Consumerism: the Purest Kind of Politics

On Black Friday last year, shoppers in an Arkansas Walmart rioted over a $2 waffle iron. You must understand: supplies were limited. The year before, police arrested a woman at a Toys “R” Us Black Friday sale in Madison, Wisconsin, after she cut other shoppers in line and threatened to shoot them. Dozens of similar incidents have been reported in recent years. They’ve become as reliable as the extended queues outside Apple stores before the release of a new iPhone or iPad. Consumerism is America’s great religion, and these are the actions of its disciples.

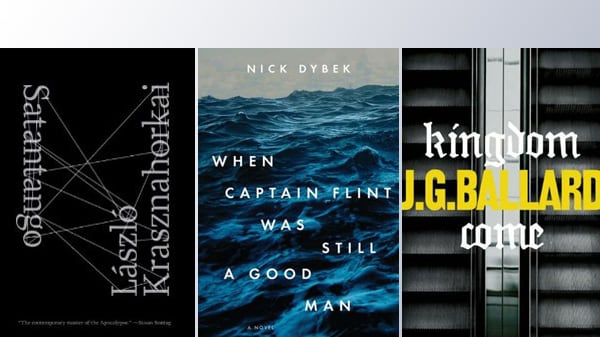

These sorts of incidents wouldn’t be out of place in Kingdom Come, a posthumous novel by the great British writer J.G. Ballard. In the book’s canted world, consumerism has subsumed the vast suburbs extending out from London and Heathrow airport. (“This isn’t a suburb of London,” one character instructs. “It’s a suburb of Heathrow and the M25,” the enormous, congested motorway encircling London.)

The town of Brooklands is dominated by the Metro-Centre, an enormous, domed shopping mall; townspeople refer to it—sometimes derisively, but often rapturously—as a cathedral. “The town was an end state of consumerism,” Ballard writes. “They lived in an eternal retail present, where the deepest moral decisions concerned the purchase of a refrigerator or washing machine.” There is an aura of transcendence, a spiritual fulfillment that comes with attaining “an intense transactional present.”

But the consumerism of Ballard’s world isn’t just a shallow commercialism, a worship of Gucci and gadgetry. Rather, it masks—or perhaps abets—a growing intolerance and discontent among the people of Brooklands. Attacks against immigrants and minorities are becoming commonplace. Gangs of men prowl around town in shirts bearing the St. George’s Cross, the use of which in recent years has been linked to some far-right nationalist groups, like the xenophobic British National Party. The violence is dismissed as the work of football hooligans—the Metro-Centre is associated with clubs of jingoistic sports fans—but one day, an unknown gunman opens fire in the Metro-Centre, killing several shoppers.

The shooting is the inciting event of Kingdom Come, and it brings to town Richard Pearson, a 42-year-old, recently sacked ad executive. Pearson’s father, a former airline pilot and possible right-wing sympathizer, was among the dead, and though he hadn’t spoken to him in years, Richard sticks around and begins investigating the crime.

For years Ballard wrote speculative fiction, and he has the sci-fi writer’s commitment to his conceits. The Metro-Centre and the shopping culture of Kingdom Come are not idly drawn metaphors; rather, they have helped to create a fully dystopian society, one whose figurehead is David Cruise, a telegenic former B-list actor who stars on the Metro-Centre’s in-house television channel. There he exhorts shoppers to buy more, to obtain membership cards and benefits that serve as a veritable surrogate for citizenship. He also promotes the sports teams who work in concert with the Metro-Centre. He is the talk show host as secular prophet—Oprah with an unstable, quasi-political constituency.

Ballard guides us through this unsettling environment, an exaggerated version of modern Britain, with a sure hand. His sentences, almost anthropological in tone, indicate a boiling over of tension: “The suburbs dream of violence. Asleep in their drowsy villas, sheltered by benevolent shopping malls, they wait patiently for the nightmares that will wake them into a more passionate world.”

The description comes from Richard, who has the jaded ad executive’s cynicism about human behavior. It imbues his narrative with a weary omniscience. He sees the Thames Valley, which encompasses Brooklands and other similar towns, as “a terrain of inter-urban sprawl” with “few signs of permanent human settlement.” It’s only natural that he’d later get involved with David Cruise, serving as his media adviser; this is Richard’s type of sandbox.

We learn early on that there’s some sort of conspiracy at the heart of Kingdom Come. The man arrested for shooting Richard’s father and several others at the Metro-Centre is quickly released, his alibi coming from several people who seem suspiciously connected to one another. There are questions about the role the Metro-Centre is playing in attacks on minorities. It seems as if “a soft fascism” is taking over the town, a blend of hyper-consumerism and rabid football nationalism.

It’s a peculiar mix at times, and Richard is a bit too hollow as a character (we learn frustratingly little about his earlier relationship with his father or his own forsaken life in London). But Ballard’s work is so pleasurable to read, sentence-by-sentence, that it’s easy to float along. It’s filled with so many quotable satirical bits, satisfying aperçus of pop psychology and fractious jabs at late capitalism, that whole pages of my copy were drenched in blue ink.

