The so-called Latin Boom of the Seventies brought some to prominence: Julio Cortázar (Argentina), Carlos Fuentes (Mexico), Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru), and Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia), as well older masters like Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina), Pablo Neruda (Chile), and Octavio Paz (Mexico). But if there have been rebirths in the interest in Latin American literature since then, you and I probably missed them. It’s a sad state of affairs that books in translation account for only about 3 percent of titles published in the U.S.

The one exception has been Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño, who has single-handedly sparked his own boom with the posthumous publication of everything he ever scribbled, including such masterpieces as Distant Star, The Savage Detectives, and 2666. Last summer came Between Parentheses: Essays, Articles and Speeches, 1998-2003. The autumn saw the release of the 1989 novel, The Third Reich, and a collection of poems, Tres. And now spring is upon us—surely there is another Bolaño flowering. Lo! Out comes the short story collection The Secret of Evil.

Interestingly, Bolaño’s immense popularity and the huge growth in America's Spanish-speaking population have not fueled a contemporary boom.

That, however, doesn’t mean there is an insufficiency of good literature coming from Spanish-speaking Americans both North and South.

East Los Angeles writer Luis J. Rodriguez’s oddly hopeful memoir, It Calls You Back: An Odyssey Through Love, Addiction, Revolutions, and Healing, extends the scope of his classic gang-life account Always Running—he returns to the conflicts that he faced growing up, watching his son tragically ensnared by the same dark forces of el barrio.

Son of Guatemalan immigrants Héctor Tobar, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The L.A. Times, follows his debut The Tattooed Soldier with a sprawling social novel, The Barbarian Nurseries, which depicts Los Angeles in a way reminiscent of T.C. Boyle's The Tortilla Curtain and Joel Schumacher’s harrowing film, Falling Down. After a marital spat in the Thompson–Torres household, live-in Mexican immigrant maid Areceli finds herself alone in an empty house—except for the family’s two young sons. She tries to find the boys’ grandfather, and in the process, provides a vivid and entertaining parable of life in contemporary Southern California, replete with a wide swath of immigrants, politicians, vigilantes, and yuppies.

Salvadoran Horacio Castellanos Moya’s most recent novel Tyrant Memory, translated by Karen Silver, is based on real events: a failed 1944 military coup against El Salvador’s Nazi-loving Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, and a general strike that successfully ousted the dictator. Three points of view are expressed: a housewife’s diary, a picaresque recounting of the failed coup, and the ruminations of Pericles, an upper-class apparatchik, who years later makes good on a jailhouse prophecy. The novel’s epilogue makes clear, as we now know, the fleeting nature of El Salvador’s democratic moment.

The Secret History of Costaguana is Colombian Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s second novel to reach these shores. (The first, The Informers, was selected in Colombia as one of the most important works of the last 25 years.) His new opus imagines narrator Jose Altamirano’s relationship with the writer Joseph Conrad and how he deals with Conrad’s expropriation of Altamirano’s intimate revelations to create his novel Nostromo. The narration begins on the day of Conrad’s death, and moves from the turn of the century Central America, to Colombia, England, and back, even to Conrad’s fictitious South American nation, Costaguana. Vasquez has performed an admirable feat, building this fiction on the foundations of another novel, and appending a judicious dose of dark humor that blunts the impact of the horrors revealed.

Puerto Rican Esmeralda Santiago’s recent novel Conquistadora fictionalizes the life of 19th-century Jamaican sugar-plantation owner Annie Palmer (also immortalized in a 1929 novel White Witch of Rosehall). She places her unconventional and many faceted heroine in Puerto Rico, vividly portraying the mid-19th-century cholera epidemic that devastated that beautiful island, as well as giving voice to the secret abolitionist societies active in San Juan. (Puerto Rico was one of the last bastions of slavery in this hemisphere.) Santiago has written an account of the intertwining history of empire and sugar.

The Argentine-Chilean novelist Ariel Dorfman, who teaches at Duke University, continues the personal tale he took up in his first memoir Heading South, Looking North (also told in the documentary A Promise to the Dead) in Feeding in Dreams: Confessions of an Unrepentant Exile. The former ended with the military coup that overthrew President Salvatore Allende. The latter traces his exile to Argentina, where he fled death squads, and then sought sanctuary in Paris and Amsterdam, then has a brief and uneasy return to Chile, post-Pinochet. Feeding in Dreams is a panoramic and poignant personal retelling of recent political history viewed through a prism of conflicting emotions.

It is a different Chilean, Alejandro Zambra, who has been anointed the greatest writer of the younger generation, on the evidence of two minimalist novels Bonsai and The Private Lives of Trees, the first translated by Carolina De Robertis and the latter by Megan McDowell. Private Lives has Julian, a young literature professor, improvising bedtime stories (about trees) to his young stepdaughter, before he works on his novel (about a man nurturing his bonsai tree). His literary efforts dovetail with personal fears—he thinks about whether his child will like his novel when she grows up, and waits for his wife Veronica, who’s left them and never returns.

Argentine Luisa Valenzuela’s Dark Desires and the Others covers the 10 years she spent in New York, and has finally been translated into English by Susan Clark. It bends genres and piles on the candidness, as the author states at the very outset:

This is not an autobiography, nor are these my memoirs; they are simply movements of the heart and body tending toward the horizontal in more ways than one, and prone to various shocks.

Personal texts, never thought of as being written for anyone else’s eyes, notes in the margin of what some would call life and which nonetheless I feel to be themselves facts of the purest, rawest substance.

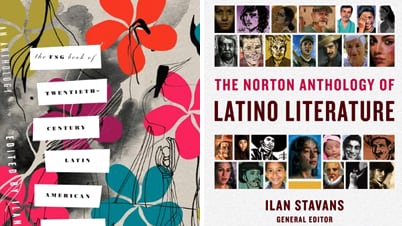

The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature and The FSG Book of Twentieth Century Poetry are two doorstop compendia edited by the go-to Latino scholar Ilan Stavans of Amherst College. The poetry anthology includes well-known figures such as Neruda, Paz, José Martí and César Vallejo, as well as a host of lesser-knowns. Surprisingly, it contains no work by, among others, the wonderful Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas (whose extraordinary autobiography Before Night Falls was turned into a gorgeous Julian Schnabel film) or the celebrated Chicana Sandra Cisneros, who wrote the charming The House on Mango Street. Stavans’s Norton edition extends from the earliest days of the New World (Bartolomé de las Casas) to contemporaries (Cuban Cristina García and Peruvian Daniel Alarcón), and provides useful and valuable bibliographical and biographical information. The strength of these thick surveys ought to remind us that there are many other fantastic writers out there, as great as Bolaño was.