In New York’s scorching summer of 1940, Alan Scott toiled on the railway lines. His prospects were limited and his job, perilous. In mid-July, a tragic bridge collapse would have ended his story—were it not for the appearance of a magic space lamp. Alan Scott picked up the powerful lantern, and took its name for seven decades of green flaming and Justice League-ing.

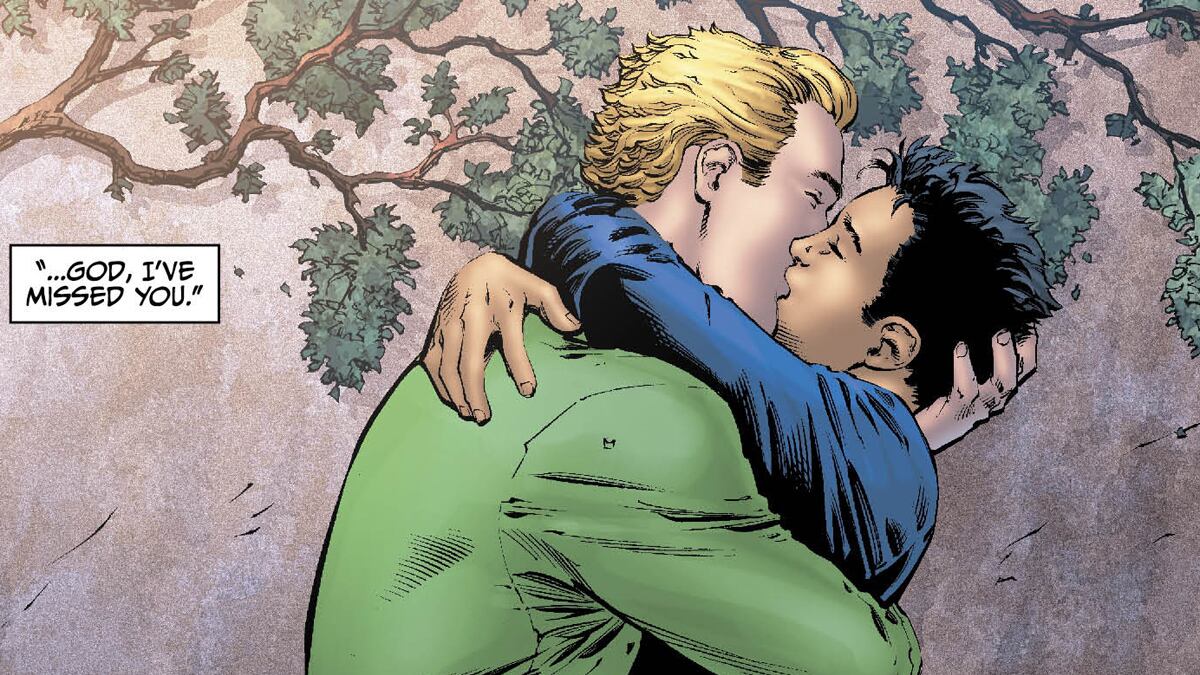

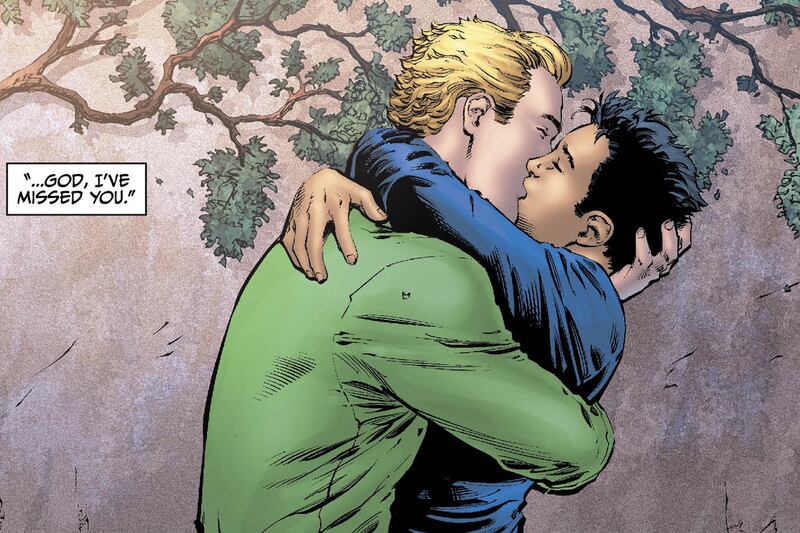

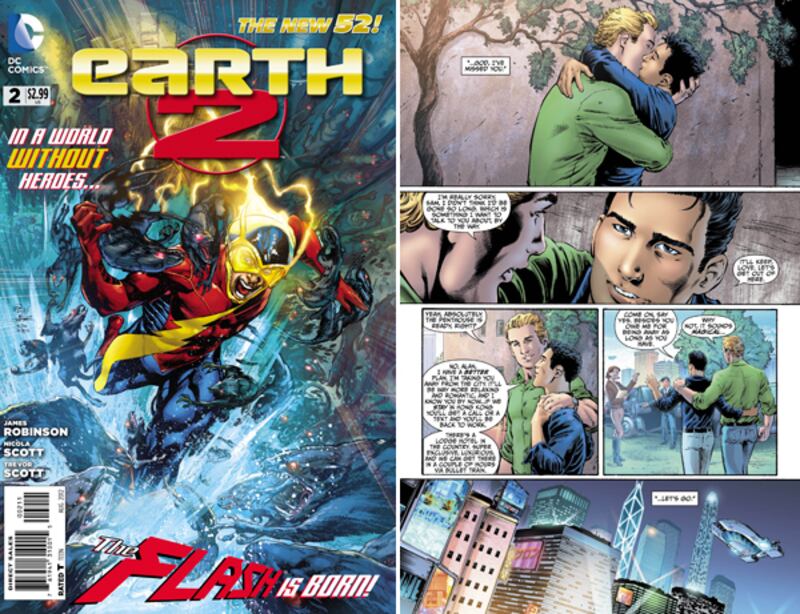

Last week, DC Comics announced that it will reintroduce Alan—the first of at least six Green Lanterns, depending on how you count—as an openly gay man. Normally, when an octogenarian comes out of the closet, it’s fodder for an endearing Christopher Plummer performance. But DC’s PR move is a window into a changing industry. It’s a decision that may have less to do with diversity than it does with new dynamics in the comic-book business, which has seen about as many booms, busts, “zooms,” and “thwacks” as its characters. Switching up sexual orientation is a cunning way of compensating for flagging sales and aging characters. In the meantime, the industry is rebalancing: toward independent publishers, author ownership, and cross-platform digital tie-ins. As small studios sap talent from the giant conglomerates, comics are changing—and there’s a lot of money to be made in the process—just not in the comics themselves.

The business world of comic books is a curious place. The “big two,” DC and Marvel, own the rights to pretty much all the superheroes you know, but most of the artists and writers who actually created them—and those who now draw them—have no intellectual property. Although most artists would love to start at DC or Marvel, the comics’ classic heroes just aren’t selling as well as they used to. In the meantime, investors and creators are seeing major opportunities at independent studios, like Image, Dark Horse, IDW, and Man of Action. In the past year, these groups’ successes have inched up comic sales for the first time in several years, bringing other titles with them.

