Earlier this week, a government-sponsored task force created a stir when it recommended against routine PSA (prostate specific antigen) screenings, the most common and widely accepted method of detecting the presence of prostate cancer for nearly two decades. Having considered the evidence from two large-scale trials, the task force concluded that the PSA screen can too easily turn up false positive results, sending men down a road of risky and often unnecessary treatment.

“There’s been a lot of hype and overpromise about the value of PSA,” says Otis Brawley, head of the American Cancer Society. “I know that the harms to the population are greater than the benefits at this juncture.”

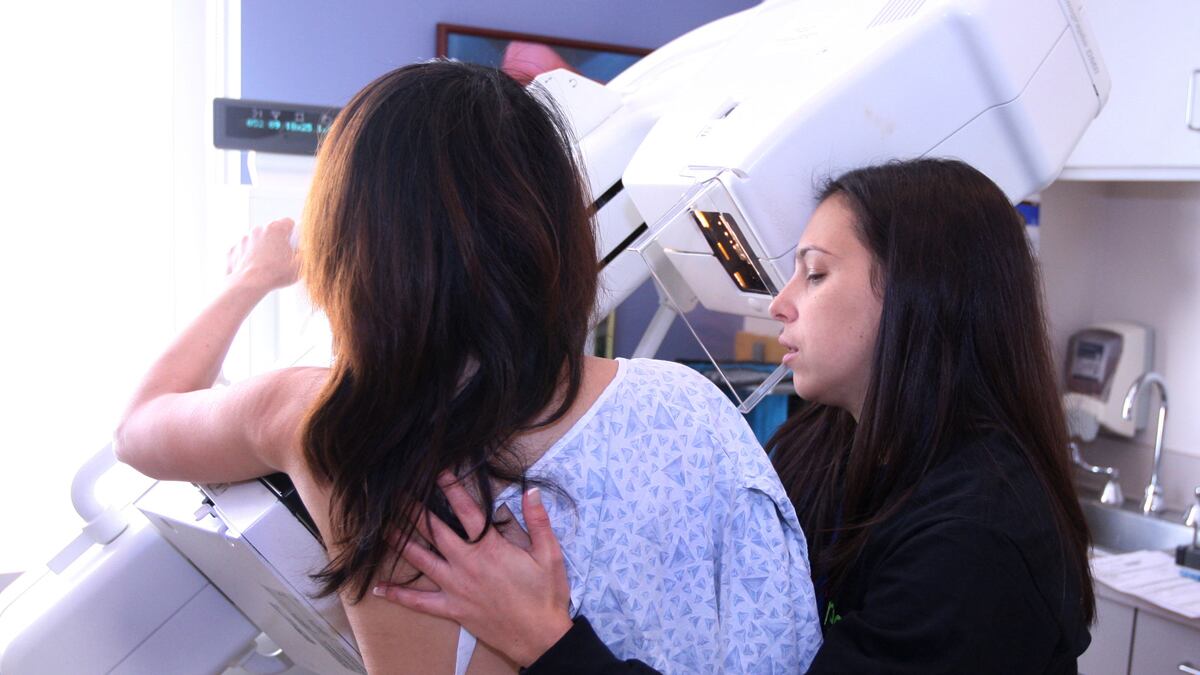

The furor over the change in the PSA guidelines echoes a similar controversy in 2009, when another government-sponsored task force announced that routine mammograms should no longer be given to women in their 40s, because there was no evidence that women in that age group stood to gain from it.

The mammography downgrade, like the PSA ruling, provoked furious opposition among patients and breast-cancer advocates of all kinds, to an extent that surprised even the task force itself, says its chair, Diana Petitti.

Regardless of the controversies, it’s hard to know what effect these recommendations actually carry. Medicare still covers routine mammograms and has announced that it will continue to pay for PSA screens as well. Data on whether fewer women are getting mammograms since 2009 are not yet available.

But what both sets of recommendations demonstrate is a fundamental uncertainty—among doctors and patients alike—about preventing harm versus causing it. To some medical professionals, the prevalence of routine mammography and PSAs is indicative of a larger problem in American health care: expensive procedures that research has shown to have little or no benefit and which can carry significant risks, are widely performed by well-intentioned doctors.

The debate is anything but academic. Opponents of the new PSA screen guidelines fear a resurgence of deaths from prostate cancer, which have been on the decline since the ’90s. The tone of dissent has been particularly strong among urologists in the last week, many of whom have expressed outrage at the nature of the evidence the panel used to make its decision.