“Like it or not, only consumerism can hold a modern society together,” says one conspirator. “It presses the right emotional buttons.”

When a mob gathers, a police superintendent surveys “the riot with the calm gaze of landowners observing their tenants at play, as if burning cars and racial brawls were boisterous recreations that suited the brutal peasantry of the motorway towns.”

What Ballard has done here is to emphasize this society’s psychogeography over its people: “It’s a new kind of consumerism—sponsored football teams, supporters’ clubs, marching bands, stadium lights blazing all night, cable TV.” This is a novel about crowds—Don DeLillo would tip his hat in recognition—and the economic and social conditions that can be used to manipulate them. If the characters in Kingdom Come seem indistinct by comparison; if David Cruise doesn’t quite seem worthy of “the pale aura of suburban fame” that surrounds him—well, perhaps it’s because from this remove, it’s difficult to understand why people would launch into a melee over a waffle iron or camp out for a cell phone. But these things do happen, every year, and Ballard’s novel is at its best when it takes this behavior to its most frightening, but strangely possible, extremes.

—Jacob Silverman

Trouble is brewing on Loyalty Island. John Gaunt, president of Loyalty Fishing, lies on his deathbed, his son Richard poised to inherit all. Rumors circulate that Richard may sell the entire fishing fleet to the Japanese. Cal’s father and his colleagues depend on those six-month trips to Alaska to keep their families afloat. When their fears are realized and the island looks likely to “shrivel and die” the seamen are driven to drastic measures. A suspicious Cal soon discovers his father was complicit in taking Richard out to sea and throwing him overboard. Nick Dybek depicts Cal’s internal struggle to keep this dark secret and reconcile this new, altered image of his father with that of the idealized version he once cherished.

When Captain Flint Was Still a Good Man follows the familiar pattern of many a debut: a first-person narrator coming-of-age bildungsroman with a smattering of literary references to enrich the text and validate the writer’s credentials. But Dybek’s novel succeeds in being a cut above most debuts. Practically from the outset he immerses us in a complex and riveting tale about deception and betrayal, asking us how far we would go to preserve what we hold dearest.

Essentially it is a novel about good old-fashioned human values. Dybek showcases right and wrong by creating a cast that convinces by dint of their flaws and warped moral choices. Richard is a “bad-tempered brat,” indifferent to the fate of the islanders; Cal’s mother, we learn incrementally, was Gaunt’s lover while her husband was at sea; Cal’s father and the rest of the crew view murder as a necessary evil, an expedient means of achieving the greater good. The novel’s title refers to Treasure Island’s wickedly traitorous pirate, and Dybek takes us back to Cal’s early childhood in which his father would concoct multiple stories of Flint, “Years ago, when Flint was still a good man...” Just as Stevenson’s character was once good, so too was Dybek’s. This mirroring could have been too pat, the sentiment too trite, but neither backfire because Dybek is adept at taking his trick and fashioning it into an inventive, even ingenious, trope. “It’s just stories, Cal,” his father says, downplaying their significance and his creative prowess, and yet in Dybek’s hands Flint’s fabricated back-story becomes as vital as the ‘real’ futures of his own characters.

Literary allusions abound but do not intrude. Stevenson is synonymous with childhood, and Dybek uses him, as Donna Tartt did in The Little Friend, to highlight his protagonist’s youth, before he ages and discovers cigarettes, jazz and Indiana Jones. When Cal overhears his father plotting, he feels like Jim Hawkins eavesdropping on John Silver and the pirates planning mutiny. Later, Cal is older because Stevenson has been ditched for Kafka and Camus. One of the book’s epigraphs comes from Richard II and the various nods to the play are fun: Cal’s father is Henry Bollings; Richard has seized Gaunt’s wealth; and in one inspired scene, a deposed Richard sits incarcerated in a basement wearing a festive paper crown on his head.

Along with bedtime stories and hints of literary tales, Dybek turns Richard into a narrator to recount his life story. Like the fishermen, “He was a storyteller—His stories were dispatches from a kind of life we had never encountered.” Richard comes alive though his yarns; the fishermen, however, don’t, because although we are told of their love of “long talk,” and, tantalizingly, that their “stories were gray, drenched in icy slime,” we never actually hear them.

Fortunately, the core strand is dramatic enough to carry the novel. Dybek is impressive on the transition from childhood to adolescence, with Cal’s slow, sad realization that his parents—one adulterous, the other murderous—are too fallible to be idols; there is a bravura description of a near-drowning in the Bering Sea; and just when we think Dybek has written himself into a corner by bumping Richard off, along comes a neat twist to snare us all over again—to the extent that the novel has more in common with Kidnapped than Treasure Island.

“The incommunicable thrill of things, that is the tuning-fork by which we test the flatness of our art.” So claimed Stevenson in his essay “Fontainebleau.” In this magnificent debut Dybek’s incommunicable thrills shock us and disturb us and make him one to watch.

