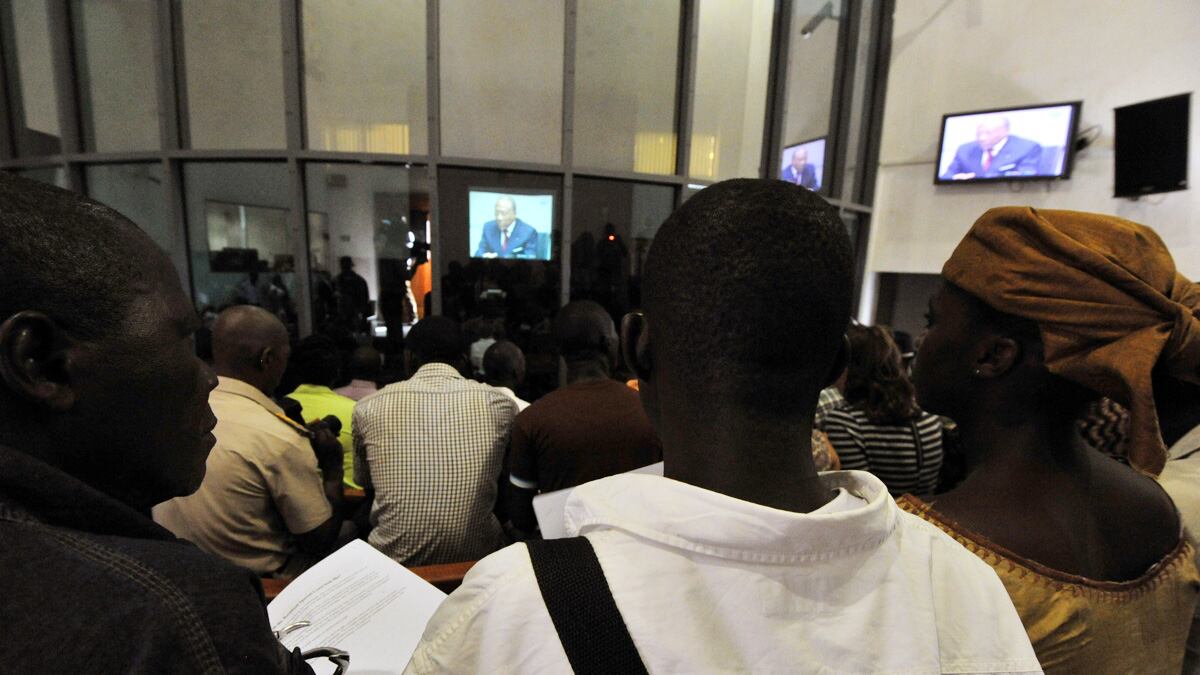

They sat stock-still on the hardwood benches of the dank, makeshift cinema in Monrovia. All eyes were fixed on their former president Charles Taylor, broadcast from the dock at The Hague courtroom of the Special Court for Sierra Leone. For almost three hours, Presiding Judge Richard Lussick rendered in sober monotone the court’s judgment on Taylor’s involvement in Sierra Leone’s brutal late-1990s war. One of Africa’s most infamous warlords and the man who oversaw Liberia’s descent to dystopia was, at last, found guilty.

It took more than five years and 50,000 pages of convoluted testimony for the U.N.-backed court to reach its conclusion. Fragmented conflicts involving loosely affiliated militia-gangs operating across porous national borders do not distill neatly into watertight international prosecutions. The court, while unconvinced of prosecution claims that Taylor was the mastermind of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), found him guilty of aiding and abetting their atrocities with financial, military, and logistical support.

On hearing the news, the watchers sat quietly for a few moments before filing out into the late morning sun. No celebration, just contemplation. Taylor’s pariah status abroad was never reflected at home, where he occupies a curious place in the national psyche. All in Liberia are painfully aware of the suffering Taylor caused. Still, there remains to varying degrees a lingering sense of dissatisfaction about his fate.

Liberia was a novel idea conceived in the United States in the early 1800s, an experiment in sending freed slaves “back” to Africa. In thrall to the U.S. culturally, perennially reliant on its aid and investment, “America’s stepchild” has never really controlled its own destiny. Consequently, there exists among many a prevalent belief in an amorphous, omniscient “international community,” spearheaded by the U.S., holding the puppet strings. Taylor’s downfall, they believe, is what happens when an impudent Liberian leader starts to lead his own dance.

“We feel there are heavy, heavy hands behind this,” says Robert Lupu, 30, one of those who spy a conspiracy. “It was always to happen to Taylor.”

