In France the book was dubbed a polemic against motherhood—an outdated, out-of-touch, archaeo-feminist screed that drew so much ire from public intellectuals, it became a bestseller in the process.

“She is completely wrong,” Cécile Duflot, the head of France’s Green Party, said of the book’s author, feminist philosopher Elisabeth Badinter.

She knows “very little about ... today’s young mothers,” said Edwige Antier, a prominent pediatrician and government legislator.

Other labels spewed at the author, known as one of France’s foremost intellectuals: “bad mother,” “shortsighted,” “faux feminist.” All as the motherhood manifesto continued to fly off shelves.

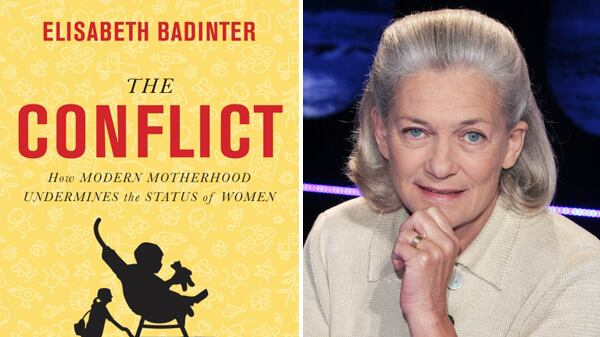

At issue was Le Conflit: La Femme et la Mère—The Conflict: The Woman and the Mother—a vehement polemic against the over-parenting tactics of a new generation of young mothers, which Badinter argued were holding women back. Released in France in 2010—but entering the U.S. market only now—the book loudly proclaimed that French mothers, with their tax breaks, paid maternity leave, and laissez-faire approach to parenting, were suddenly at risk of turning into what were essentially Park Slope mommy tyrants (though she didn’t call them that). They were coddling, co-sleeping, obsessing about organic diapers, breast-feeding into the toddler years—and in the process, tethering themselves to the home in a way not seen since the 1950s.

“The baby,” Badinter wrote, “is the best ally of masculine domination.”

They were harsh words at the time, coming from a mother of three grown bébés—but they are surely no less surprising now, particularly amid enough American mommy controversy to fill parenting books for decades. Though Badinter claims she doesn’t “know enough” about American mothers to comment on them specifically—and so the translation of her book, now called The Conflict: How Modern Motherhood Undermines the Status of Women, remains focused largely on the French—controversy is perhaps what the 68-year-old grandmother does best. Her first book, written when she was 35, argued that maternal instinct was a cultural construct. More recently, the protégé of Simone de Beauvoir has blamed feminists for inventing the concept of “victimization” and lobbied in support of the so-called burqa ban.

“I get a great deal of pleasure in expressing ideas ... that go against the current,” the philosopher told The New Yorker in a profile last year, shortly after being voted her country’s “most influential intellectual” by a French weekly. “I love to throw out a contrary point of view, and I do it with, perhaps, a certain lack of subtlety.”

In The Conflict, what’s clear is that Badinter believes modern motherhood—what we might call good old-fashioned helicopter parenting—is holding women back (and that there are plenty of American influences that have played a role in the process). Which might come as a surprise, given that we all just learned, in the incessant coverage of Bringing Up Bébé, how happy and well-adjusted French mothers (and their children) seem to be. But the problem, says Badinter, is how those values have changed—morphing into a style of mothering she calls “crushing.” You know, the kind of women who give birth without an epidural for the “natural” experience; who sleep with their children to enhance the mother-child bond; who feed only organic, use only washable diapers, and who breast-feed—even when they may prefer not to—because it’s the “right” thing to do.

It’s environmentally friendly, sure—but it’s also a hell of a lot more work. (Powdered milk, jars of baby food, and disposable diapers were created for a reason, says Badinter.) But the less modern women use them, the longer they stay at home, bending over backward for their children, losing a sense of independence—and economic edge—in the process. “We used to talk constantly about ways to reconcile a woman’s maternal responsibilities with her need to retain financial independence,” Badinter tells The Daily Beast by email. “Now we talk exclusively about a mother’s duties and the ‘rights’ of the young child, which increase substantially year after year.”

Badinter does not place the blame solely on any institution, but a combination of forces. Among them: the successive economic crises of the last 20 years, in which some women decided, as Badinter puts it, that it was better to be a “perfect mother” than manage the stress of work and home (and the frustration of the “inevitable glass ceiling”); the resurgence of “naturalist ideology” (read: the organic revolution), in which women turned down painkillers and even birth-control pills and slaved away in the kitchen puréeing organic broccoli. And then there is the group with which Badinter takes special issue: the American-born La Leche League, whose crusade to bring back breast-feeding, started in a Chicago-area living room in the 1950s, has, she says, successfully spread throughout the Western world.

“Today a mother who has just given birth is ideally supposed to display all the reflexes—some use the word ‘instinct’—of a female mammal,” Badinter says. “She must immediately forget about herself and her personal desires in order to be available 24/7 for months on end to minister to her child’s every need. Day and night for six months, breast-feeding exclusively, followed by mixed feeding with organic products lovingly prepared by the mother. This keeps her at home, tending her baby, which is not necessarily every woman’s idea of heaven.”

The problem with Badinter’s argument is that it’s not every woman’s idea of hell, either—particularly here, where most women don’t have the luxury of staying home. French law provides tax breaks and extended maternity leave for new parents. U.S. law does not. French women are literally offered state-paid extended courses of vaginal gymnastics—to get them back in shape. American women are not. French women get an extra six months off if they choose to breast-feed—and yet, the French still have one of the lowest breast-feeding rates in the world. Moreover: what does Badinter think is so hard about washing an organic diaper, anyway? France still has more working women than any other country in the European Union—a figure roughly equivalent to that of the United States.

So the question, for American readers, anyway, may be: what exactly is the problem with modern mothers?

Yet, whether Badinter is out of touch as an author likely goes back to whether she’s out of touch as a mother. And while she’s portrayed herself as an ordinary mom—she had three children within three and a half years, all while a full-time student—she also had an au pair to help out. Her family wealth is estimated at $920 million. Her husband, Robert Badinter, is a former French justice minister and a prominent lawyer.

Still, Badinter contends, no mother is perfect, least of all she. “The more time passes, the more I’m convinced that the perfect mother is a myth,” she says. “What woman can boast of having always had the right reactions, made the right decisions? … As for me, I’ll say that it’s for my children to judge.”