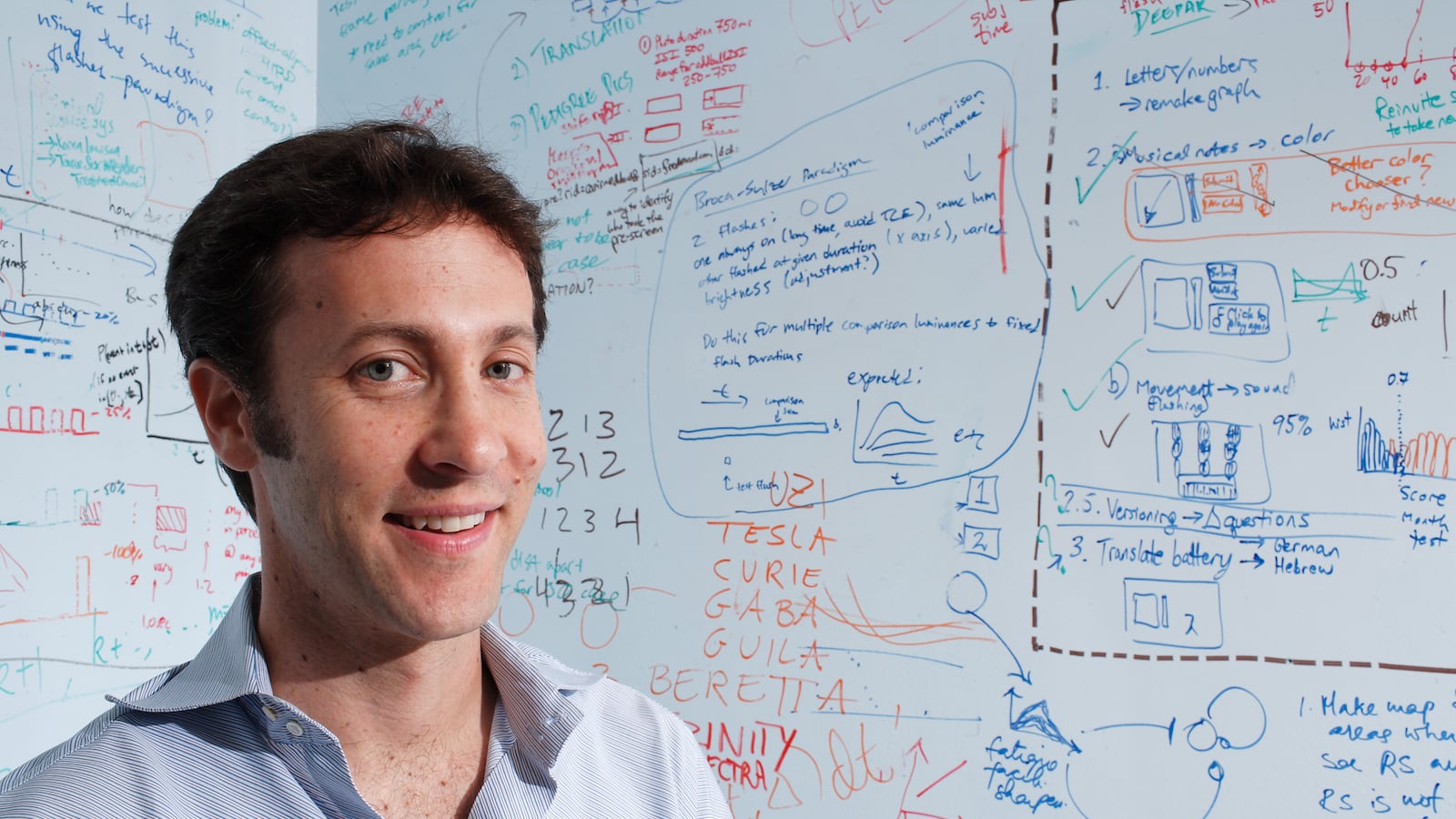

David Eagleman is a professor of neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine running his own lab, a successful author, a dynamic lecturer (with a popular TED talk on his resume), and his reputation was sealed when The New Yorker profiled his unusual work on the brain’s perception of time. His latest book, Incognito: the Secret Lives of the Brain, is out on paperback this week. Eagleman speaks about accidentally founding a worldwide movement, why being high-profile can be an occasional liability, and how being featured in The New Yorker changed his life.

Where did you grow up?

At the foot of the Sandia Mountains, just outside Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Where and what did you study?

As an undergraduate I majored in British and American literature at Rice University. I then went on to a Ph.D in neuroscience at the Baylor College of Medicine, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at the Salk Institute.

Where do you live and why?

Houston, Texas. I was recruited back to the Texas Medical Center here after my postdoc. As the largest medical center in the world, it provides fertile ground for a research lab in terms of technology, patient populations, and collaborators.