Taylor’s ascent began in 1984 when he mysteriously walked out of a high-security Massachusetts prison. His escape is widely believed to have been facilitated by the U.S. government. (Earlier this year long-suspected links between the U.S. intelligence services and Taylor were finally confirmed). After undergoing guerrilla training in Gaddafi’s Libya with a collection of other aspiring African dissidents, Christmas Eve 1989 saw Taylor reenter his home country from the north with around 100 revolutionaries.

The Liberia he entered was already well on its way to ruin, seething with ethnic strife thanks to the increasingly brutal policies of President Samuel Doe. This former army-sergeant had been plied with U.S. aid while a valuable pawn in Ronald Reagan’s African Cold War game. But by the end of the 1980s, he had outlived his usefulness. Taylor, an ever-ebullient presence, was viewed as a liberator by suffering Liberians, and had strong support from those exiled in the diaspora.

This dissipated as the anticipated quick revolt turned into an astonishingly brutal and prolonged war. Other warring factions formed, seeking a slice of the pie. And President Clinton’s administration, chastened by recent events in Somalia, did not intervene. It was not until a 1997 election, with 10 peace agreements having come and gone, that Taylor would finally take power. A country tired of war voted overwhelmingly to give him what he wanted. The warlord had become a democratically elected president.

Taylor the president filled his pockets with Sierra Leonean “blood diamonds,” stymied freedom of speech, and reportedly shielded Al Qaeda operatives. The U.S. lost patience, finally deciding to “twist” the errant Liberian leader from its ever-shifting card hand of favored autocrats. Embassy cables confirm that in 2001 the U.S. began a concerted campaign to oust Taylor. By 2003, two former Pentagon officials had unsealed an indictment against Taylor. Congress would pass a bill offering $2 million for his arrest. Amid vicious fighting with rebels who had reached the capital, Taylor was on his way. Standing up from a gold-painted throne to say farewell before going into exile, he told the nation he had “accepted this role as the sacrificial lamb ... I am the whipping boy.” But for Taylor there would be no cozy end in exile as Idi Amin had. In 2006, ahead of a planned meeting, pressure from George W. Bush on Nigerian President Olusegun Obsanjo saw him extradited to stand trial.

While only 20 years old, Prince Valentine laments the selectivity inherent in international justice. “Lots of leaders do the wrong thing, especially in Africa. But not all go to the court.” And glancing across the continent, many of Taylor’s contemporaries have fared rather better. Former rebel Yoweri Museveni was declared one of a new type of African leader, before he started to look like rather an old type of African leader. His friend to the north, Paul Kagame, is another authoritarian with grubby hands, feted nonetheless.

“I feel sad he be going to jail, even though he committed atrocities,” says Paye Sendolo, 42, from Monrovia. “Why does Liberia never get to have ex-president? They are all killed and now he’s in prison, taken from us too.” In Liberia, sadly, patriotic shame about the country’s bloody past only seems to afflict those who had no control over it. What most Liberians yearn for is a normal past, present, and future. Normal countries have former presidents as statesmen. “Great men like Bush and Blair,” Sendolo adds, sadly, perhaps not aware of the calls from some quarters for the Western leaders of the Iraq war to be prosecuted.

Alice Yekeh, 45, originally of Lofa County, while seemingly content with the verdict, is more concerned with realities closer to home. “I don’t think he meant it to be this way, but Taylor brought the war here”. She is angry that Liberia’s other warlords are, as she puts it, “still eating.”

The Liberian civil conflict was a bewildering alphabet soup of acronyms, each a rebel group led by a warlord. All are acknowledged to have committed similar atrocities. Yet as Taylor heads for prison, the other rebel leaders thrive. Most notably, Prince Yormie Johnson, who split from Taylor and formed his own rebel group early in the war, is a senator who came third in the country’s recent presidential election. Alhaji Kromah, founder of the ULIMO-K group, is a university professor who President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf recently appointed ambassador-at-large. Dr. George Boley, formerly head of the Liberia Peace Council, returned to Liberia from the U.S. last month under a removal order made by a U.S. judge using the 2008 Child Soldiers Accountability Act.

All were recommended for prosecution by the country’s postwar Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But they have little to fear in Liberia, where Nobel Prize winner Sirleaf has swept the report under the carpet.

