FEAR AND LOATHING IN PRAGUE

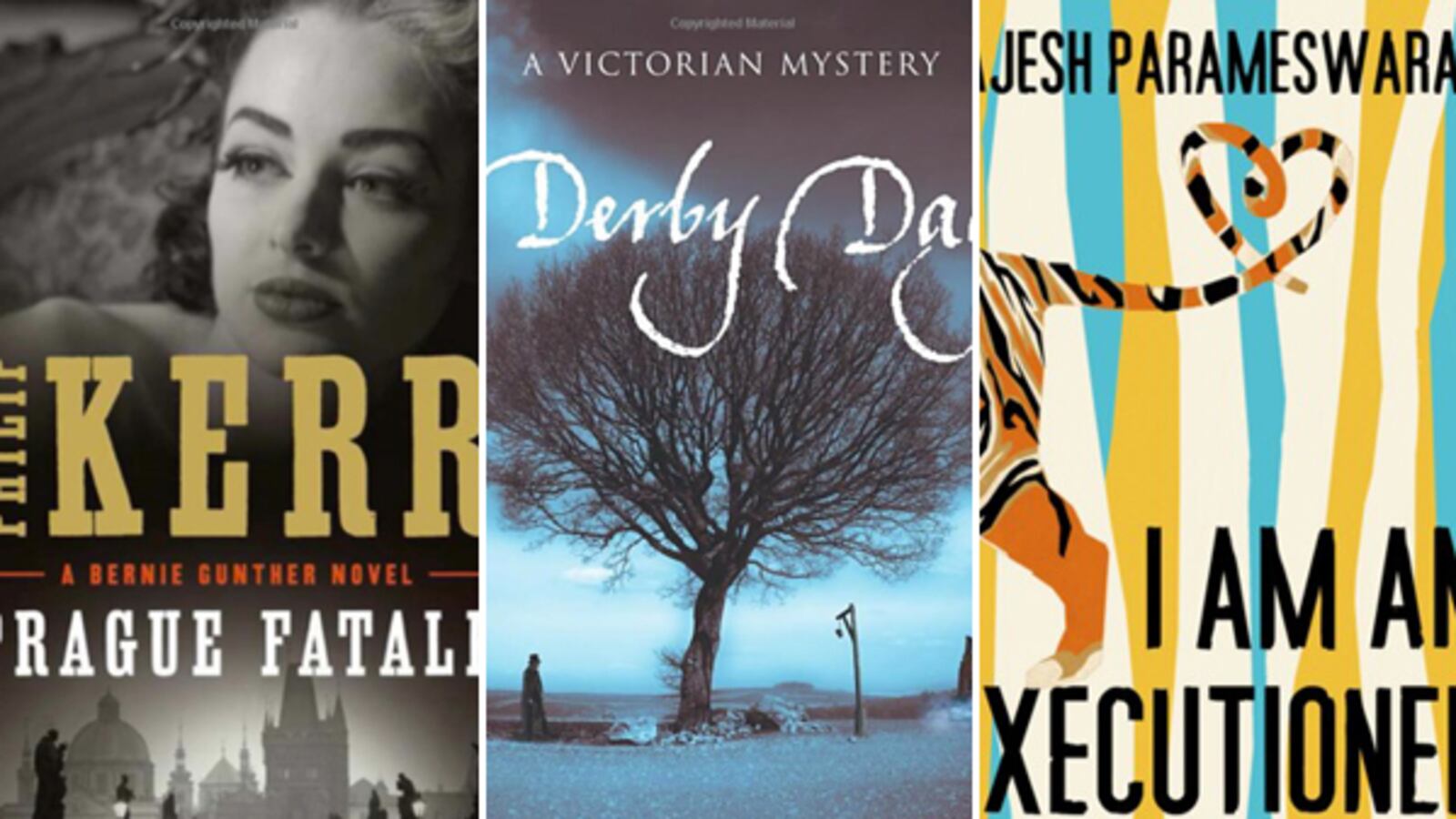

Prague FataleBy Philip Kerr 416 pages. Putnam. $26.95.

Bernie Gunther, Philip Kerr’s hard-boiled Kriminal Commissar, is back. As with the other books in Kerr’s consistently superlative series, Bernie finds himself caught up in history and struggling to maintain his sanity and conscience among “Hitler’s myrmidions.” Kerr has let his grizzled gumshoe yo-yo through the dark years of the Third Reich and beyond: March Violets (1989) saw Bernie tracking a killer against the backdrop of the 1936 Berlin Olympics; A German Requiem (1991) placed him in postwar Vienna; A Quiet Flame (2010) took him to 1950’s Argentina with Eichmann and Mengele. This time we are back in 1941 and flit from Berlin (“the capital of a banana republic that had run out of bananas”) to Prague.

