Today, the Knesset held a special session on the proposed Judiciary legislation would formally codify the Israeli judiciary's ability to declare laws unconstitutional—and enable the Knesset the ability to override those same judicial rulings should 65 members (out of 120) so choose.

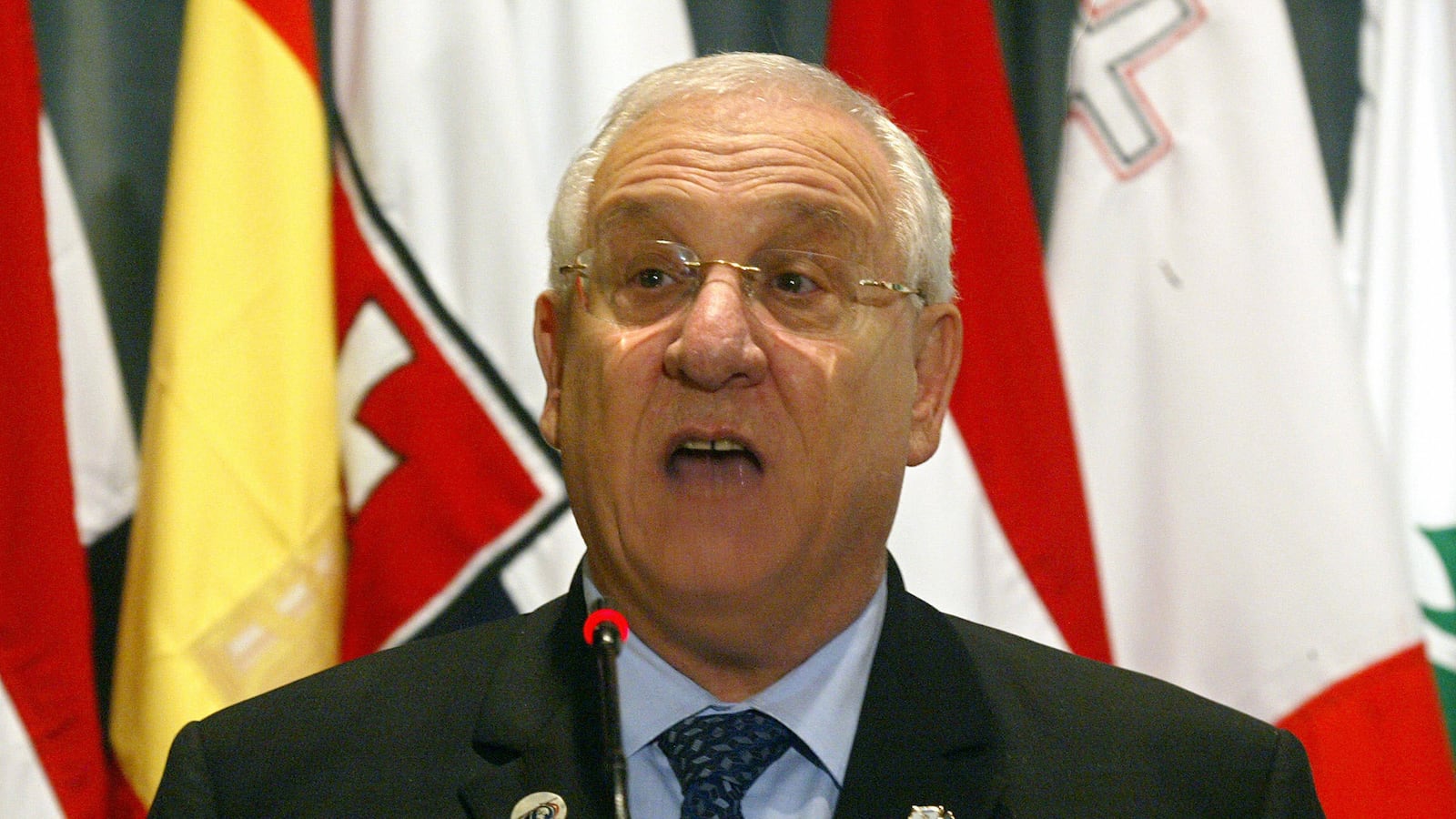

Knesset Speaker Reuven (Ruby) Rivlin is making waves with his support for this new legislation. Rivlin is a veteran member of the Likud old guard (along with Dan Meridor, Michael Eitan and Benny Begin) who, rightist politics notwithstanding, are classic Liberals and staunch defenders of the judiciary, as was their mentor, Menachem Begin, and his, Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Through last year, they steadfastly criticized the raft of bills put forth by younger Likud MKs, trimming speech and associational freedoms. Is Rivlin changing sides?