This is probably because she’s mentioned in it too, recommended to be barred from office for 30 years due to her early support and financing of Taylor. The internationally popular president, understandably, avoids the topic. When traveling across Liberia reporting on her reelection bid last year, I was struck by how frequently I was told that life was “better in Taylor-time.” Liberia’s poor majority have, in recent years, been badly hit by spiraling global food costs. Taylor, while accruing millions of dollars for himself through high-level racketeering, was keenly aware of the significance of affordable foodstuffs in maintaining order, and subsidized them accordingly.

However, financial realities are only one aspect of a sort of “Dictatorship Nostalgia” that one often hears expressed in Liberia. By all accounts, there is just something about Charles Taylor.

“The old ladies would crawl to the road, just to put eyes on Taylor. Can you imagine?” Alfred Sargbah, a longtime devotee of Taylor, tells me. “Now, president car goes past, nobody care. Is that right?”

Paul, 31, was close enough to Taylor that he must speak in anonymity. He joined Taylor’s fledgling rebel movement as an 11-year-old, and quickly became a favored bodyguard to the man himself. As a fly on the wall throughout Taylor’s rise, he is able to provide an intimate portrait of the warlord he still calls “the Chief.”

“It was all about his personality. Taylor was the man who could meet you once, then see you in a line of 1,000 and call your name out. He always had time for anyone, he was never unfriendly.” Paul smiles at the memory. “He always had something for everyone that came to him. Everyone from the outside got something. He was kind, he was so kind. You know, Taylor paid all of the other rebel leaders’ hotel bills at the peace talks.”

This “kindness” was actually an intrinsic part of Taylor’s strategy, a counterpart to his ruthlessness. Patronage is a deeply embedded social norm in Liberia, a potent strategy in a place where so many have so little. I look after you, so you belong to me. Academic William Reno, in his 1999 book Warlord Politics and African States, describes how Taylor ran a “shadow state” based on personal links. Formal administrative institutions were largely impotent. Taylor was perfectly formed for the intuitive, opportunistic life of a rebel, but not for the stolid bureaucracy of government. Paul remembers how “everything collapsed as soon as he left (for exile in 2003). Because everything was built on him.”

Even amid the pressure of maintaining such an unstable power base, Paul recalls an unflappable leader. “He was never afraid, always normal, playing tennis at his house. When you see your leader like that, you follow, you believe. He was incredible.”

It was not only young lieutenants like Paul that were enchanted by Taylor. For a period, the BBC became his loudspeaker to the world, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Clinton’s special envoy to Africa, his cheerleader. Far from a crude warlord, he was a chameleon, equally comfortable as a preacher or a warrior. His light skin and East Coast U.S. inflection allowed him to project the superior suaveness of Liberia’s Americo-Liberian elite, while simultaneously taking on the Gola middle name “Ghankay” to inflate his grassroots appeal.

For those who campaigned against this formidable opponent, his downfall is sweet. Tiawan Gongloe, one of Liberia’s foremost human-rights activists and lawyers, is cracking open a bottle of champagne. He was tortured for his outspoken criticism of Taylor’s regime. “This is an absolute landmark decision. People thought he was invincible, that no one could deter him. He thought that. This is a decision that can change the mindset of our people.” For Gongloe, the dividends of the verdict dwarf the $250 million cost of the trial. “I don’t believe there is any monetary value can be put to anything that brings about sustainable peace for us.”

Any conversation on future peace in Liberia inevitably turns to the country’s thousands of ex-combatants, many of them Taylor’s child soldiers now grown. They are his most poignant, potent legacy.

When researching a recent article on the postwar experience of some of these young men, I was struck by the fact that the only person who escapes blame for their present predicament is the man who bears greatest responsibility: Taylor. For many, the coming of peace signaled the permanent loss of respect. In Monrovia, they squat in the crowded spaces between lavish compounds, the towering walls of which are a reflection of the mistrust that corrodes post-conflict reconciliation in Liberia.

When I was last here, in the old GSA slum on Monrovia’s 25th Street, I brought up the impending trial verdict. One by one, they made me write down their names in my notebook, insisting I “tell the whole world and Barack Obama that Charles Taylor should be free.” These young men continuously mythologize Taylor. They tell fables of his bravery, of his sexual exploits, of a blue diamond he had that was “almost the size of your head, I swear!” For them, most from poor country families, the lavish Taylor with his absolute power was no ordinary man.

On the afternoon following the verdict, amid their melancholy, they are taken by a strange phenomenon that appeared in the Monrovia sky around midday. Around the sun, a perfect circular halo has formed. “It’s from him!” says Sam Hassan, 31. “He is telling us all will be fine.”