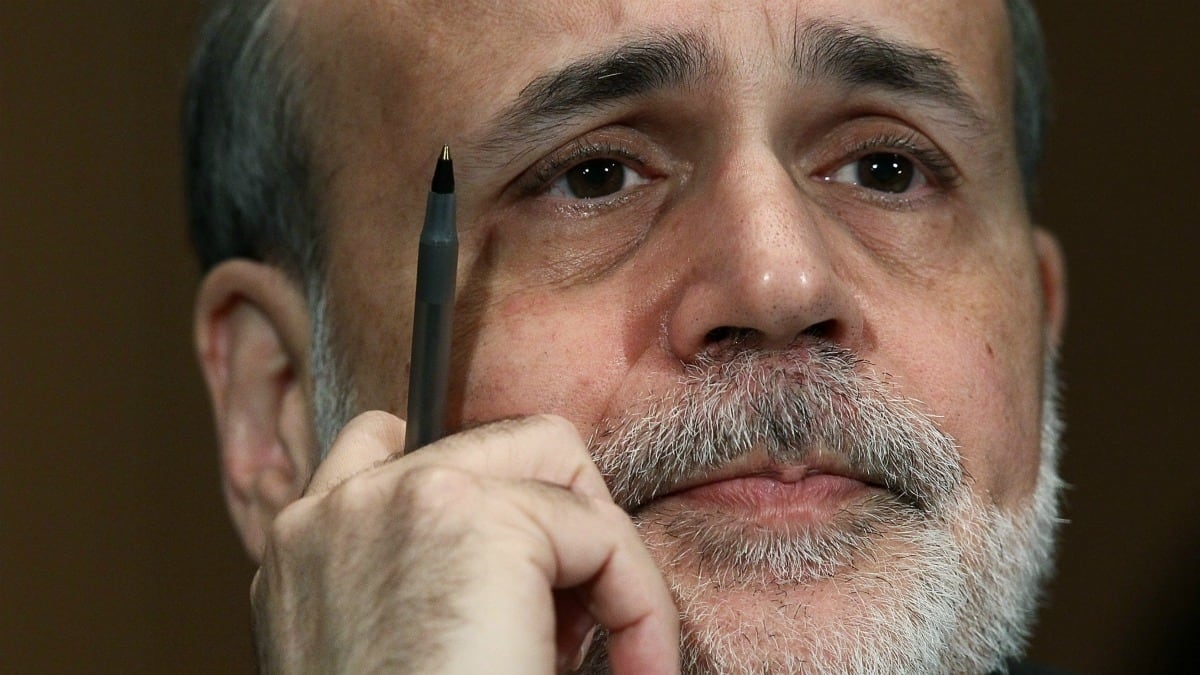

One of the biggest questions in the economics blogosphere has been: "Why is the Federal Reserve repeating the same mistakes that Japan did even though its Chairman has blasted Japan for its own inaction in response to its economic crisis?"

Paul Krugman takes a stab at an answer in the New York Times Magazine. It contains a lot of analysis that will be familiar to those who have been following these debates since the Fed's second round of quantitative easing, but I want to focus on the part of the piece which really highlights how doomed we all were.

I had long assumed that the main problem facing the Federal Reserve and Ben Bernanke was the political pressures being arrayed against him: a Conservative movement and Congress that was prematurely calling for tighter money and a President who showed no interest in fighting aggressively for FOMC board members.

Yet Krugman cites a new study which suggests that Bernanke had moderated his stance long before the crisis even began:

Recently Laurence Ball of Johns Hopkins University made waves among monetary economists by looking through Fed minutes to determine how and when Ben Bernanke’s views changed. According to Ball, Bernanke’s big retreat from F.D.R.-like resolve happened way back in 2003, less than a year after he arrived at the Fed. That month, a Fed staff report rejected many of the ideas Bernanke previously supported — and ever since, Bernanke has spoken only of limited responses to the problem of the zero lower bound. What’s puzzling about this apparent conversion is the fact that while Bernanke may have been a newbie at the Fed, he was a towering figure in his field. Why should he have taken his cues from a staff report?

Ball emphasizes both the pressures of groupthink and Bernanke’s shy personality. Without necessarily disagreeing, I’d point to a crucial difference between the policies Bernanke advocated in his pre-Fed days and the ones he has supported since 2003. His Fed-era policies aren’t simply less ambitious than those of his academic era; just as important, Chairman Bernanke’s policy menu, unlike Professor Bernanke’s proposals, has been set up so that the Fed can’t be blamed for failure.

Suppose, for example, that the Fed announces a higher inflation target. It might not work: markets might not consider the Fed’s proclamations credible and believe instead that no matter what the Fed says now, it will return to its traditional focus on price stability. So an attempt to raise expected inflation could lead to an embarrassing failure. When buying government bonds, on the other hand, the Fed can always claim that the policy worked, even if the economy does poorly, because it can insist that things would have been even worse without its actions. So by retreating to a narrow definition of the Fed’s role, Bernanke has also adopted a position that is much more comfortable for the Fed as an institution.

Back in 2000, Professor Bernanke warned against exactly this kind of retreat, harshly criticizing the Bank of Japan’s unwillingness to “try anything that isn’t absolutely guaranteed to work.” But within a year of his arrival at the Fed, he seemed to have been assimilated by the Fed Borg, like Capt. Jean-Luc Picard in a famous “Star Trek” episode, converted into a half-robot servant of a hive-mind.

I had thought that the obstacles to effective Fed policy began with the "Open Letter to Ben Bernanke" issued in November of 2010. It turns out that Bernanke was already moving towards a more limited role of what the Fed could do even earlier.

This is pretty remarkable stuff and raises a frightening question: if this is what happens to someone who used to espouse aggressive monetary policy, what will happen to someone more timid? It is highly unlike that a President Romney will reappoint Bernanke and its not clear Obama would either. How likely is it that the next Fed Chairman will be more likely to prematurely raise interest rates, no matter who controls the White House?