Reinhard Heydrich, Reichsprotector of Czechoslovakia, fears he is the target of an assassination plot and summons Bernie to his castle outside the capital to keep an eye out for trouble. During a weekend gathering comprising Nazi Party grandees, one of Heydrich’s adjutants is murdered. Kerr unleashes a tale that skillfully blends police detection with political intrigue, peopling it with fully fleshed characters that are both his own creations and real-life incarnations. The rules are changed and the stakes heightened when Bernie learns he is hunting not only a murderer but also a traitor among the ranks who is spying for the Czechs.

With this shift, Kerr elevates Prague Fatale from a standard police procedural (albeit one with a unique historical setting) to a thriller with greater scope and more complex ramifications. The whodunit is fun—a baffling Agatha Christie-esque locked-room mystery—and a novel departure from Bernie’s usual noirish metropolitan escapades, but Kerr judicially treats it as a diversion and not the crux of his book. In Bernie’s bid to flush out the mole, Kerr expertly highlights the self-serving loyalties and back-stabbing skullduggery that afflict the preservation of power, not to mention the bravery of the oppressed and the risks they are prepared to take to loosen the tight stranglehold of the oppressor.

Along the way Bernie falls in love with the beguiling Arianne, who goes some way to assuaging his suicidal thoughts brought on by the wholesale slaughter he was privy to on the Eastern Front. Kerr is quick to assert Bernie’s credentials—the only good cop in Nazi Germany, and one who refuses to join the Party—and the black moods and burgeoning romance reinforce his humanity. His skewed morals render him all the more interesting, and each audacious display of insubordination towards Nazi top brass has us cheering him. The real proof that Bernie Gunther is Philip Marlowe’s heir is the barrage of dry one-liners. He visits a bar in Berlin playing bad jazz, a joint that “needed a coat of paint and a new carpet, but not as much as I needed a drink and a set of earplugs.” He looks at the drinks card—“The prices felt like mustard gas on my eyeballs, and when I’d picked myself off the floor I ordered a beer.” The wisecracks work best when they insult: A Gestapo officer is in his way, “blocking the sun, as was their habit”; it’s not the Jews who should wear yellow stars but Hitler, “and sewn just over his heart – assuming he had one – an aiming spot for a firing squad.” And as ever, Bernie regales us with a colorful array of Berlin slang. He utilizes his vitamin B and rubs shoulders with cauliflowers, footballs, bulls, and joy ladies.

But Kerr knows he has to return to the darkness to keep his account plausible, and after stomaching an autopsy, a torture scene, and a wave of brutal reprisals, we are reminded that Bernie, for all his insolence, is still a captive in the cruelest of dictatorships. Sometimes Kerr’s moments of sobriety are tiny, blink-and-you-miss-them strokes. In one scene Arianne urges Bernie to visit Dresden, as it is safe—“I don’t think there’s ever been an air raid.” Later, Bernie leafs through Heydrich’s diary and finds among the upcoming appointments “a December conference at an SS villa in Grosser Wannsee.”

Prague Fatale is authentic because Kerr can muffle the horror of this epoch in dramatic irony but he can also shout it out loud. Above all, this latest addition is clever and compelling, proving once again that the Bernie Gunther books are, by a long chalk, the best crime series around today.

—Malcolm Forbes

Derby DayBy D.J. Taylor416 pages. Pegasus. $25.95.

Perhaps the saddest scene in all of English literature is that of Catherine Sloper, poised in her parlor with bonnet in hand, learning that her beloved fiancé, Morris Townsend, has spinelessly commissioned her aunt to break their engagement. The couple has had a disagreement, but Catherine believes that “she had only had a difference with her lover, as other girls had had before.” Her naïveté in matters of romance has limited her vision, and it is Aunt Penniman who delivers the crushing blow:“We must study resignation,” said Mrs. Penniman, hesitating, but sententious at a venture.“Resignation to what?”“To a change of—of our plans.”“My plans have not changed!” said Catherine, with a little laugh.“Ah, but Mr. Townsend’s have,” her aunt answered very gently.It is not the most catastrophic of fates, but somehow it pains me the most—that tinkling little laugh of surety, followed by the delicate condescension of her aunt’s reply. Aunt Penniman has, in five words, untied the rope from the dock and set Catherine adrift in a storm.

In his newest novel, Derby Day, D.J. Taylor recasts Washington Square’s beleaguered triumvirate—Catherine, Dr. Sloper, and Morris—and reimagines the motives at play among those negotiating the late-Victorian social ladder. By removing love from the equation, Taylor redistributes agency among his characters, enlivening the bland Catherine and imbuing that classic triptych with more outright mischief and subterfuge than the subtle Mr. James would ever have allowed.

