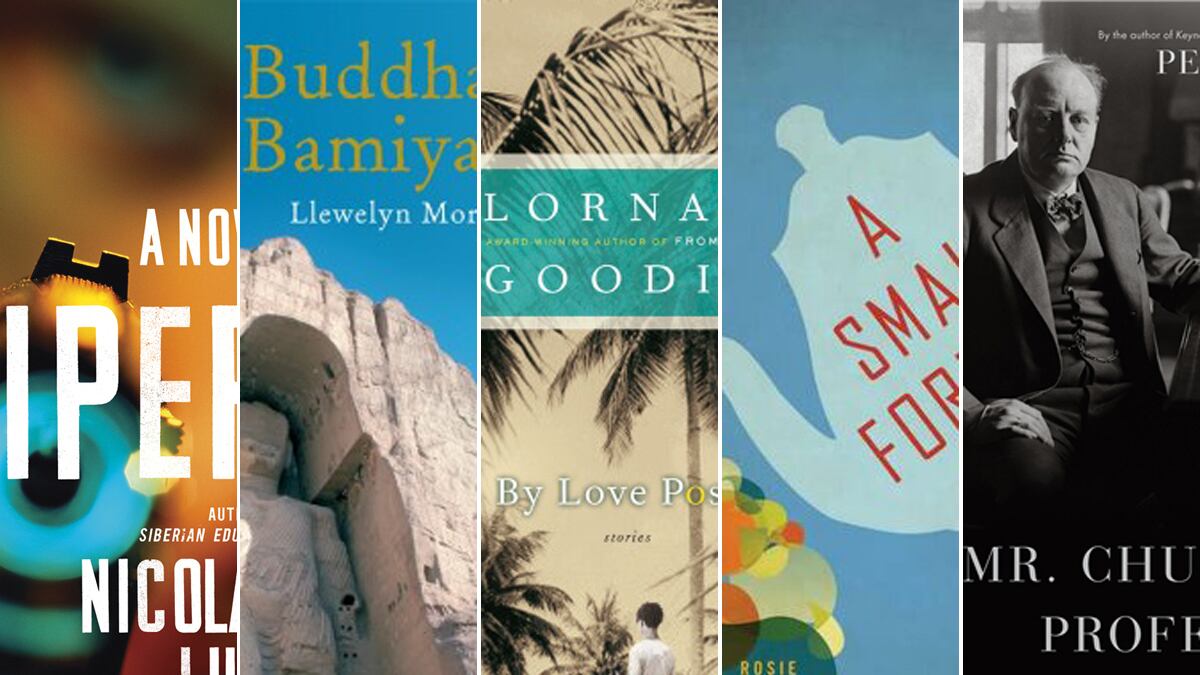

By Peter ClarkeChurchill never made any money except with his pen, and his 34-volume output was extraordinary even for a full-time writer. Except he was the world’s leading statesman, too.

Who was Winston Churchill? A man of politics, sure, a leader to help England “keep buggering on” in the darkest hour. The historian Peter Clarke never makes the case that Churchill was first a writer—no, his calling was politics, for that was what all Churchills did. And no, Clarke did not confuse the English Winston Churchill with the American Winston Churchill, who also wrote books—novels that sold well, so that the Brit had for a time “received from many quarters congratulations on my skill as a writer of fiction” and thought it due to “a belated appreciation of the merits of Savrola,” his only novel.

As for Churchill’s profession, there was nothing else besides his writing, for “I’ve never had any money except what my pen has brought me.” And what a load his pen had to carry, for the man inherited from his mother indulgent needs. “We are, both you and I, equally thoughtless, spendthrift and extravagant … We are damned poor,” he wrote her in 1898.

The result was a formidable literary output: the two-volume biography of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, and of his forebears, the first Duke of Marlborough, set to four volumes; his magnum opus, the monumental four volumes of A History of the English-Speaking Peoples; his World War I memoirs, titled The World Crisis, ran to five volumes; his The Second World War ran to six; My Early Life a (comparatively) miserly one. If you threw in the republishing of his journalism and eight volumes of his speeches, his authorized collected works runs to 34 volumes.

