For as long as she can remember, Leslie Maitland has been rummaging about in the past, fascinated by her mother’s haunting memories of a long lost love.

Ten years ago, those tantalizing recollections became a mission—the slim, elegant, former New York Times reporter took off to Europe to ferret out the details of those compelling family histories.

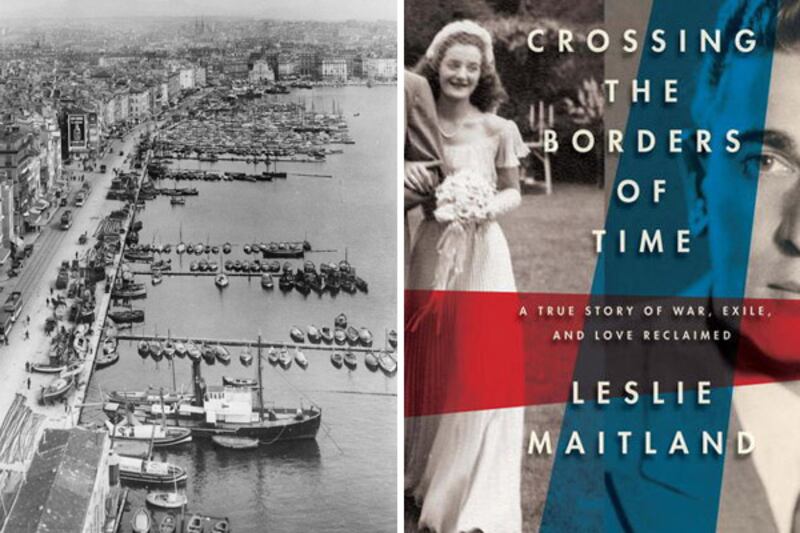

The result is the meticulously researched Crossing the Borders of Time, an absorbing true account of romance, resilience, and survival during the years leading up to and during World War II, set against the backdrop of the Holocaust and the harrowing social history of mid-20th-century France.

“I always wanted to tell my mother’s story,” says Maitland during an interview in her suburban Maryland home. “I had been mesmerized all my life by her tales of love, war, and escape that played out like a movie before my eyes.”

Her mother, Janine, now an effervescent 88, was a desperate 18-year-old German Jewish refugee in 1942 when she fled the Nazis with her family on one of the last ships allowed to leave Marseille. They slipped out under the wire—two weeks later the deportation of Jews to Auschwitz began.

At the dock, Janine was forced to part from the love of her young life: Roland, a 21-year-old Catholic Frenchman whom she adored and had sworn to marry. Her tortuous exile began in Cuba, where the family was interned in filthy conditions in a hidden camp for six months before they were allowed to move to Havana. From there, they finally migrated to New York, where they settled. But Janine’s father hid messages from Roland, who was frantically trying to find her. He disapproved of the couple and managed to keep them apart.

With no prospect of reconnecting with her first love, Janine married a dashing American, Leonard Maitland, whom his daughter describes as “a dynamic Rhett Butler.” It turned out to be a troubled and difficult union. Leonard became an obsessive acolyte of Ayn Rand and also indulged in a series of infidelities.

Meanwhile, Janine continued to yearn for Roland, sharing her longing with her daughter. The two forged such a close bond that when the author went to college, she sent a Mother’s Day card to Janine saying, “On the day you became a mother I entered life to mirror your life through my eyes.”

Their most extraordinary journey began as a piece for The New York Times entitled “Bittersweet.” In 1989 Maitland, her mother, father, and brother, Gary, traveled to her mother’s birthplace, Frieburg, Germany, on a pilgrimage of remembrance and reconciliation. Meeting Janine’s lost relatives, friends, and playmates was an indelible experience for the author.

They decided to return the following year, but when the time came, Maitland’s father had been hospitalized and the others dropped out. So she went on her own, retracing her mother’s footsteps from Germany to France. Crossing the border, Roland flashed through her mind. “The light bulb went off,” she recalls. “I had no intention of writing a love story. But it was such a mythological idea. Finding him would be a fairy tale.” It would also be an act of daughterly devotion. Like all good reporters, Maitland searched a local phone book and managed to locate Roland’s sister Emilienne, who invited the American to her home. Feeling anxious—her mother knew nothing about this venture—and fearful she might be betraying her ill father, Maitland rang the bell.

Roland’s sister welcomed her warmly. She said her brother had tried to contact Janine after the war. He was married and living in Canada. Then, miraculously, from a bookshelf, Emilienne produced Janine’s autograph book, her most prized possession, which she had given Roland as a keepsake when they said their last goodbyes. Roland had left it with Emilienne when he crossed the Atlantic.

Suddenly, in the middle of our interview, Maitland gets up, goes into her study, and brings back an arm full of faded, fragile documents—old photographs, letters, transit visas. Among them was that treasured autograph book, still wrapped in its original, tattered, black paper cover. It was filled with childish drawings and tributes in both German and French. Some were Walt Disney cartoons. The watercolors were still remarkable vivid.

“I’m an incredible collector of family memorabilia,” she says, recalling how her parents, during their peregrinations, were often forced to leave most belongings behind, but always held on to their personal records in a battered brown valise. “It’s a way of holding on to the people you love. I’m glad I saved everything. It helped me enormously in all my research.”

Maitland returned from Europe and told her mother about finding Roland. Janine was shocked and dismayed. “I hope to God you didn’t say I sent you,” she exclaimed. She was too timid to reach out to Roland, even though she had been given his address and phone number.

Shortly thereafter Leonard Maitland died, and within three months—50 years after they separated—Roland came back into Janine’s life.

He made the first call. “Bon soir, Janine. Is it really you?” he asked in his Alsatian-accented French. According to Maitland, Janine’s “knees trembled and the decades disappeared. The world began to glimmer with endless possibilities.” After almost a year of daily phone calls, Janine bought a ticket to Montreal and rekindled a romance that lasted for 15 years. Roland never divorced; he simply told his wife he was going on business trips as he flew back and forth between Montreal and Washington, D.C., where Janine now lived.

When they were together, they never wanted to go to out to a movie or to the theater. They were happiest talking and reliving the lost years. The most emotional and poignant moment of their reunion was their return to France, to the separation point on the pier in Marseille. “Don’t sail away from me again,” whispered Roland.