At Sargent Shriver’s funeral, Bill Clinton brought the house down.

When Clinton got up to deliver his eulogy on a cold Saturday morning in January 2011, all five of Shriver’s children, as well as Vice President Joe Biden, had already given moving remembrances, each more effusive than the last. The evening before, at the wake, George McGovern, Bill Moyers, Chris Dodd, and Steny Hoyer, among others, had delivered stirring tributes. The portrait of Shriver that emerged from these reminiscences was, even by the hyperbolic standards of the form, hagiographic. Here, we were told in anecdote after anecdote, lay a man who was not only great (he had founded the Peace Corps for his brother-in-law John F. Kennedy, served as the commanding general of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, reset America’s relations with Charles de Gaulle as ambassador to France, helped launch the Special Olympics—and was a decorated Navy veteran and a civil-rights pioneer to boot) but also manifestly good: he carried himself with unusual grace and humility, he exuded sincere hopefulness and good cheer in even the darkest of times, he loved his children and wife unconditionally, and he was the rare political figure whose moral compass remained ever unwarped by power or ambition.

So when, after all this, President Clinton stood up and asked, “Could anyone really be as good as Sargent Shriver seemed to be?” the church erupted in laughter. “I mean, come on now,” Clinton continued, milking the moment. “Every other man in this church feels about two inches tall right now.”

Tell me about it! I spent the better part of five years writing a biography of Shriver, and as inspiring as I found him and his life to be, protracted exposure to him and his accomplishments could sometimes be dispiriting and a little bit puzzling. To compare myself to him (an inevitable impulse, at least on occasion, when you spend five years immersed in someone’s else life) was to be plunged into instant despair at the gap between the greatness of his achievements and character and the relative paltriness of my own. More than that, I struggled with the mystery of Shriver’s relentless idealism and hopefulness in the face of the obvious darkness and tragedy of life. What accounted for his adamantine optimism?

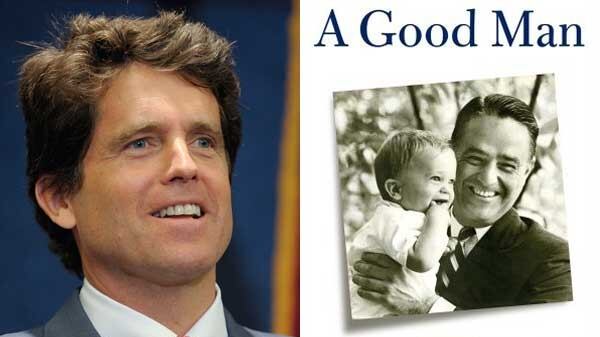

Mark Shriver is Sargent’s fourth child, and among the many treasures in his affecting new book, A Good Man: Rediscovering My Father, Sargent Shriver, is the revelation that he, too, struggled to understand his father’s fierce idealism, and that he sometimes staggered under the expectation that he live up to his family’s legacy of greatness. (I should say here that it was refreshing to be reminded that even Shrivers feel doubt and insecurity. Watching them frolicking on Cape Cod with their cousins, I sometimes assumed they must be immune to such feelings. Just look at them, I would think: those athletic good looks, that Kennedy hair and teeth and tan from their mother, that Shriver elegance and charisma from their father—not to mention the confidence borne of the long list of accomplishments each of them has rung up. I should say here, too, that I am hardly a disinterested observer: I don’t know Mark Shriver well, but I interviewed him for my book, and I gave him occasional modest research assistance with his, and he mentions me in it.) Mark was devastated by his father’s passing and was inspired by the occasion to try, as he puts it, “to solve the riddle of ‘Sarge.’” The result is this book—part memoir, part tribute to his father, part meditation on the difference between greatness and goodness.

Growing up the son of a public figure, in a house where busts of two famous uncles (JFK and RFK) gazed down upon him, Mark absorbed the lesson that as a member of the Kennedy family, you were supposed to be not a mere witness to history but a driver of it. “I had the fixation that comes with being a Kennedy,” he writes, “to be a great man on the big stage.” From an early age, his antennae were keenly attuned to every broadcast on what he calls the “Kennedy internal news channel,” which trumpeted the successes of his many siblings and cousins. “Any whiff of Kennedy competition spurred me to push myself as hard as I could,” he writes. (It says something about the intensity of competition among Shrivers and Kennedys that in family games of water polo, participants were encouraged to hold opponents under water to the point of near drowning.) As a young man, Mark ran for state office in Maryland (and won) because he “knew that politics was the way to keep up—rise, rise, rise, like a Kennedy should.”

But Mark sometimes felt crushed by the outsize expectations imposed on him as a member of the Kennedy clan—he writes of his “Kennedy claustrophobia”—and he struggled with abiding feelings of insecurity, the sense that was not living up to the family name. When he narrowly missed becoming a U.S. congressman, losing a close Democratic primary in Maryland in 2002, the defeat gnawed at him.