The heroes of yesteryear—Batman, Superman, Iron Man—still have tremendous value. But today, their worth has almost nothing to do with their printed personae. All the power is in the merchandise or on the silver screen. Marvel is owned by Disney, and DC, by TimeWarner. To the parent corporations and their mega movie studios, the core comic business is practically a rounding error. According to Tony Wible of Janney Capital Markets—who has covered Marvel, DC, and their parent companies—the comics are “too small to move the needle.”

The numbers are stark. According to Comichron, which aggregates official sales data from Diamond Comic Distributors, the size of the entire North American comic market in 2011 was around $670 million; it's been that size since 2007. By contrast, The Dark Knight alone grossed more than a billion dollars at the box office. A core Marvel or DC character is worth practically nothing in the pages of the comic book that birthed him. “It’s not about comics, per se,” says Wible. “It’s about the storylines and characters. Disney gets to take these thousands of characters that Marvel has and find different ways of monetizing them.” A Marvel comic may be a place to “test” a potential movie storyline—but not to risk a merchandisable brand.

And so today, within the comic-book industry itself, many of the biggest, best-reviewed hits are indie: written by artists who self-publish and own their characters—guys like Robert Kirkman, cult hero and creator of the smash hit The Walking Dead. Paradoxically, nowadays you can make a lot more money outside the corporate mainstream. The big two still do good business and make big movies: billions in sales.

But Kirkman says “there’s a freedom that comes from not being at Marvel and DC.” There’s a lot of money, too. His Walking Dead is one of the few comics to ever breach The New York Times top 10 for all books. The TV tie-in is the highest-rated, basic-cable drama ever.

Steven Seagle, another indie publisher, helped shape Northstar—Marvel’s first openly gay superhero—in the mid-’90s. In fact, Northstar’s much-hyped recent marriage may have prompted DC to out the Green Lantern. Seagle liked doing the superhero thing: X-Men, etc. But he’s had a lot more success with his own studio, Man of Action, which retains merchandising benefits for Ben 10, a multibillion-dollar franchise, now on Cartoon Network. Had Kirkman or Seagle written their hits at DC or Marvel, they’d be worth a tiny fraction of what they are today.

Meanwhile, to attract new customers to old brands, the big two have adopted marketing strategies that can seem a bit gimmicky—having Archie meet Sarah Palin, or President Obama high-five Spider-Man. Creatively, they’re low risk. Alan Scott may be coming out as gay, but he’s only one of six possible Green Lanterns. If his storyline refresh doesn’t work, DC can always shuffle him offstage. As comic journalist Rich Johnston, who first broke the gay Green Lantern news, told me, “We’ve had black Superman, black Spiderman, lesbian Batwoman—but they’re never quite as popular as the original.” As Eric Stephenson, publisher of Image Comics, puts it, the big two are “trying to find an angle that says ‘we're still relevant.’”

If it really wanted to take a risk, DC could have outed Batman. Last month, star comic writer Grant Morrison told Playboy that the dark knight was clearly “very, very gay.” (A billionaire bon vivant who spends all his time with a nubile youth in tights? Please.) But a gay Batman would require DC permission, not to mention a conversation with Christian Bale. Seagle says Green Lantern was “the safer choice.”

At the smaller studios, a writer or marketer doesn’t have to play it safe. As Kirkman puts it, “There’s no one coming and saying, ‘You can’t do that with him. We gotta put this guy on a lunchbox.” While Marvel and DC exclusively license and merchandise their artists’ work, Image owns no intellectual property beyond its own logos.

Just last August, DC threw out almost all their old superhero storylines and started over at issue zero: a move they hoped would hook new readers and e-readers. Critics called the venture “a letdown” or “a mixed bag.” Marvel tried the same thing with an “Ultimate” reboot. As Image’s Stephenson puts it, “They’re locked into those characters and trying to make sure people buy those things.” The big movies also present creative challenges. As Wible puts it, “complex storylines”—plot arcs “spread out over many comics”—have to be distilled down to marketable basics. “The reality is, they’re making a movie; they have to attract a mainstream audience, from the 5-year-old to the 50-year-old. You tend to find a lot of compromise there.” Losing the Hulk’s nuances, you get bad movies. “It’s hard to feel sorry for someone who’s indestructible.”

Elsewhere “there’s a shift away from the same-old-same-old.” There’s a preponderance of talent, and gurus like Johnston and Kirkman say comic-book quality is high, even with the old-school brands. But sales aren’t keeping up. The year 2011 was a good one, but its best issues sold just over a hundred thousand copies. A decade ago, a hit could move millions. According to Comichron, which tracks sales data across the industry, sales have either declined or flatlined since 1997. Meanwhile, the collectors’ market has essentially collapsed. Given the huge success of comic tie-ins and geek chic—blockbuster movies, television shows, San Diego ComicCon, The Big Bang Theory—issue sales could and should be higher.

Are Marvel and DC to blame? Probably not—at least no more than dispiriting trends in print readership in general. Regardless, it’s clear that the old model isn’t sustainable: it isn’t tapping the pent-up demand for comics. According to Wible, “The big thing for Warner Brothers is not the comics.” And so, says Seagle, the “business strategy is changing tremendously.” Although the big two “have acquiesced” and are “doing just superhero universe stuff in the classic mold,” the smaller studios are gearing up for some creative destruction. “The market forces have pushed people out, since the profits coming from small or independent presses are bigger.”

The way to keep sales steady is to mine new nuggets out of old material. But the best way to boost them is with new content, new characters, and new platforms. DC is taking note, with a successful iPad Smallville tie-in. But as Kirkman puts it, “The sales at the larger companies are stagnating. We’ll soon see a tipping point where original, creator-owned ideas will have an equal share with old-guard ideas.”

More competition in the comic industry is a good thing for all parties, and Marvel and DC aren’t short on talent. But to bring back the sales of yesteryear, the publishers will have to do more than court PR with gay bombshells or current-events blitzes. And who says you can’t make an old hero new? In 1970, the Green Lantern and Green Arrow put their powers aside and loaded themselves into a run-down pickup truck. They wanted to journey cross-country and find “the real America.” In “Hard-Traveling Heroes,” the men drifted through tales of hippies, prostitutes, war protesters, and drug addicts (they even did some dope themselves). Surprise: the series was a megahit.