April 29, 1992, was one of the saddest days of my life. I was an assistant to Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley at the time, working on issues of homelessness and economic development—things that were directly related to South Los Angeles. The evening after the verdict of the Rodney King trial was announced, we in the mayor’s office had planned to meet at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church with religious leaders, elected officials, and members of the community to discuss—regardless of the verdict—what we can do better in Los Angeles. How we can have a police department that respects the community, and how we can insure that incidents like King’s beating don’t happen again.

I was on my way to the First AME Church with one of my friends from City Hall. I had the radio on in the car, and we were listening to the verdict and we heard the pleas of the people on the radio saying, “Do not get out of your car.” I had just pulled off the freeway at Western, and was close to Western and Adams when we heard the people on the radio talking about everyone leaving the First AME Church. My friend and I decided it would probably be best to turn around and go back to City Hall. So that’s what we did, and that began a long night and a long several days of responding to the civil disturbance.

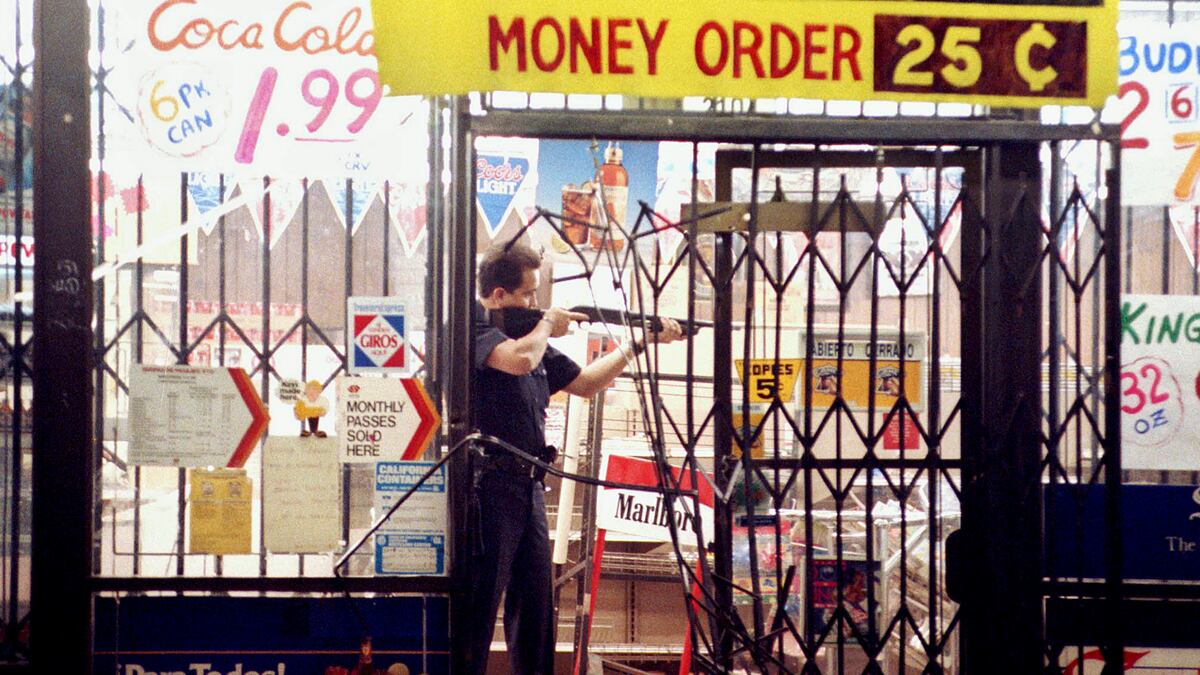

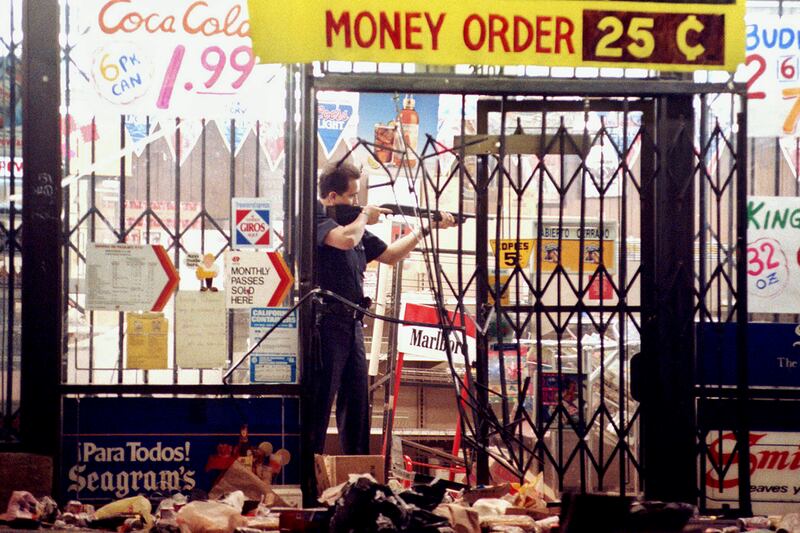

Back at City Hall, all hands were on deck. As we were responding to press calls and trying to get the message out to stop the violence, we could see smoke coming up from bombs that had been thrown at the floor of our building. We could see palm trees on fire outside our office, and just blocks away protesters were outside the police department.

I’ll never forget my drive home that night. We were all escorted to the freeway, and there was absolutely no one on the freeway. In Los Angeles, having no one on the 101 Freeway is a big difference from a normal evening. I saw National Guards in the San Fernando Valley, where I lived, literally sleeping on the sidewalks on Sherman Way. It was something I hope never to see again. I remember thinking, “This is not the Los Angeles I grew up in.” It was a feeling of sadness, one of, I guess, a resolution to do anything I could to ensure that, particularly in South Los Angeles and in Koreatown, we rebuild.

That Saturday following the riots, I drove around with one of my co-workers to some of the areas that had been devastated—areas where we had both worked for years to create economic development—and literally both of us had tears running down our faces. We saw buildings that we had worked on burned to the grown.

I worked with Mayor Bradley until he left office in 1993, and during that time we were just focused on rebuilding. We also were determined to convey to the rest of the country that Los Angeles was not unique in the kinds of frustrations that led to the riots.

I particularly believed that from the ashes of the unrest we could work to sprout new hope for our community. That was a dark day for us but one we could learn from and work to make sure never happened again. There’s always been a lack of educational and economic opportunities for children growing up in South Los Angeles. There have always been inequities. But when the city erupted, it was a stark reality check.