The topic had already found a charming few pages in the fantastic Aspects of Aristocracy by David Cannadine, who declared: “Even for a full-time writer, Churchill’s output would have been remarkable. For a man whose main career was politics and government, it was quite extraordinary.” The late William Manchester also peppered Churchill’s true profession in his definitive and meticulously researched biography, The Last Lion, of which the third and final volume, Defender of the Realm, finished by Paul Reid, will be published in November. And David Reynolds contributed another excellent book on the subject showing how Churchill in a sense refought the Second World War in writing his history of it. Clarke goes further than they do in justifying Churchill’s 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature, rejecting Swedish author Sigfried Siwertz’s assertion, at the presentation of the award: “Behind Churchill the writer is Churchill the orator.” “The opposite would be more accurate,” Clarke writes, claiming that A History of the English-Speaking Peoples “was in fact the seedbed of much of his memorable wartime oratory.” Longer quotations from and deeper analysis of the prose of History would have helped his case, especially to counter the persuasive charge that the statesman wrote such admiring and uncritical portraits of his father and ancestor because their opportunism, vanity, and power-hunger had been associated with Winston as well. What Churchill’s literary motives were have entered the realm of speculative opinion, with the facts hardly able to strongly support one view or another. But we hardly need to be convinced that the Caesar/Cicero of wartime England was a serious writer, and Clarke’s brisk volume is a welcomed companion to Cannadine and Reynolds—and bring on Manchester.

By Llewelyn Morgan Two faceless giants stood for 1,400 years on the side of a rock cliff in Afghanistan, ready to listen to passing merchants, an inn for the spirit. Then they were destroyed by the Taliban.

Today, culture can seem little more than thinly disguised consumption. Film, music, art, and literature depend on customers, and architecture obviously has its utility. Museums charge admissions, and monuments bring tourists. Occasionally, there’ll be fights over the ownership of ancient stolen artifacts, with countries drumming up big plans for returned works. But the Buddhas of Bamiyan hardly brought in any money for anyone. The two faceless giants stood for 1,400 years on the side of a rock cliff in a fertile valley in what is now Afghanistan, having witnessed the passing of merchants, monks, and armies on that great ancient highway, the Silk Road. Few pilgrims made a point to journey to them: the road did not lead to them; it passed right in front of them, a highway truck stop.

Which makes the destruction of the Buddhas ever more tragic. Here were two silent friends, standing, not sitting, ready to listen and spring to duty lest travelers wished to confide in them in the middle of an arduous journey. They were lonely servants providing an oasis in a long, desert path. In March 2001, they were dynamited and demolished, on the orders of Mullah Omar, the spiritual leader of the Taliban.

What are the functions of a monument, a unique cultural artifact? What’s at the intersection of art, religion, tradition, propaganda, and global conflict? What was the big deal with these semi-forgotten giants that they should suffer humiliation and death? The excuse was that they were idols, but the rest of the Taliban didn’t exactly support the order. It was not an Islamic act. There were resentful claims and justifications from Omar’s people that the West had never paid attention to Muslims, and this was payback from what sounded like a shunned girl-crush. The richly enjoyable Oxford lecturer Llewelyn Morgan takes all of those rationalizations into consideration, but goes much, much further, mostly back in time, to unearth the practically schizophrenic thousand-year-old personalities of the pair of Buddhas, and how Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, Chinese, Mongols, Hazaras, Englishmen, Hindus, Persians, and even the Greeks have hacked at them, and chiseled into them a piece of themselves. Always entertaining and never too academic, Morgan has done what no others have been able to do, including UNESCO, Japan, and Switzerland, who have all pledged to rebuild the Buddhas. He brings them to life again, and let them tell their tales, still etched in stone, words in air.

By Rosie Dastgir A novel about the Pakistani-British experience in England, taking the opposite approach from the maximalist Zadie Smith, preferring the small things.