—Malcolm Forbes

László Krasznahorkai’s novel Satantango is an argument for the vitality of translation. It is bold, dense, difficult, and utterly unforgettable. It is also 27 years old, having first been published in 1985 in Hungary. It was adapted as a stark, masterful seven-and-a-half hour-long film by Bela Tarr years before readers had access to an English-language edition of the novel. In fact it is his work with Tarr which has probably done the most to raise Krasznahorkai’s profile internationally. Besides Satantango, the two collaborated on four other films, including an adaptation of Krasznahorkai‘s novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, a version of Georges Simenon’s novel The Man from London, and The Turin Horse, which is to be Tarr’s final film. Though Krasznahorkai is a significant literary figure in Europe, particularly in Germany, Satantango is only the third of his books to appear in English. Between Krasznahorkai’s talent and legitimately singular vision, and the skill and nuance evident in translator George Szirtes’s rendering of the text, the wait seems justified. It bears mentioning as well that a fourth title, Seiobo, is also forthcoming from New Directions.

The novel is set on a Hungarian collective farm. The residents there seem resigned to a grim, desolate way of life. The locale remains nameless, but the physical details of the estate are highly specific. The buildings—even the ones in use—are in an awful state of disrepair. The owner of a bar laments the spiders which he can’t seem to drive off. One couple’s house has a “dented roof and teetering chimney;” another couple has abandoned a room due to mildew covering the walls, though it also covers their clothes, cupboards, towels and bedding. The rainy season is just arriving to form “stinking yellow mud.” The residents get about mostly on foot and transport things on hand carts or wheelbarrows. The social hierarchy is nebulous at best. Even those with some advantage can hardly be called fortunate, let alone wealthy.

Krasznahorkai largely relegates them to the collective’s grounds, shrinking the stage to fit their personal dramas, the grinding poverty and tediousness of their lives, their pettiness and recriminations. They have no satisfying outlets for their frustrations. Even drinking and sex seem low-level pleasures, taken up indifferently. There is a pervasive sense that they are trapped, that their options are proscribed. Later, when they venture out, rain and fog conspire to limit their view, even in unfamiliar surroundings. Krasznahorkai ‘s control, his authority, is so great that it’s hard not to think of Vladimir Nabokov’s remark that his characters were “galley slaves.”

Lest they should attempt a mutiny, Krasznahorkai traps them amid an absolute torrent of language, description, action, and thought. He is, like Simenon in his romans durs, a great writer of atmospheres, exploiting every bit of the tension embedded in the physical surroundings he chooses. And in Satantango, he saddles them with a tango-derived form which takes them six steps (chapters) forward and six back on their way through the narrative. He offers no paragraph breaks, not even for dialogue. The effect is tense. It leaves the reader no time to pause to draw a breath, let alone reflect. The critic James Wood has written of Krasznahorkai’s “tireless, tiring sentences,” a tendency somewhat less pronounced in Satantango, and compared reading him to “seeing a group of people standing in a circle in a town square, apparently warming their hands at a fire, only to discover, as one gets closer, that there is no fire, and that they are all gathered around nothing.” Striking as it is, perhaps the main thing Wood’s analogy clarifies is how nearly impossible to explain or describe what readers are letting themselves in for when picking up a novel by László Krasznahorkai.

In the case of Satantango, the plot unfolds deliberately. The players gradually assemble on stage, and each successive view joins the others to reveal new facets of the story. One tension is quickly subsumed by another, or so it seems. Later the reader realizes how each concern heightens the others, though Krasznahorkai does not trouble himself with making links immediately explicit or apparent. At one point, before all the particulars are clear, Krasznahorkai observes, perhaps with a nudge and a wink to the reader, that “what precisely happened, that could only be determined by a maximum, joint effort, by hearing ever newer and newer versions of the story, so that there was never anything to do but wait, wait for the truth to assemble itself, as it might at any moment, at which point further details of the event might become clear, though that entailed a superhuman effort of concentration recalling in what order the individual incidents comprising the story actually appeared.”

As more of the picture is revealed, Krasznahorkai’s mastery grows clearer. The sheer intensity of some passages brings to mind advice from the filmmaker Robert Bresson’s book, Notes on Cinematography. “Do not draw back from prodigies,” Bresson writes, “Command the moon, the sun. Let loose the thunder and the lightning.” Krasznahorkai draws back from nothing, not even the destabilizing influence of allowing his fatalistic characters a shred of hope, a touch which elevates the book to still greater heights.

Krasznahorkai is in his late fifties. He is very much a working writer, one young enough that readers can realistically hope for at least a few more books before he lays down the pen. Failing that, English-language readers can wait for the sizable backlog to be translated. His work requires a substantial commitment of both time and attention on the reader’s part, and beyond that, it’s the sort which rewards multiple readings. This first handful of books could easily fill the gap until more appear, even if that takes some time, and Satantango is a fitting place to start.

—John McIntyre