Some of the major questions at the time were: Were the police prepared? Was there enough communication between the police department in the different areas? After that we made sure that the many recommendations for improving the LAPD were actually implemented, that the chief had a term with limits, and that the LAPD leadership and the mayor and city council all had a working relationship. And things have actually improved. Clearly, there have been some blemishes on the police department since ’92, which have also been catalysts for change, but I believe we have turned a corner. There is a big difference between 1992 and 2012; the LAPD has done a good job trying to reach out to those neighborhoods and respond to them, and they continue to evolve and learn from those mistakes.

I don’t think anyone ever anticipated the violence that would occur following the acquittal of the police who beat King, but I think to understand what happened you have to look at the root cause of why people were frustrated. Many of the areas where the riots took place were food deserts, devoid also of sufficient economic, educational, and housing opportunities. In the aftermath, though, we saw the creation of a lot of national legislation focused on empowerment and enterprise zones across the country that look at how we can ensure that some dollars get to low-income areas.

In the days following the civil disturbance we had a lot of dialogue, a lot of sitting in rooms and debating the cause of racial tension and how to understand where people were coming from. There’s nothing like sitting in a room and baring all with the ultimate goal of saying, “We want Los Angeles to be the best Los Angeles possible.” There have also been a lot of efforts to cultivate a better relationship between the African-American community and the Korean Community. Tensions still exist between these two groups, but the area is not as polarized as it once was. A strong influx in Latino residents has contributed to the representation of various ethnic groups in the community.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles, as was my father. This was a city that we all felt like we were a part of, so to see that racial strife was devastating. But, on the flip side, it made me want to commit myself to rebuilding Los Angeles. I am running for mayor now because I feel that we have an opportunity to address these inequities. We have an opportunity to say to the rest of the country: in many cities, there are big parts of your communities that also feel these economic injustices and you can’t ignore it.

If there was one message I took from this experience, it’s that we are one city. Yes, we are composed of small communities in different places, but ultimately we are one city. And you should care about your fellow man or woman in other parts of the city and should want to insure that they have economic and educational opportunities.

Our work is not done. I’ve been watching a lot about race in America on the news lately, and it shows me that we still have a long way to go for people to accept one another. There are a lot of similarities between the current Trayvon Martin case and Rodney King. But I hope that what happened following the verdict of the King case doesn’t happen again. I think that people understand now that that kind of violence is not acceptable. I hope people have realized that they can use their voices to protest and advocate and ensure that justice is carried out. There are avenues through which people can make their voices heard without creating a repeat of what occurred in 1992.

But I’m an eternal optimist.

As told to Caitlin Dickson.