Speaking of a confluence of cultures, A Small Fortune features a man originally named Haaris but now called Harris, who moved from Pakistan to England in the 1970s. His Muslim beliefs pull him in unexpected ways when he gets divorced and comes into a settlement of some £53,000, the small fortune of the title. Or is it? The way to enjoy this debut novel is to not focus on what Harris does with the money, but by observing the descriptions that Dastgir makes of the little things in life, from food (“all those wretched tin cans, the leathery joints of meat”) to dates (Harris courts a recently widowed Pakistani Shakespeare scholar named Farrah, and goes to the Royal Observatory with her). The approach is far from the creative strivings of White Teeth, which went the maximalist route, as Zadie Smith tried to simulate the complex Bangladeshi-British experience. The “small fortune” plot is Dastgir’s own way of maximizing the efficacy of her own drama, and there are moments when she reaches too far.

But the times when money, generational differences, and emotional FedExing aren’t brought up are when the book feels far more earnest than Smith’s. The way Harris sees his own actions through his own eyes, as he drives up and down much of England and goes about worrying about her daughter, Alia, gets to the stem of his brain. It would have made a lovely longer short story or small novella, but one can hardly fault Dastgir for wanting Harris to be bigger, and to spring him onto the world scene, even if she comes up just a tad short. As it stands, it is already a rather handsome small fortune.

By Lorna Goodison

A Jamaican-American poet’s collection of short stories, depicting colorful personalities and the words flung between powerful characters.

One can’t imagine any excerpt of A Small Fortune appearing as one of the short stories in By Love Possessed, a collection of colorful vignettes by the Jamaican-American author Lorna Goodison. You can always hear Harris’s meek, apprehensive voice inside his head, whereas Goodison deals with the physical world and the words flung between her powerful characters—she’s scoring a dance. Her performers fall passionately in and out of love, and the title story tells of a tall, skinny, “dry up” woman, Dottie, taking in Frenchie, “easily the best-looking man in Jones Town, maybe in the whole of Jamaica,” who had a “glorious temper.” Goodison reveals the hurt in Dottie’s heart by precisely leaving her feelings unsurveyed. (“But he was gone, so what was the point.”) It’s an addictive game to play, paying attention to the silences in the songs. The verbal precision hints at the fact that these are a poet’s stories, and Goodison is a poet, coached by the Nobel Prize–winning poet Derek Walcott. If the book suffers from an occasional humidity and surface-oriented vitality, it also draws from the virtues of a Walcottian humidity and surface-oriented vitality. A short story can be a very elastic form, and inhabit somewhere between a novel and a poem. By Love Possessed is what that realm looks like.

By Nicolai Lilin A direct, simple look at the Chechen war through the eyes of an elite sniper, based on the author’s own experiences.

There are two books within Sniper. One is a blunt memoir. Read in this way, Sniper is very much like Lilin’s first book, Siberian Education, about growing up among crooks in Transdniestria, which declared its independence from Russia in 1900, an act that was never recognized, and Lilin’s second book, Free Fall: A Memoir, which chronicles his time as a sniper in the Chechen war. The two works have a precision to them. Sniper has the same devotion to simplicity. Nobody can argue against the severity of conflict, or that you need few adornments in war literature.

But the second book, enveloping the first, is a novel. Reading the exploits of the elite sharpshooting regiment known as the “Saboteurs,” and how they “brought back trophies from every mission,” and why “it was true” that “the most dangerous people in urban combat were the snipers”—you can’t help but feel Lilin is flaunting it a bit. Lilin attempts to add a universality to the proceedings, as he “created a composite narrator whose experiences combine those of many of my friends.” Perhaps the language loses some finesse after being translated from Italian, by Jamie Richards. Yet even when Lilin’s hero is relaying his psychological struggles, the directness gains an air of aggrandizement, not to mention obviousness. Of course war is horrid. Of course one is constantly in danger of turning into a mindless killing machine. Of course brotherhood and survival becomes crucial. Of course returning home can be the hardest part.

My advice: think of Free Fall as a making-of, the result of which was Sniper. The lack of literary invention will not seem artless, but will feel rather precise, magnified, and clear—like looking through a sniper scope.