Derby Day coyly bends and twists “poor Catherine” into the nebulous Rebecca Happerton (née Gresham)—the distrusted and slightly-loved only child of a rather hard-hearted, wealthy, respectable old man. No “simpering chit” of a girl, Rebecca is fierce and steely, a woman whose own father cannot quite figure her out. Taylor folds Aunt Penniman’s meddling into Rebecca herself, a “sandy-haired,” “green-eyed” creature who lurks around the edges of the novel, taunting readers and other characters alike with her ambiguous motives. Mr. Gresham, the father, is a stodgy solicitor—a man who, much like Dr. Sloper, appears constantly befuddled at the very idea of parenting a young lady. The third figure of the group is Rebecca’s fiancé-cum-husband, Mr. Happerton, whose marriage to Rebecca is simply the first step in a series of calculated (often illegal) plans and decisions, all designed to bring about a personal financial windfall at the titular Derby Day at Epsom Downs.

The first Epsom Derby was run in 1780, and by the year of Taylor’s novel (ambiguously set sometime in the 1860s) it had become a social staple of the London summer. A short race of only 1 mile, 4 furlongs, and 10 yards, it attracted tens of thousands of spectators, who made the 15-mile journey from London to watch an event only a few minutes in length. The stakes could be tremendous, however, with thousands of pounds in winnings resulting from a single well-placed bet. Though other races attracted high-stakes gambling, the Derby was the largest and most prestigious horse race in the nation. Accordingly, as a man who makes his money from “discounted bills … commercial speculations … [and] the turf” it is also Happerton’s anticipated payday.

The details of Happerton’s Derby scheme are only gradually made clear—a plot device which serves to lure the reader ever deeper into a delightful tangle of subplots. What’s obvious from the start, however, is that the plan is wholly tied up in a particular horse, Tiberius, a beautiful black specimen. Happerton is obsessed with acquiring Tiberius, going so far as to carry a watercolor portrait of the horse to a lunch party and on his Venetian honeymoon. Unfortunately, Tiberius already has an owner, a Mr. Samuel Davenant of Lincolnshire, who is as keen to hold onto the horse as Happerton is to buy him. The complicated dealings of the two men (which are far too riveting to be revealed here) form the scaffolding of this fast-paced, well-conceived novel.

The household of Scroop Hall, Mr. Davenant’s estate, forms half of Derby Day’s bilateral narrative—there’s Mr. Davenent himself, a moon-faced gentleman down on his luck following a string a bad horse deals and a lawsuit gone awry (à la The Mill on the Floss); Mr. Glenister, the kindly, wealthy bachelor who emotionally and financially supports Mr. Davenant; and Miss Ellington, the perceptive governess to Mr. Davenant’s peculiar daughter. The other half are players in Happerton’s scheme—Captain Raff, Happerton’s grimy sidekick and a broken-down, greasy-chinned model of unrewarded loyalty; Major Hubbins, the celebrated and aged jockey; Mr. Pardew, the burgling genius, who returns to London for one last job; and of course, Rebecca, whose feminine guile is not to be underestimated.

What’s most enjoyable about Taylor’s book is that it honors its Victorian roots while avoiding the campy predictability of so much “historical fiction.” Happerton’s silhouette is a common one—a man of ambiguous ancestry who knows just about everyone but whom nobody really “knows,” he social climbs using the only faculties at his disposal, his wits and his charm. But after marrying a rich, lonely heiress, his moral compass swerves in reassuringly complex ways. While employing Capt. Raff to run his unseemly errands and hiring Mr. Pardew to, ahem, help raise some cash, Happerton also moves into his father-in-law’s home and begins to care for the ailing old man. He keeps a mistress, but also maintains genuinely admiring feelings for his wife. His criminal nature belies a morally ambivalent spirit. As Derby Day looms closer and closer, and Happerton’s increasingly complicated plans go further and further awry, his villainy turns almost tragic. Never a stock villain, Happerton embodies the spirit of the age—he is a man who will prove himself at any cost.

A model of modernity, Happerton struggles to create himself, assembling an identity wholecloth. Meanwhile, Taylor’s others characters fight to maintain the status quo in a quickly evolving world. Modernity is rushing in all around them, and Taylor ably juxtaposes his characters’ early 18th-century tendencies with the emerging desires of the late Victorians. Rebecca—a direct descendant of nobility—marries a common man, if only for the excitement. A victim of the waning governess trade, Miss Ellington must take a position at the crumbling Scroop Hall. Multiple characters engage in the burgeoning credit market, buying and selling their “papers” (notes of credit) in a manner eerily akin to the modern American real-estate economy. And Mr. Davenant, most tragically of all, cannot adapt, and thus loses not only his ancestral home, but his prize possession, Tiberius, as well.

