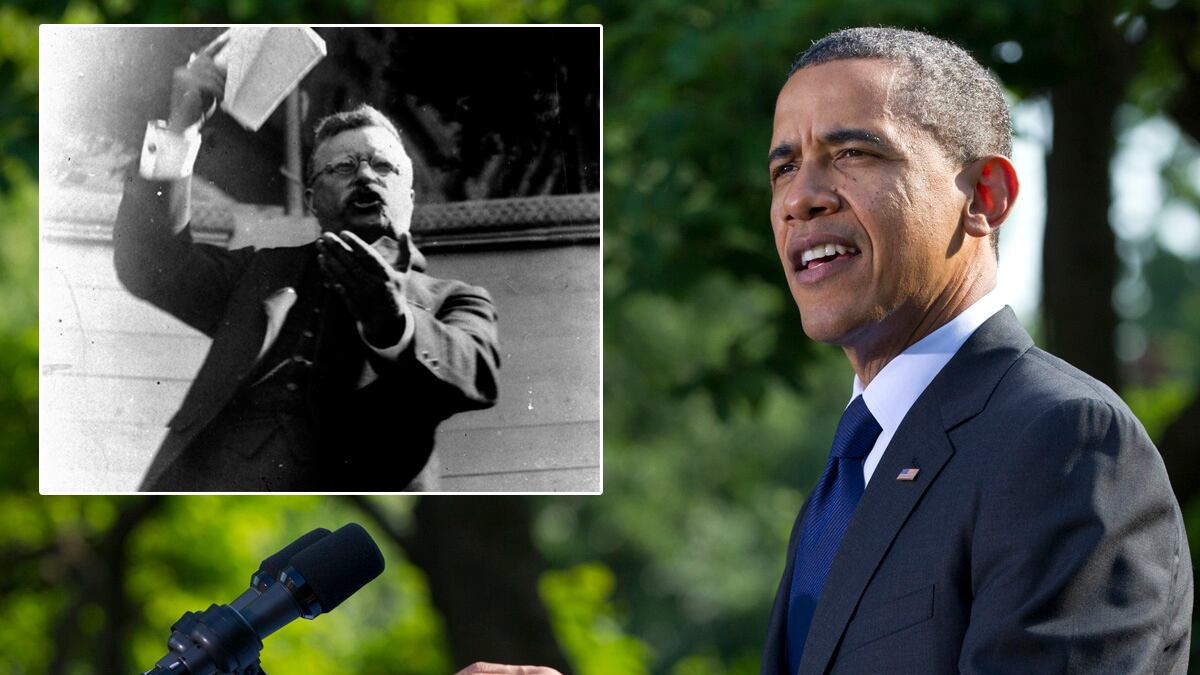

President Barack Obama’s bold endorsement of same-sex marriage calls to mind a previous instance when a sitting United States president took a stand on a charged social issue. On Oct. 16, 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt expressed his personal feelings about racial equality when he invited Booker T. Washington, distinguished educator and renowned African-American leader, to dine with the first family at the White House. Though blacks had built the White House, worked for most of the presidents, held political office, and occasionally met with the chief executive in his office to discuss business, not a single African-American had ever been invited to dine there.

The news that this longstanding color line had been crossed sent shock waves through the nation, provoking a flurry of inflammatory newspaper articles. “The most damnable outrage which has ever been perpetuated by any citizen of the United States was committed yesterday by the president,” was one indignant headline on the subject. There were scabrous political cartoons, fire-and-brimstone speeches, vulgar songs, and even a satiric, anti-Roosevelt/Washington film, with a white actor in blackface. The scandal escalated to the point where it ignited a storm of controversy, divided the country, and threatened to topple two of America’s greatest men—and all because Roosevelt did what he believed was right.

Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington were genuinely unprepared for the nation’s explosive reaction and struggled to deal with it. While the Obama administration is more sophisticated in anticipating—and deflecting—the country’s responses to controversial issues, there are valuable lessons to be learned from this historic conflagration. If Theodore Roosevelt were alive today, and could share a “President’s Club” moment with Obama, he might offer him the following advice about what to expect in the days, weeks, and years ahead.

Know that you have given the opposition a powerful weapon and they will happily use it against you.

In 1901, those who believed in racial equality saw the Washington/Roosevelt dinner as a giant step forward and a cause for celebration, but their opponents, mostly Southern Democrats, were equally celebratory. Their mission was to make the ever-popular Roosevelt, a Republican, unpopular, and the good news was that the president was doing their work for them. Senator “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman of South Carolina told his fellow Democrats, “Use it for all it’s worth,” urging them to act quickly and viciously, and they complied, spreading the word that “both politically and socially, President Roosevelt proposes to coddle descendants of Ham.”

Your endorsement of gay marriage may actually make life harder for members of the LGBT community.

News of the White House dinner provoked a wave of rampant violence and racism, especially in the South. The aforementioned Ben Tillman and extremists like him used the dinner to widen the existing divide between the races. “The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that n----- will necessitate our killing a thousand n------ in the South before they will learn their place again,” Tillman announced to his approving constituency. Booker T. Washington, the most visible African-American in the country, received numerous death threats, and blacks throughout the South were vulnerable to bigots who felt compelled to take a vehement stand on the issue of racial equality.

You will be surprised by how long the controversy surrounding your declaration will endure.

Roosevelt wrestled with Big Business, solved labor disputes, negotiated international treaties, and saved football. But the fact that he hosted that dinner would come up again, and again, and again. Immediately before the 1904 election, a clever Roosevelt supporter tweaked history in an attempt to make the incident more palatable. He suggested that the meal in question wasn’t a sit-down dinner with family, but an impromptu business lunch. The hope was that some gullible Southerners would swallow it and decide that Roosevelt wasn’t so bad after all. It worked—to a degree. Still, in 1905, when a student in Washington, D.C., was asked to use the word “debased” in a sentence during a vocabulary lesson, he thought for a moment before writing on the chalkboard, “Roosevelt debased himself by eating with a n-----.”

The road ahead will be rough, but chances are you will be fine in the end.

Democrats tried to use the controversial dinner to prevent voters from supporting Roosevelt in the 1904 presidential election, but to a large degree they were preaching to the converted. As political humorist “Mr. Dooley” pointed out, “Thousands of men who wouldn’t have voted for him under any circumstances have declared that under no circumstances would they vote for him now.” Roosevelt won the presidency and his opponent, the forgettable Alton Parker, was said to have lost the election by a landslide. More important, Roosevelt’s bold commitment to the advancement of civil rights at the White House dinner table was meaningful to him. “It will all come right, in time,” he wrote to Booker T. Washington, “and if I have helped by ever so little ‘the ascent of man’ I am more than satisfied.”