This was supposed to be the year of the economy, an election season marked by differences in creating jobs, reducing the deficit, and deciding the fate of Obamacare.

Yet the first issue of the general campaign that has both major candidates vying for independents is student loans, a markedly more nuanced and lower-stakes debate with no immediate political payoff.

A 2007 federal law cut interest rates on such loans from 6.8 percent to 3.4 percent. If Congress doesn’t move between now and July, the rate will jump back, effectively doubling. The difference would translate into about $1,000 a year in payments for each of 7 million students who would be affected by the new rate.

Most interesting about the issue is the overlap of the parties. For months President Obama has urged Congress to extend the lower interest rates. He devoted his entire weekend address to demanding that lawmakers take up the issue, and made it the centerpiece of a speech at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on Tuesday, urging the crowd to “stand up, be heard, be counted.” Obama also said he and his wife just finished paying off their student loans eight years ago—an implicit contrast with the other Harvard graduate he will face in the fall.

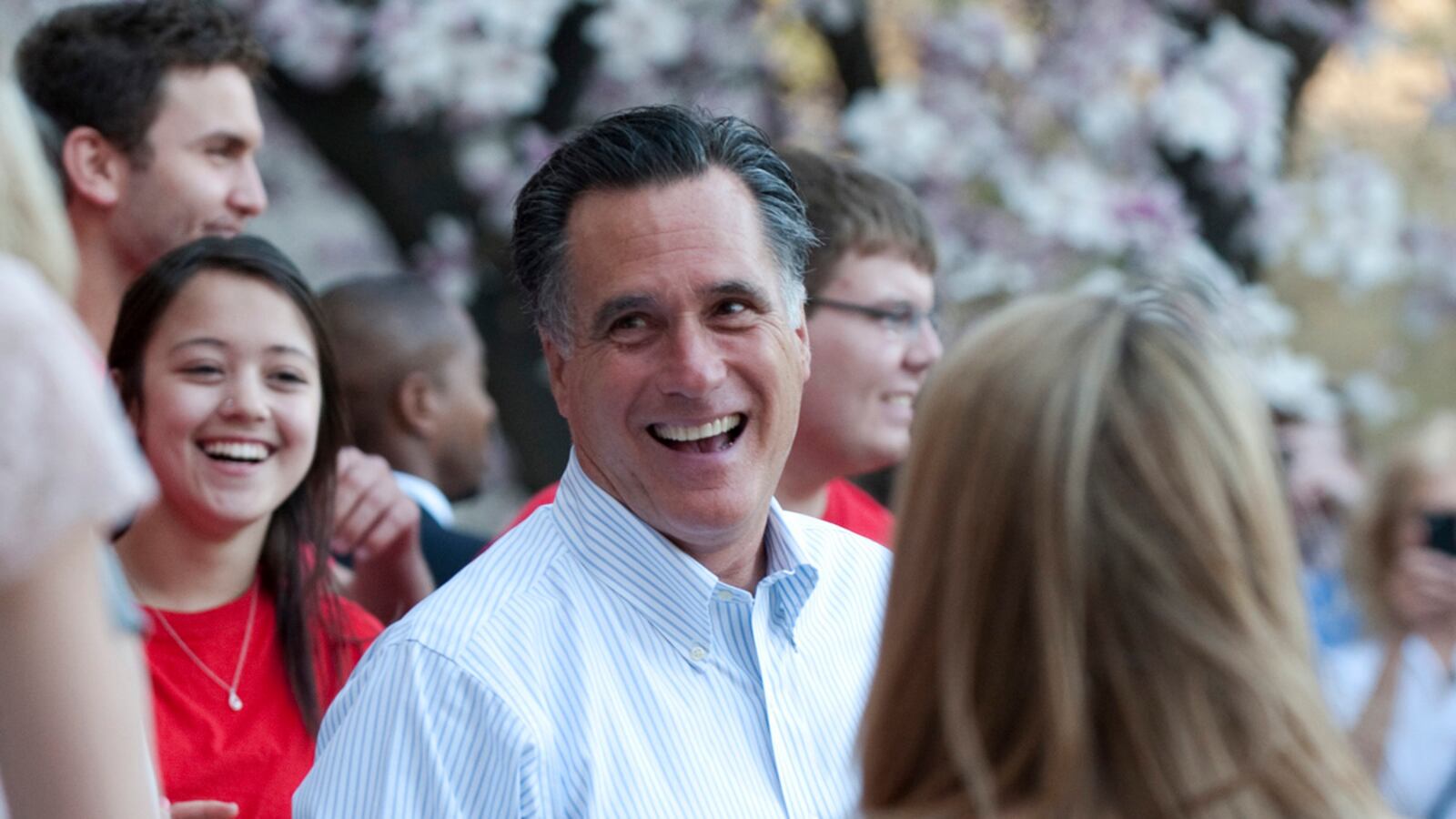

But Romney, interestingly, agreed with the president. "Particularly with the number of college graduates that can't find work or that can only find work well beneath their skill level, I fully support the effort to extend the low interest rate on student loans," Romney told reporters Monday in Florida.

The overlap is the first sign of a larger electoral trend: the play for the middle of the spectrum by appealing to the undecided masses with reasonable proposals. Gone is the rhetoric aimed at Tea Party voters about defunding women’s health care or slashing government programs. Mitt Romney will get their votes. And finished are the impassioned speeches about same-sex marriage and reeling in greedy bankers. Obama will get progressive votes. At stake now are undecided independents.

Student loans may be the perfect issue to test that water. The rate increase would affect about 7 million students, a small fraction of the electorate, which historically isn’t very vocal in elections. In some ways it’s chump change–extending the low rate will cost the government $6 billion–but in a year framed by debates over spending, any money saved or spent is significant.

What’s more, campaigns are inherently about the future, and higher education provides an excellent prism. More people need to go to college, both candidates have said, so the U.S. can compete with the likes of China and other rising economies.

“It’s an important issue, but at the same time it’s small potatoes,” says Sarah Binder, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It’s a pretty sharp discussion for both parties here. It resonates with Romney’s focus for getting jobs for unemployed college students. And with Democrats it’s a perfect issue to champion the middle class.” Binder says it’s hard to imagine many more issues this year on which both candidates will so readily agree.

Despite the political overlaps, both parties and campaigns have been angling for the higher ground. While pointing out that Romney endorsed the House Republican budget that significantly slashed some government programs, the White House has questioned Romney’s sincerity that he now supports programs for the middle class. Romney’s campaign and House Republicans, meanwhile, note that Obama’s budget would return interest rates to 6.8 percent.

There’s still uncertainty over whether Congress will actually do anything. House Republicans have been concerned by the so-called “pay fors,” the series of offsets that would keep the low rates from adding to the deficit. Speaker John Boehner’s office says it will continue working with Democrats to find the $6 billion in the congressional couch cushions. But there’s reason to believe it will get done by July 1. On such a populist issue, neither side is interested in a cycle of negative headlines accusing them of obstruction.