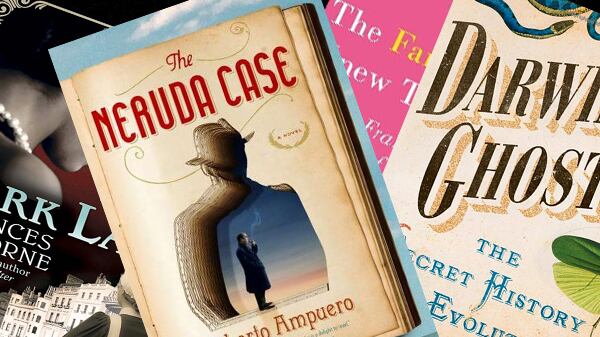

The Neruda Case by Roberto Ampuero

A real sense of fun permeates this mashup of a detective novel of international intrigue with the figure of the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.

In a time when zombies and sea monsters have visited upon Jane Austen and Abraham Lincoln has been tasked with hunting vampires, one wonders if there is any icon that the publishing world would not summon for a resurrection. A memoir by shape-shifting alien Aristotle? A muscular T.S. Eliot in a gay superhero comic? George Eliot, samurai warrior? How about this: Pablo Neruda gets the detective treatment, and a character straight out of film noir helps the poet navigate through some international intrigue involving Allende and the Stasi?

Ampuero is a noted Chilean author, but also the country’s new ambassador to Mexico, a guardian of diplomatic secrets. The hope is that the author didn’t draw too much of the fanciful Sherlock-Holmes-meets-le-Carré plot from life—it’s all too silly if foreign affairs actually work this way. There is a lightness of touch, a real sense of fun, as if the private eye, Cayetano Brulé, is on tip-toes. The title of detective was “bestowed by a shady distance-learning institute in Miami,” and everyone seems to think he can do his job simply by reading Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or Agatha Christie. A predecessor of sort is Umberto Eco, who’s been writing detective stories about Aristotle and the Knights Templar for decades, though Ampuero’s effort is far less didactic. A superb translation by Carolina de Robertis whips the first of Ampuero’s novels to be published in English into a pulsing, panting work.

Darwin’s Ghosts by Rebecca Stott

Everyone thinks evolution is a simple idea. Yet in this intellectual history of Darwin’s predecessors, what emerges is how much Darwin stands apart from them, because of natural selection.

Of course Darwin stood on the shoulders of giants and didn’t think of natural selection in a vacuum. But in 1859, Darwin received a letter from an Oxford geometry professor who accused the naturalist of “failing to acknowledge his predecessors.” Darwin responded by tacking on a list that included Aristotle (although Darwin hardly read him, and Stott says he was misled by a town clerk who persuaded him that Aristotle was a evolutionist), Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and Alfred Russel Wallace (who discovered natural selection independently of Darwin) to the American edition of On the Origin of Species. Stott takes this “historical sketch” as the excuse for a brisk overview of the history of evolution, outlining the contributions of the Arab writer Al-Jahiz, the French philosopher Diderot, and many others.

“How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!” the philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer famously responded to Darwin’s idea. It’s long entered the popular imagination that evolution is simple and hardly surprising. And yes, evolution can be easily imagined—most notably by Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus. Yet one must understand that it is the specific details and science of On the Origin of Species that continues to prove, time after time, the resilience and accuracy of Darwin. His priceless contribution is natural selection, the mechanism of evolution itself. Everybody thinks they understand evolution, but all attempts to answer the meaning of life are rather worthless before the formation of natural selection, to paraphrase and splice together thoughts from the French biologist Jacque Monod and the zoologist G.G. Simpson. Evolution needs no watchmaker, and Darwin got that right, while others before him did not—what’s more, Darwin showed us how evolution works. It will be wise to keep that in mind.

The Fan Who Knew Too Much by Anthony Heilbut

The passions that drive the cultural historian Anthony Heilbut become clear in this collection of essays by a rapacious fan of gospel music, Jewish immigrant culture, and German literature.

If Darwin’s Ghost traces the influences on natural selection, The Fan Who Knew Too Much charts the influences on, well, Anthony Heilbut. In fact, “influence” is everywhere in the book, and the thread that connects these searching, web-like essays. “Aretha: How She Got Over,” surveys the many predecessors of the gospel diva—everyone from Billy Strayhorn to Billie Holiday, from Sister Rosetta Tharpe to Mahalia Jackson. In the best of the bunch, “The Children and Their Secret Closet,” Heilbut documents the gay community within the Pentecostal Church. In “Somebody Else’s Paradise,” he notes the obvious achievements of Germans who fled Hitler, too many to name. His favorite writers Joseph Roth and Thomas Mann round out his life’s passions, and The Fan Who Knew Too Much feels like a late Beethoven string quartet, drawing on a rich career’s obsessions and paying tribute to sources of inspiration.

Park Lane by Frances Osborne

After a delicious biography of her devil-may-care ancestor, Idina Sackville, Osborne tells the story of upheaval in the London aristocracy after World War I.

Park Lane is a breezy summer read for those fans of Downton Abbey who are craving their dose of upstairs-downstairs drama mixed with a surprisingly serious history lesson. Osborne’s previous biography of her ancestor Idina Sackville, The Bolter, took the English aristocracy’s bad behavior all the way to Kenya, but this novel stays home. It is 1914 London. Grace Campbell, 18 years old, takes a job as a housemaid at Number 35, Park Lane. (Daisy, is that you?) The daughter of the house’s master joins a suffragette group. (Hi, Lady Sybil!) In this potpourri of radical politics meets debutantes, Frances Osborne tells the story of the tough and even violent fight by women, often aristocrats, to gain the vote. Against the backdrop of perfect cups of tea and impeccable manners, it’s about as radical as the British have ever gotten. Paging Julian Fellowes to adapt.

The Choke Artist by David Yoo

A writer with a talent for self-deprecating humor remembers his childhood working to become the only ‘underachieving Asian-American teenager.’

Yoo’s first foray into nonfiction possesses the same cringe-inducing, self-deprecating humor evident in his novels. The Choke Artist is a memoir, and Yoo chronicles his life through a series of humiliating events beginning when he was a 16-year-old high school junior and leading into his adulthood. Whether fleeing the scene of the nursery playground after a botched high school hook-up, or pretending to be Japanese in order to impress his boss (Yoo is actually Korean-American), this guy just can’t catch a break.

By his own admission, Yoo was a kid working to become the only “underachieving Asian-American teenager” in a society that applauds stand-outs; he’s more determined to disprove the stereotypes by using a yellow highlighter to draw on his arm during class than to study. The book’s humor belies a deeper story: that of an insecure child, conscious of his status as the only minority growing up in an all-white, upper middle-class suburb, torn between his desire to cultivate his own identity and his fear of being different.

—Luke Kerr-Dineen