But Mark noticed that his father seemed not to be haunted by losses in the way ordinary politicians were. In the spring of 1976, when Mark was 12, Sargent Shriver conceded defeat in his race for the Democratic presidential nomination. During the campaign, Mark had loved having the Secret Service detail around. “Nothing was more fun for a boy than to throw a football or a baseball with athletic guys who were willing to give their lives to ensure his dad’s safety. They were heroes to me.” But then his dad conceded defeat, and just like that, the Secret Service detail was gone. “I will never forget that sense of loss,” Mark writes. “I felt abandoned by the greatest group of playmates a kid could ever ask for. It was like a punch in the gut. What had just happened? I learned that at that moment that fame, fortune, and adulation are gone the minute you’re out of politics.” And yet, Mark realizes in retrospect, for his dad, nothing had changed. What for most politicians would have been “an agonizing blow to their very being” was, for Sarge Shriver, a mere “blip on his cosmic radar screen.” Why? His abiding religious faith.

If ever there were an argument for the benefits of religious faith, it was Sarge Shriver. “Dad was joyful until the day he died,” Mark said at the funeral, “and I think that joy was deeply rooted in his love affair with God.” Sarge’s buoyant idealism—his exuberant soul—was inseparable from his deep faith. As a reluctant agnostic (I’d like to believe), I’ve never been able to muster either the sustaining faith of a Shriver or the dismissive contempt for religion of a Christopher Hitchens. But I was surprised to learn that even Mark Shriver, a devout Catholic, a believer who goes to Mass every Sunday, was in awe of the strength of his father’s faith. “Good God, to believe like he did,” Mark writes.

Sarge’s devout Catholicism made his ambition, as Mark puts it, more “cosmic” than “egotistical”—an ambition that drove him not toward amassing power for its own sake but rather toward power in the service of advancing justice and equality. This ambition made Sarge a Democrat. My wife—who consented to a first date with me 14 years ago pretty much only because I was writing a book about Sargent Shriver—observes that in political life today there are two kinds of Catholics: Shriver Catholics and Santorum Catholics. (She laments that of late the latter have become more prominent than the former.)

When Sarge began his decade-long descent into Alzheimer’s, Mark was gutted. He recounts a series of painful scenes (including watching his father, a lifelong Baltimore Orioles fan, struggle to fill out a baseball scorecard) and wrenching choices, none more difficult than the decision to let Richard “Rags” Ragsdale go. Rags had first come to work for Sarge in 1966, a driver assigned to him by the federal government, but before long was working for the Shriver family as jack-of-all-trades and field manager for all the myriad Shriver family operations. A profane Navy veteran (“Goddamn, Markie,” he’d say, “your mother is working my ass to the bone”), he was forever either quitting or getting fired and then showing up for work before dawn the next day as if nothing had happened. This went on for nearly 50 years. He became a second father to Mark and the other Shriver kids—and, Mark says, he became Sarge’s best friend. The two them, Sarge and Rags, spent countless hours in the car together; by the time they were both in their 80s, they had attended Mass together tens of thousands of times. So when it was determined that Sarge, advancing more deeply into Alzheimer’s, needed specialized round-the-clock nursing care that Rags was not equipped to provide, Mark made the heartbreaking decision to let Rags go. Rags wouldn’t go easy. “Markie,” he said, “when your grandma Shriver was on her deathbed, she asked me to take care of your dad until he died—or I died. I promised her I would, and I am not going to stop now.”

But Rags did go, and in a tragic-ironic turn, he, too, was soon stricken with Alzheimer’s, declining much more rapidly than Sarge did. The Shriver kids would get the men together for lunch sometimes, but the two old friends, minds beclouded by disease, mostly sat in stilted silence. Rags died in July 2009.

If Hollywood hasn’t optioned the story of Rags and Sarge, it should.

A Good Man is divided into three parts. The first consists of a series of Mark’s recollections of his father, broken down by theme (faith, hope, love, fatherhood), and the third recounts the events surrounding Sarge’s funeral, but, for my money, it is the second that is most powerful: In it Mark describes what happened when his father slipped gradually into Alzheimer’s grip. Managing his father’s decline was the hardest thing Mark had ever done; it required him to call on spiritual reserves he’d never tapped before. But inspired by the example of Sarge’s goodness and unconditional love and wisdom, which pierced through the fog of Alzheimer’s, Mark persevered.

Even as his mind deteriorated, Sargent Shriver’s faith sustained him.

“Dad,” Mark says to him, “you are losing your mind. You know that. How does that make your feel? How are you doing with that?”

Sarge’s reply: “I’m doing the best I can with what God has given me.”

In the aftermath of his father’s death, Mark was initially put off by how people kept telling him his father had been “a good man.” This was, he thought, the sort of banality that every bereaved child hears endlessly from consoling mourners. But he came to realize people meant it. Yes, his father had been a Great Man, striding across the stage of history; but he was also—in his humility, his genuine humane interest in every person he met, his ability to be at once a peer of the rich and powerful and best friend of his driver—an unusually good one.

When the audience roared at President Clinton’s eulogy, Mark felt relief and gratitude. Although “I had had a father whose shoes I could never fill, against whom I would never measure up yet,” he writes, finally, “I felt no pressure do so.”

In recounting his struggles to live up to his father’s legacy of greatness, Mark Shriver conveys the force of his father’s goodness. In so doing, he reveals his own goodness—which I suspect his father would have said was more important than mere greatness.