten in the noise of leadership changes and missile launches that one of the Hermit Kingdom’s most pressing crises is a simple one: roughly 200,000 North Koreans are held in political prison camps under monstrous and inhumane conditions, where they are worked to death and more or less oblivious to the external world. In this important book, veteran reporter Blaine Harden tells the story of Shin Dong-hyuk, the only known person born in one of the camps to successfully escape.

The book works on three levels. As an action story, the tale of Shin’s breakout and flight is pure The Great Escape, full of feats of desperate bravery and miraculous good luck. As a human story it is gut wrenching; if what he was made to endure, especially that he was forced to view his own family merely as competitors for food, was written in a movie script, you would think the writer was overreaching. But perhaps most important is the light the book shines on an under-discussed issue, an issue on which the West may one day be called into account for its inactivity.

In his debut novel, emerging talent Patrick Flanery explores art’s responsibility to truth during times of unrest, with South Africa’s apartheid as the motivating evil.

South Africa has in many ways stood as an odd kind of political cousin to America, and uncomfortable comparisons are unavoidable, especially in regards to how both nations struggle with the ghosts of their racist pasts (and, it’s argued, presents). In his debut novel Absolution, emerging talent Patrick Flanery explores art’s responsibility to truth during times of unrest, with apartheid as the motivating evil. Taking as its frame a series of interviews of famed South African author Clare Wald with her biographer Sam Leroux, the novel plays with time and perspective to slowly reveal that the two may be connected through Wald’s daughter, who disappeared at the height of the anti-apartheid movement.

Flanery is a talented prose stylist, and he deserves comparison to big names like Philip Roth and Margaret Atwood. This is a complex and ambitious novel in a grand tradition that dares to ask questions about censorship, memory, and political responsibility, all while maintaining a very human story of loss and forgiveness at its core. South Africa and its many familiar contradictions have gone underrepresented in American literature, but this impressive book will go a long way toward amending that deficit.

A wonderfully twisted novel about a young man who thinks too much about the meaning of life; all the while family members are going mad.

It may be true that the unexamined life is not worth living, but too much philosophy can have negative ends of its own. In Dirt, the third novel from internationally acclaimed David Vann (Legend of a Suicide, Caribou Island), 22-year-old Galen, steeped in new-age thought and desperate for some kind of transcendence, turns to philosophy as anodyne against what he sees as his dysfunctional family’s toils in samsara. His grandmother is slipping into senility, his father is out of the picture, his mother dotes on him in a way that edges uncomfortably close to Oedipal, and his aunt and cousin are moving in on his inheritance. When the family attempts to revive some fellow-feeling with a weekend at a secluded cabin, they careen into weirder and weirder territory, and Galen finds out how far he is willing to chase his need for meaning.

Vann uncoils the plot with wicked suspense, and is an excellent translator of Galen’s karmic torment and existential angst. The book is wonderfully twisted, but a sinister humor keeps things from getting too bleak. What begins as a literary family drama turns slowly into a heady horror story, part Stephen King and part Immanuel Kant.