It seemed like a smart idea at the time: take the British artist Tacita Dean to lunch at a classic American diner. After all, next door at the New Museum, she had just put the finishing touches on a show called “Five Americans,” the latest presentation of her famous cinematic portraits, which opened this past weekend. But instead of ordering a Yankee burger or Southern biscuit, Dean had to go asking for a Greek salad and Canadian bacon, washed down with several cups of English breakfast tea. And saying things like, “I don’t see how anyone could find any national identity in these works. It’s more European.”

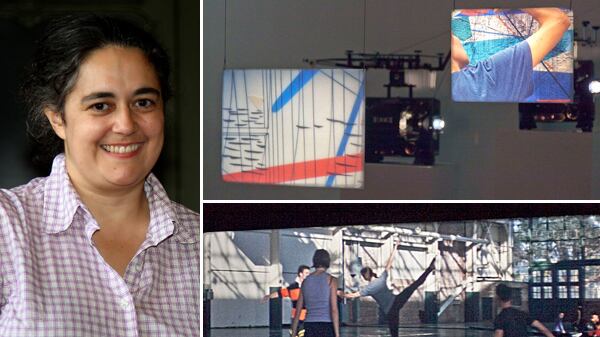

Dean’s New Museum portraits, projected from old-fashioned film, give us lingering views of the iconic American creators Claes Olbenburg, Cy Twombly and Merce Cunningham (those last two have died since Dean filmed them), and of their much younger colleague Julie Mehretu, a well-regarded painter from New York (but who was filmed during a stint in Berlin, where Dean has lived for a decade). There’s also a five-photo portrait of the art historian Leo Steinberg, yet another subject who passed away after his session with Dean. “I have a bit of a reputation as a grim reaper,” she says, with her typically diffident smile.

Dean explains that not one of these sitters was chosen “because of their American-ness.” The title came about pretty much by accident: “It was going to be ‘Four Artists’—but then there was Leo,” she explains. Including the non-artist professor forced the final title.

Yet the original conceit would have captured what’s key in these works. Imagine if Vermeer had painted portraits of Rubens, Bernini, Rembrandt, and van Dyke. That’s about what we have here: One artist known for an endless observational patience, depicting four others whose art is high-impact and lively.

A year ago, I named Dean one of the 10 most important artists of our era. Others share my opinion: this spring, she had the honor of filling the cavernous Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London with a complex projection she’d created just for the space. (“Everyone said it was simply impossible. And they were right.”) At 46, she has achieved about as much as any artist could hope for: She’s received the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss prize, with a purse of $50,000, along with invitations to two Venice Biennales and the upcoming Documenta art festival, a solo show at Tate Britain, and another, in planning, at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum.

Dean’s work has a depth and complexity that we normally prize in the art of past ages. It doesn’t make an argument or send a message. It just is, but in a way nothing else has quite managed to be.

In her New Museum portrait of Cunningham, Dean spends 108 minutes showing us the wheelchair-bound choreographer as he rehearses one of his last projects, a dance called “The Craneway Event” that he staged in a vacant factory overlooking San Francisco Bay. In a series of long, poised takes, Dean records the dancers responding to Cunningham’s promptings, and working to capture his vision. A lot of the action is filmed in silhouette against the gorgeous view beyond. The sense of peace and order, shot through with glancing light, is fully Vermeerian.

Dean’s portrait of Twombly is even more mellow. We watch the artist contemplating sculptures in his studio, and eating a quiet lunch with some friends. The simple, still presence of this person, approaching the end of his days, is an antidote to the noxious ogling a camera might normally give to a superstar painter. It speaks to how much of even the most famous artist’s life is filled with stillness, rather than action. Dean’s counterintuitive goal, she explains, was “to make a film about an artist— and he just sits there.”

Oldenburg is equally still in his portrait, titled “Manhattan Mouse Museum.” That’s the name the artist has given to his 50-year collection of odds and ends pulled from the street—toy ray guns and plastic Mickey Mouses and suggestive morsels of trash. Under the ever-watchful eye of Dean’s camera, Oldenburg sorts and re-sorts his finds, dusting them off and checking them out, as we simply watch him being him.

Even when Dean films the much younger Mehretu, working with assistants on a vast, busy mural, the footage seems to capture all the moments where the artist is thinking, or quietly making meticulous marks. However noisy art can seem when it’s finished, Dean depicts it being born out of stasis and thought.

And as the artist is quick to point out, her film’s quietude is hard-won, achieved with as much labor as any oil by Vermeer. “It’s all in the editing,” she says. “It’s my artifice.”

She cuts out every moment where her subject seems at all aware of her buzzing camera and crew, until all that’s left is a removed, God’s-eye view of an artist at rest. Oldenburg, for example, started out much too alive to her presence as she filmed. “I was starting to panic by the afternoon – there was almost nothing I could use.” And then she came up with the idea of asking him to fiddle with his collection of detritus. “All those objects—it’s like his whole career is there ... It was all about me trying to coach him out of his awareness of the camera.” Oldenburg just “being himself” is, in fact, Oldenburg as cast for a Tacita Dean production.

Regardless of the subjects that Dean treats (she’s also shot pears in bottles and Budapest’s steam baths), her films provide relief to anyone caught up in the chaos of our age. In her hands, celluloid comes off as a medium that allows for old-fashioned rumination, with some of the slowness of oil paint. The whirr of the projector, the flicker of Dean’s grain have a wonderful lulling effect, helping life on screen unroll at a pace that’s been lost in the world outside.

As a famous artist in constant demand, Dean understands this contrast as well as anyone.

During her 17 days in the United States, she’s installing and opening her New York show, dropping by another in Chicago, heading to the Getty Center in Los Angeles to talk about the coming extinction of film (she’s a crusader for its survival), then dragging a crew through the desert in Utah to shoot her latest film. Before leaving Germany, she’d been so frantically at work on a series of drawings that, in rubbing at their surfaces, she’d also half rubbed off her own fingerprints. (U.S. immigration was not amused, she said, and they pulled her aside for extra screening.)

And this running around, which we all suffer from, is twice the torment for Dean. She has crippling arthritis that leaves her with a vicious limp, and with hands too tortured to hold a cane. It’s no wonder she cherishes that vital moment in her process when she gets to sit alone in her editing room, cutting an artwork from her endless spools of film. “This is really important about me,” she once insisted when we spoke. “I don’t have any conscious path at all. I don’t want to know where I’m going.”