However, says Shannon Brownlee, director of the health-policy program at the New America Foundation, because urologists often see patients with advanced prostate cancer, they might struggle to see the full context of the issue objectively.

“I understand their emotional response to the power of this disease to cause suffering,” she says. “But what they don’t see is the power of medicine to cause suffering. And it’s really important that we be able to see both.”

Avoidable care is an issue the medical profession has been aware of for decades. But until recently, physicians who have tried to talk about the problem have not found a receptive audience, even among fellow physicians. In a recent interview with The Daily Beast, Dr. Bernard Lown recalled a lecture he delivered in New York City 30 years ago to 600 physicians (including a “good sprinkling” of heart specialists, he said). Lown, whose International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War won the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize, asked how many of the doctors in the room who ordered coronary bypass surgery had told their patients the procedure would not prolong their lives. Most of the doctors bowed their heads a bit and looked about. Nobody raised a hand. The paramount motive for unnecessary bypass surgeries was profit, Lown explained in the interview at his home in Chestnut Hill, Mass. But another key component, he said, was cultural. “It’s the way we train people in medical school and the way we indoctrinate them in hospitals. It’s the way you want to do something that is decisive. When you’re a young person, you cannot tolerate uncertainty, and when you get older you learn that you have to live by it,” Lown said. “The bypass, the stent, is a definite answer to a problem, you have it done and it’s over, it’s ended—that ain’t so. A patient still has coronary disease, he still has risk factors, and the lifestyle that brought him to the doctor in the first place will bring him to the doctor a second and third time.” Research today continues to confirm what some doctors recognized decades ago: widespread, expensive procedures exist that show no benefit for the patient. The price tag for hospitalization after a coronary-disease diagnosis is more than $16,000 (PDF), and more than 400,000 angioplasties are performed each year on stable patients. But a recent article in the Archives of Internal Medicine shows that for patients with stable coronary-artery disease, the current medical therapies—such as aspirin, beta-blockers, ACE-inhibitors, and statins—don’t reduce death rate, chest pain, and other cardiac events any better when combined with stent angioplasty. It is the first research to look at the outcomes of patients who received modern angioplasties. In short, the study found that adding an invasive, expensive procedure to prescribed therapy regimens has no apparent benefit. According to the study, up to 76 percent of stable patients can avoid angioplasties, with nearly $10,000 per patient in lifetime health-care cost savings.

Research has also shown that lifestyle changes can help regress coronary disease, but there is a dearth of major research on whether doctors encourage lifestyle changes—and, importantly, whether patients follow through with their doctors’ lifestyle recommendations for reducing heart disease.

The way doctors are paid is one reason why avoidable procedures persist. An extra hour talking to a patient, Lown and other medical professionals say, can effectively elucidate the root cause of an ailment. But that pays far less than performing a procedure. Under the Medicare fee-for-service system, doctors get paid for action, not attention. As a result of this system, young doctors have less financial reason to enter primary care—the first line of defense against avoidable procedures—and turn to specialty areas, where they can earn on average, an extra $3.5 million over the course of a career, according to Dr. Allan H. Goroll, Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Another culprit is what Dr. David H. Newman, director of clinical research in emergency medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, calls scienciness, the illusion that a sophisticated new procedure or technology should be used simply because it exists. Take the clogged artery. For a patient having a serious heart attack, clearing the artery can save a life, Newman says. For everyone else, it doesn’t. “It’s exactly the same problem as PSAs and mammography,” Newman says. “The scienciness of looking inside a breast tissue, or of seeing an antigen that is supposed to be specific to the prostate in the blood, or of opening an artery—that scienciness is powerful—and when we look at the science, at the benefit to the human, we are finding that none of those things seem to achieve what we wanted them to.” Doctors like Newman and Lown may be gaining a more prominent voice in the national conversation. The Choosing Wisely Campaign and last month’s Avoiding Avoidable Care conference in Cambridge, Mass., sponsored in part by the Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, indicate there is an appetite among health professionals to move away from expensive, unnecessary procedures—and the driver for that appetite comes down to dollars and cents. “The conversation has switched to costs,” said Dr. Vikas Saini, the president of the LCRF. “If you want to talk about the deleterious effect of taxes and the economy—the health-care system is the biggest taxation system in the world. A lot of it is avoidable, unnecessary, and to that extent it represents a real problem.”