Every character’s fate is wrapped up in Tiberius’s performance at the Derby. For some, financial promise or ruin lurks just beyond the finish line; for others, it’s pride or revenge or a sense of purpose. Each character is imbued with his or her own bit of pathos. As the narrative rushes towards Derby Day, Taylor ably plaits together the variant narratives until they coalesce in a brilliant depiction of Epsom Downs, complete with “pastrycooks and beer-sellers and roast-beef providers ... gentlemen in loud waistcoats and cockades in their hats ... swells in frock-coats with German dolls ... tiny, starved boys ... and butchers’ wives from Shoreditch, in vulgar ribbons and their stays out, enjoying the spectacle.” The Derby is a panoply of London, made visceral and real, skilfully crafted from the mind of one of Britain’s most talented novelists.

—Hillary Kelly

I Am An Executioner: Love Stories By Rajesh Parameswaran272 pages. Knopf. $24.95.

Dangerous, misunderstood creatures—a man-eating tiger, a wild elephant, and of course, the title executioner, to name just a few—populate Rajesh Parameswaran’s debut collection of short stories. I Am An Executioner offers a fiercely creative—and deeply morbid—vision of what it takes to stay alive. The struggle for survival dominates the lives of these characters; it’s finally their most feral instincts that carve their fates.

As the title suggests, where there is love, death is near. When Ming the tiger discovers he’s fallen in love with his caretaker, the accompanying flood of emotion leads him to maul the object of his affection. When the perpetually unlucky-in-love executioner’s newest wife spurns him, he brings her to prison to see his work, hoping the experience will draw them closer (spoiler alert: his plan backfires). For the alien who narrates “On the Banks of Table River,” death is simply hardwired into his species’ mating rituals: As soon as his wife gives birth, he kills her so that her body may feed their new daughter.

Parameswaran’s human couples don’t fare much better. The closing scene of “The Strange Career of Dr. Raju Gopalarajan,” (a story that won a National Magazine Award in 2007 for McSweeney's) leaves a desperate charlatan “doctor” and his cancer-stricken wife alone with a sharp scalpel and few options. In the story of Savitri, a suburban housewife who unintentionally kills her husband with her thoughts, Parameswaran sneaks in an added irony: Savitri’s mythological namesake is legendary for talking the god of death himself into sparing her husband’s life.

But these stories are more than well-executed variations on a theme. In some of these stories finest moments, Parameswaran patiently teases out the most tender, human impulses of his characters—from the classified agent who struggles with her urge to simply to tell her husband about her day to the single-dad alien who lies about his real job to spare his daughter from embarrassment in front of her Earthling boyfriend. Even the quack doctor, Dr. Gopalarajan, derives a real glimmer of joy from believing he has “helped, not harmed” a fellow being. Death may be inescapable, but life is still a tender thing to be savored.

Parameswaran’s ease with language gives stories like “The Infamous Bengal Tiger Ming” a particular pull. Seen through the blundering tiger’s eyes, the world of humans is a weird, messy, and fragile place. Take for example, Ming’s vivid description of what it’s like to eat the small child he’s just accidentally killed:

… I turned around and picked up the human cub. It took me just two bites to crunch and pop and slurp and swallow the whole thing, and I was crying as I did so. I had never felt so much love in all my life.

Parameswaran’s playfulness with language is a comedic asset as well, as in one scene in “Four Rajeshes,” when a pompous clerk describes a sudden burst of goodwill as “one of those moments when the electric current of instantaneous affection arranges in its circuit a haphazarad constellation of objective facts.” But the line between quirky and stilted is a thin one, and in more than one story, Parameswaran’s linguistic antics drown out the stories. In “Elephants in Captivity (Part One),” for example, the deliberately overwrought footnotes intended to be a wry distraction are simply tiresome.

Even if these stories are sometimes trying, they are without fail, brightly original, and despite his dark themes, there’s a real levity in Parameswaran’s writing. This is a world of many fools, but few villains—a world where tragedy and farce are plentiful but evil is debatable. Perhaps this is why it’s hard to take the collection’s obsession with death too seriously: for every death or disappearance in this collection, there’s a wink. The reader can rest assured that behind all the blood and viscera is a know-it-all having some fun. As the narrator of the last story in this collection notes on the book’s last page: “What gives life to the stories are the bodies at the end of them.”

—Mythili Rao