Not necessarily; some of Israel's leading activists support the new law.

But more importantly, the vicissitudes of Israel's judiciary illustrate a ongoing crisis of the Israeli left and center, one which American liberals may find sadly familiar, with no easy answers on either side of the pond.

As expertly traced by Menachem Mautner of Tel Aviv University in a volume published last year, Law and the Culture of Israel, in Israel's early decades, the judiciary, trained in British and German legal formalism, stuck to statutory interpretation, precedents, and strict adherence to separation of powers.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of judicial activism, value-driven jurisprudence and a new judicial self-confidence, responding to the weakness of the executive and Knesset (in war, hyperinflation), the emergence of mutually paralyzing left and right blocs—and driven by the most important internal Israeli story of the last decades, the decline of Labor and the party that carried its banner ever since the 1930s, Mapai.

It is hard to overstate Mapai's centrality to Israel's history. Its socialist Zionism provided centralized state-building, liberal politics, a moralist secular religion, and socio-economic solidarity to soften the harder edges of nationalism. It ran the Knesset, government, military, unions, much of the press and academia, and the judiciary had its back.

Like all ideologies Mapai pushed others to the periphery—Revisionists, the traditionally religious, and the masses of Sephardi immigrants. Since 1977, empowered by Likud's ascendance, they've all come around to collect, while the Labor ethos and secular liberalism have steadily declined on all fronts. As an astute blogger, Shalom Boguslavsky, has pointed out, Begin took the high road, and consistently chose not to inflict on his ideological foes the forced marginalization that Mapai had inflicted on him. Today's new generation of Likudniks, who knew not Begin, want to rule as thoroughly and hegemonically as did Mapai.

In the long, slow death of Mapai, the courts became the guardian of secular liberalism, and its profound cultural anxieties. Central here was Justice Aharon Barak, the phenomenally gifted jurist who worked full-blown constitutionalism and judicial review out of administrative law and key legislation from 1992 that enshrined "human dignity and liberty" as "the values of…a Jewish and democratic state." Barak steadily upheld the basic prerogatives of the state while thwarting the excesses of the religious parties and security establishments, and curbing the worst of the occupation, seeing the court, with some reason, as the last ditch, defending liberal values and saving the Jewish state from itself.

The courts, like the liberal elites they represent, have grown alienated from the body politic, for two reasons above all: The stunningly insular process by which judges have appointed one another; and Barak's far-reaching assertion of judicial supremacy, summed up in his programmatic statement: "Everything is justiciable."

This last doctrine interestingly parallels the "pan-halakhism" that has taken hold in Orthodox Judaism in recent decades, the assertion of rabbinic authority over every aspect of life and the displacement of responsive tradition with dogmatic traditionalism. In both cases, the law, dislodged from the larger socio-cultural frameworks that held it, is the last tool available to elites no longer sure of themselves in times of bewildering change.

Another resemblance—to American liberalism—is hard to miss. (And not only because both Barak and his chief debating partner, Professor Ruth Gavison, have long associations with Yale Law School, each internalizing one pole of the debate that has roiled American law for decades.) In both cases liberal elites have used courts to advance the values they saw being swept away in the rough tides of democratic politics—and paid for their failure to gain political and cultural traction with the delegitimization and takeover of the judiciary.

Liberalism—be it in America, Israel or within Judaism—will endure only by forging meaningful and convincing connections with the cultural values and concrete interests of the societies it aspires to shape. Overwrought legalism is a sign of alienation, from history and culture, from subtler forms of consensus and authority, and of people from one another. Neither liberalism, nor Judaism, can survive without law, but neither can they survive without striking deeper roots than the law can provide.