Of which of your books or projects are you most proud?

Sum. Because it’s the most unusual.

Describe your morning routine.

My consciousness coheres in stages. While it’s still in an intermediate stage, I pick up my phone and check the text messages I received during the night, then my email, and finally my calendar for the day. Collectively, those exercises fill me with enough panic to launch out of bed and hit the day at full tilt.

What is a distinctive habit or affectation of yours?

I always bounce my legs when I’m sitting. I once lived on the second story of an old building in England (my junior year abroad), and my leg-bouncing hit the resonance frequency of the house and caused things to fall off the shelves below.

Do you have a writer friend who helps and inspires you?

Several writer-friends inspire me: Michael Chabon, Art Spiegelman, Neil Gaiman, Jonah Lehrer, and Susan Orlean, to name a few. I’m also in a small writer’s group in Houston—we’re currently writing a screenplay together—great fun.

How does your week look, in terms of balancing your lab, academic work, and popular writing?

My lab and academic work fill my day from about 9 am to 7 p.m. Then I zoom out the lens to work on my other writing.

How did the recent New Yorker article change your career, if it is not too early to tell?

Within academia, my friends joke that it may be more a liability than an asset. But in the broader world it has had a lovely effect. It turns people on to a very specialized subworld—the study of time perception—which most people didn’t know existed, and which, for some, has unexpected appeal.

What is your favorite course to teach?

“Neuroscience and the Law.” It’s a course I’ve built from scratch over several years, and the students are grad students, med students, law students, undergrads, lawyers, judges, and ethicists. That makes for shockingly rich discussion and debate. The material is where the rubber really hits the road in terms of applying the lessons of modern neurobiology to the way we think about building social policy and living together.

You are particularly good at making complex ideas accessible to the widest possible audience. Not all professors can do this. Is there a conscious translation of complex idea to accessible analogy that goes through you, or would you explain your approach in another way?

I just follow the rule I tell all my students: if you can’t explain it to an eighth grader in a way that he/she would understand it, then you don’t understand it. As a corollary, one must understand the importance of narrative. Our brains have evolved to care about story. If you want to penetrate the brain of a listener, wrap the information in things they care about.

You have written fiction and non-fiction, as well as academic texts. How does your approach differ between genres?

In academic texts there is a particular landscape of facts that needs to be surveyed. In nonfiction one chooses a particular path through that landscape, taking the reader on a special journey of your choosing. In fiction one takes off into the third dimension.

Describe your writing routine, including any unusual rituals associated with the writing process, if you have them.

I wish it could be called a routine; instead, it’s a scrambling for little windows of time wherever I can find them. Usually on airplanes and in hotel rooms.

What is guaranteed to make you laugh?

My wife. One of my life’s greatest pleasures is cracking up with her.

What is guaranteed to make you cry?

Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes. More generally, any true story in which a child is treated badly.

What phrase do you overuse?

“It turns out that …”

What is the story behind the publication of your first book?

Several years of rejections from publishers and agents who loved the book but couldn’t figure out what do to with it. Followed by a moment when someone took a chance and everything changed.

Was there a specific moment when you felt you had “made it” as an author?

Well, I had a funny moment a few years ago while signing copies of Sum in a bookstore in London. Making conversation, a friend of mine asked the sales clerk if he had read the book yet. “Nah,” the clerk said, “I don’t read things that are too popular.” That struck me as an interesting turning point, because (at least from the clerk’s point of view) Sum had gone from being a left-field, indie, take-a-chance book to something everyone was discussing.

What do you need to have produced/completed in order to feel that you’ve had a productive writing day?

A nugget that captures some truth. It can be as short as a sentence.

Please recommend three books (not your own) to your readers.

Olaf Stapledon ‘s Last and First Men: science fiction written in 1930. It describes humans 2 billion years into the future. Boundless imagination.

William Faulkner’s The Bear. I bought this book for 50 cents at a garage sale when I was 17. The combination of storytelling and wordsmithery blew my socks off. I immediately became an English major.

Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. A story about the immigrant experience told only with drawings.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

Write exactly what you would want to read, what you wish someone else had written.

Tell us something about yourself that is largely unknown and perhaps surprising.

Without meaning to start a movement, I started a movement. It’s called “possibilianism,” and it’s taken off around the globe. Every week I get letters from people worldwide who feel that the possibilian point of view represents their understanding better than either religion or neo-atheism. The major newspapers in places like India and Uganda have written large spreads on the idea. I’m looking forward to seeing how it continues to evolve.

What is your next project?

I have three. First is a textbook on cognitive neuroscience for undergraduates. Second is a book on brain plasticity—that is, how the brain constantly reconfigures its own circuitry. Third is a popular science book on the perception of time.

Read more of our “How I Write” series: