One evening last winter, over a Moscow dining table crammed with bottles and ashtrays, I sat and listened to a fellow dinner guest explaining how Stalin actually “only” killed 850,000 people, not 20 million. Most of the inmates of the Gulag were, he said, “genuine traitors.” This was no elderly crank speaking but Alexei Belayev-Guintovt, a fashionable 40-something painter and winner of the Russia’s most prestigious art award. His weirdly brilliant work features heroic depictions of Albert Speer–like visions of a neo-Soviet Moscow of the future, complete with shining red stars. Stalin was the last Russian leader who knew how to bring order, intoned Belayev, but American stooges like Gorbachev and Yeltsin had betrayed his great legacy.

So Stalin and the Gulag are kept alive today, in the imaginations and prejudices of a surprising number of modern Russians, in a way impossible to imagine contemporary Germans speaking of Hitler and Auschwitz. “Even victims of oppression take pride in the accomplishments of the Stalin era, paradoxical as that may seem,” says Orlando Figes in an interview. “In schools the emphasis is on the Stalin era as one of great achievement … Vladimir Putin tells Russians they shouldn’t beat themselves up about their history, that they shouldn’t feel bad about being Russian.” It’s timely and important, then, that Figes has written a new and powerful study of the Gulag, seen through the eyes of two of its prisoners.

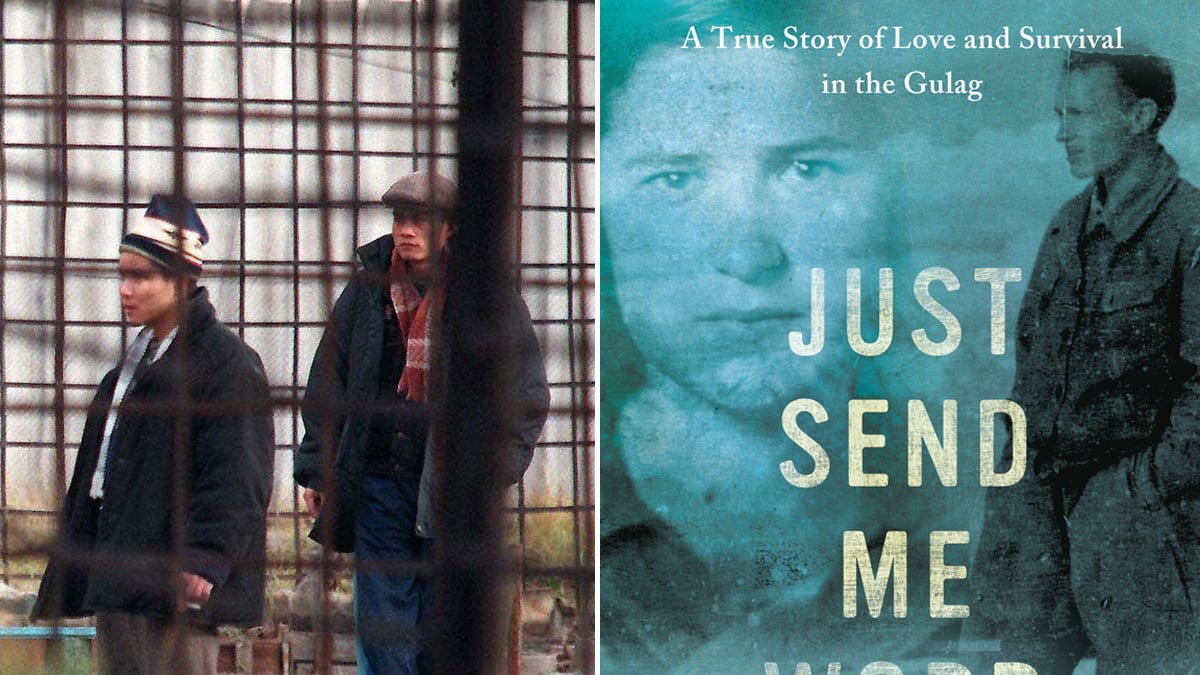

Just Send Me Word is an intimate view of one of Stalin’s most notorious labor camps based on a remarkable cache of letters smuggled in and out of the Gulag in the 1940s and 50s. Lev Mishchenko is a 29-year-old former Red Army soldier who had the misfortune to be captured by the Nazis—which makes him, in Soviet eyes, a traitor. He is liberated by the Russians from a German concentration camp, only to be sent to Stalin’s Arctic Gulag where millions of convicts toiled on railways, canals, and mines in murderous conditions. But in 1946 Lev is given a reason to survive in the form of a letter from Sveta, the sweetheart he had hardly dared hope was still alive. Over the next eight years the lovers managed to exchange more than 1,500 messages, and even to smuggle Sveta herself into the camp for secret meetings.

As Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the greatest chronicler of the Gulag, knew very well, the personal story is the most powerful literary vehicle of all. Solzhenitsyn’s three-volume “literary investigation” of Stalin’s terror, the Gulag Archipelago, is epic, comprehensive, and forbidding. But it’s his short work, the intensely personal One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, that really brought the horror and humanity of the Gulag alive to millions of readers. So it is with Just Send Me Word, a heroic love story amid the squalor and degradation of the Gulag. “How many times have I wanted to nestle in your arms but could only turn to the empty wall in front of me? I felt I couldn’t breathe. Yet time would pass, and I would pull myself together. We will get through this, Lev,” writes Sveta at the beginning of their long secret correspondence. Lev is electrified when he receives her letter. “As if it were alive, your handwriting! For three years I had managed to keep safe a tiny scrap of paper with your handwriting—it was all I had of you—until it was confiscated in the full search at Buchenwald. I lived with the hope that you were still alive and that I’d see you again.”

Lev, the son of a Moscow intelligentsia family, was luckier than the fictional Ivan Denisovich. Rather than felling wood he was put to work with a team of electrical engineers in one of the Gulag’s hundreds of laboratories. “I’m sitting in cultural and ‘scientific’ surroundings among jars, weights, flasks and test tubes and I’m writing to you in complete silence, pleasantly disturbed only by the sounds of a mazurka on the loudspeaker,” wrote Lev. Despite the risk and the remoteness of the Pechora camp, Sveta longed to get into the Gulag to visit her lover almost as much as Lev longed to get out of it. Wearing an Army uniform and traveling on a false ticket she made her way to Northern Siberia, where a friendly free worker who worked alongside Lev in the gulag’s Industrial Zone agreed to smuggle her in. The hurried meeting, and the terrible risk they had both run, left them both exhilarated and despairing. “Lev’s spirit had soared with Sveta’s visit,” writes Figes. “But her departure had left him sadder than before. It underlined what he had been missing for so long—what he would now have to live without.”

What gives Just Send Me Word its power is the intimate, granular detail of Gulag life, of how men and women attempted to create a semblance of normality in the most abnormal of circumstances. In other words, how people stayed human. They organized football teams, painted portraits with improvised paints, swapped the few books allowed to prisoners—even as men died around them and convicts returned, frostbitten and broken, from nearby “harsh regime” labor colonies. Later, after a rare bit of humanity from the Gulag authorities, Lev and Sveta were even able to see each other in an official “house of meetings,” an area of the camp set aside for conjugal visits.

But unlike House of Meetings, Martin Amis’s 2006 novel about the Gulag, Figes avoids getting tangled in the overarching moral implications of his protagonists’ plight. Amis made a brave attempt at getting his mind around the enormity of suffering inflicted by Stalin. But Amis ultimately failed because, as Boris Pasternak wrote after a trip to the famine-ravaged Ukraine, “there was such inhuman, unimaginable misery, such a terrible disaster, that it began to seem almost abstract, it would not fit within the bounds of consciousness.” Even the great chroniclers of the Gulag—Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Varlaam Shalamov, Yevgeniya Ginzburg—could only really describe the Gulag is it was lived, a day at a time. “The days rolled by in the camp—they were over before you could say knife,” says Solzhenitsyn’s Ivan Denisovich. “But the years, they never rolled by; they never moved by a second.”

Figes is blessed with extremely powerful material, in the form of a trove of Lev and Sveta’s letters handed in to the archives of Memorial, the Russian charity that chronicles abuses of power, historic and present-day. Their correspondence is the only known real-time record of life in Stalin’s Gulag, unmediated and uncensored. Wisely, Figes lets his characters speak for themselves. Their authentic voices are worth that. “When I wrote about victory, I meant our victory. Not victory over us but victory over everything cruel that we’ve had to face, over the burdens that have made us stumble and caused us pain,” writes Sveta. “I don’t want the pain to make you forget even for a moment all the good in the world—the earth and the sun and the water and, most importantly, people and relationships. I don’t want this joy to subside, and I want us to be young for a long time … if the world is lit up already, then I hope it stays as bright, despite the laws of physics and regardless of the distance from the source of light.”

The great irony is that all the best historiography on Stalin—beginning with Robert Conquest’s groundbreaking The Great Terror in 1968, through Simon Sebag Montefiore’s The Court of the Red Tsar and Anna Applebaum’s The Gulag to Figes’ own The Whisperers—has been in English, not in Russian. Figes’ own works on Russian cultural and social history, despite being international bestsellers, haven’t been able to find a publisher in Russia itself.

Partly, Figes admits, it is because “foreign intellectuals lecturing [Russians] on how bad their history is are resented.” Partly it has been because of criticism from Memorial and Russian academics about factual inaccuracies in The Whisperers, which Figes says he “regrets.” But partly because most Russians would prefer to see Stalin as the architect of victory over Nazism—Russia’s defining achievement of the twentieth century—rather than as the murderer of millions of his fellow citizens. If Russia is great, in the moral arithmetic of historical revisionism, Stalin has to be great too. More, “to question Stalin is to question what you did under Stalin,” says Figes.

Solzhenitsyn was the last Russian writer to confront that terrible question. “Where did this wolf-tribe appear from among our own people?” he wrote in The Gulag Archipelago. “Does it really stem from our own roots? Our own blood? It is ours.” Figes, in Just Send Me Word, brings us closer to an understanding of the horror Stalin’s victims went through, in their own words. Russian readers, though, don’t yet seem to be ready to face such knowledge themselves. Could it be, to paraphrase T.S. Eliot’s epoch-defining line, that after such knowledge there can be no forgiveness?