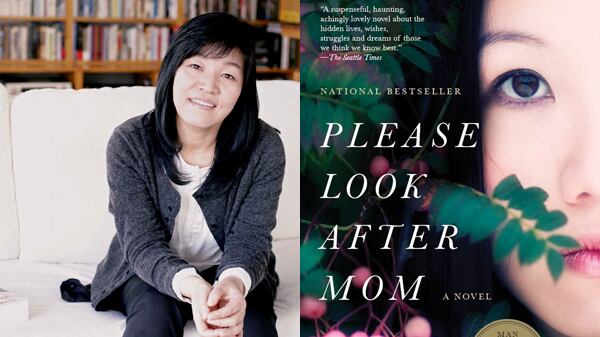

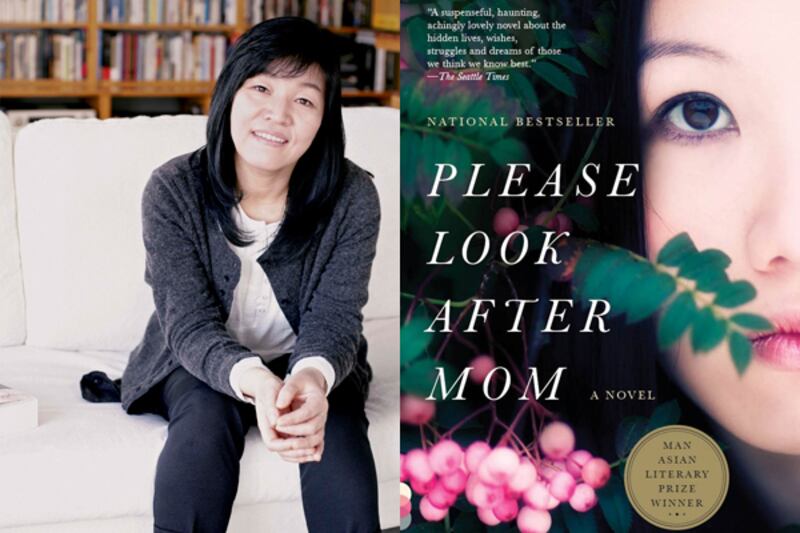

Kyung-sook Shin would like everybody to know that she knows exactly where her mother is. In March, Ms. Shin became the first Korean and the first woman to win the Man Asian Literary Prize—beating out Haruki Murakami, Amitav Ghosh, Rahul Bhattacharya, Banana Yoshimoto, and other worthy rivals —for her novel Please Look After Mom. Published in English in 2011, and translated into 32 languages, the book tells the quietly devastating story of a hard-working, illiterate rural mom who goes missing (for good, it would seem) in a bustling Seoul train station, during a trip to the big city to visit her neglectful grown children—her businessman son, and her writer daughter.

At a café in New York, where she traveled last month for a whirlwind tour accompanying the paperback release of her novel, Ms. Shin recalled through an interpreter, “After my book came out, a Korean woman writer called me and asked, ‘Did you find your mother?’ She thought the story was completely real.” Modest but confident, with long, smooth hair and a gentle demeanor, Ms. Shin conceded that, “The mother in this novel is maybe a little bit like my mother,” but emphasized: “She is different, a fictional creation.” For instance, while her own mother does in fact prepare the homemade foods that appear in the novel, like sesame-leaf kim chi, stewed beef, and fermented bean paste soup, she is not illiterate. “She reads the Bible all the time,” her daughter said. Still, she does not know for sure if her mother has read the novel: “I was too shy to ask her if she liked it.”

It would be easy to take the story of Please Look After Mom at face value, but Ms. Shin warns against over-literal interpretation. “It’s the mother who goes missing, but that’s a metaphor,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be the mom who disappears; it could be anything precious to us that has been lost, as we’ve moved from a traditional society to a modern society.” In the West, that shift took place more than half a century ago; but the transformations that Ms. Shin’s novel charts are of more recent vintage, and occurred in the author’s lifetime, as democracy and prosperity in South Korea flourished. But she believes that enough overlap exists between Eastern and Western cultures to give her themes global resonance. “Kids nowadays are definitely different from the traditional generation that came before us. And I don’t think that’s restricted to Korean society.”

Like the daughter in the novel, Ms. Shin, 49, left behind her farming family in Jeolla Province when she was a teenager, to live in South Korea’s capital and earn money for her education. “I was sixteen when I left the countryside and moved to Seoul,” she remembered. “On the night I left home, my mother traveled with me. I thought to myself then that, one day, when I became a writer, I would write something to remember my mother by,” she said. “But this book was a long time coming.”

Ms. Shin is well-known in South Korea as a prolific author of short stories, essays, novels, and novellas, and as a writer of conscience who uses the written word to “give a voice to women and children and other people who are marginalized,” as she puts it. She insists that she seeks no public role; but in her acceptance speech at the Man Asian awards ceremony in Hong Kong last March, she called attention to the plight of North Koreans who flee to China, only to be sent back home, where they are executed. “Korea is the only divided country in the world, and it’s been more than a century since the country has been divided into two,” she said. “But now, people who have fled the North and arrived in China are being sent to back to the North. People who left the country in order to gain a life are being sent back to their deaths. I want the world to know this story.”

In that speech, Shin also explained that it was literature that got her “through hard times and sad times,” as she grew up. Until now, the best known Korean-born contemporary writer has been Chang-rae Lee, who moved from Seoul to the United States at the age of 3, but Ms. Shin is planting laurels in their native land, and tongue, though her inspiration is global. “I love Chang-rae Lee’s book Native Speaker,” she said. But the novel she rereads every year is Camus’s L’Étranger. “Each time I read it, I get something new,” she explained. In 1985, she published the novella “Winter’s Fable,” which won her South Korea’s Munye Joongang New Author Prize; but Ms. Shin continued working as a journalist and editor until 1993, when the success of her story collection “Where the Harmonium Once Stood” established her as a literary groundbreaker, and let her quit her day job.

“In the United States, because it’s the first book of mine they’ve seen in English, some people think I’m a first-time writer, but I’m not,” Ms. Shin said. “I’ve been published for more than 30 years in Korea. It’s not something that’s happened overnight, like “A Star Is Born.” Please Look After Mom is her sixth novel (her seventh, which has the working title “I’ll Be Right There,” is being translated into English, for Knopf). “I was blocked for the longest time on this book,” she said. “But one night in 2007, a sentence just came to me whole: “It’s been one week since Mom went missing.” That sentence became the first sentence of the novel. “The book I ended up writing turned out to be totally differently than I’d initially envisioned it,” Ms. Shin said. “In early versions I made the mother a heroic figure. But along the way, I realized I needed to make her into a real human being, a person with flaws; not a hero mother, but a human mom.”

Anyone who reads Please Look After Mom may conclude that there is not necessarily much of a difference between the two. Near the end of the book, the writer daughter character recalls a dream in which her missing mom meets her own mother (the protagonist’s grandmother) in the afterlife. She thinks to herself, “Did Mom know? That I, too, needed her my entire life?”

“When I wrote that line, “ Ms. Shin said, “I felt I had done it; that I’d said what I needed to say. I wanted moms to know that they are needed, that they are essential. And not only that: I wanted to show that even moms need moms.”