The Etan Patz case might have been made if the detectives searching the prime suspect’s home had found the junior flight captain hat the 6-year-old had on when he vanished back in 1979. Just as persuasive would have been the light blue sneakers with the green lightning bolts on the side or the blue satchel decorated with white elephants. But the child-size clothing the detectives found during a June 6 search of Pedro Hernandez’s Maple Shade, N.J., family home did not match anything Etan was known to have been wearing.

Nor was there reason to believe that the Matchbox car they found in Hernandez’s home had any connection to the missing boy.

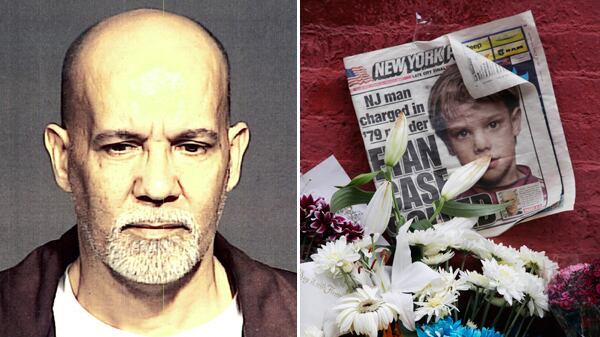

So, three weeks after his arrest, the case still rests on the largely uncorroborated confessions that Hernandez allegedly made first to relatives in New Jersey years ago and then to police last month. His wife and his extended family have questioned the validity of those statements, saying Hernandez suffers from delusions. His lawyer says Hernandez is bipolar and schizophrenic, an assertion that is presently being weighed during an extended psychiatric evaluation in the prison ward in Bellevue Hospital.

According to a forensic psychiatrist who once worked at the hospital, protocol calls for Hernandez to be interviewed by staff psychiatrists and kept under continual, detailed observation, including how he interacts with others during group therapy and in the dining hall. “Somebody will be looking at him most the time if not all the time,” the former Bellevue psychiatrist says.

During interviews, doctors are seeking to determine the presence and nature of any mental illness, as well as any indications that Hernandez is faking. They may ask a question such as, “When you hear voices, is it louder in the right ear or the left?” An actual schizophrenic should answer “neither.”

At the same time, psychologists almost certainly are administering a battery of standard tests, including Rorschach and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. These most likely will be used only to confirm what the psychiatrists determine on the basis of the firsthand clinical observation, along with whatever medical records might be available.

Few of those who believe Hernandez is guilty will be surprised by a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. “Which is basically what a lot of murderers have,” the psychiatrist says.

But a person can show all the symptoms of that disorder and suffer other illnesses as well. “You can have no conscience and feel you’re exempt from the normal rules of society and you can also be schizophrenic,” the psychiatrist says.

By the time Hernandez is next due in court, on June 25, there should be an official appraisal of his current mental health. His condition at the time of Patz’s 1979 disappearance will remain a matter of conjecture. Hernandez was 18 then, and schizophrenia often begins to present itself in the late teens and early 20s. But it is also often a progressive disease, growing more profound, not less, over the years. “And like diabetes, it can be mild or severe,” the psychiatrist notes.

Hernandez’s overall psychiatric profile no doubt will have an impact on how credible a jury may find his alleged confession, should he go on trial.

In the meantime, police are still looking for corroborating evidence.

Detectives say they may have found a possible motive when Hernandez told them during the alleged confession that a photo of Patz reminded him of a nephew he despised. An older relative told the police that Hernandez spoke of seeing “the devil” in the boy, who was 3 at the time Patz vanished.

The nephew, Sammy Santana, is now 36 and has grown up to become a New York City sanitation worker. That has its ironies: Hernandez allegedly told police that after strangling Patz in the basement of the bodega at which he was employed, he placed the body in a bag and then a box that he set beside some trash cans around the corner. The police had hoped to trace where the body would have been taken, but the Department of Sanitation apparently has no records dating back to 1979.

New York detectives may be seeking to interview the three sanitation workers assigned to Manhattan West 2 who had that route at the time. A retired sanitation worker who had an adjoining route says the street where Hernandez allegedly placed the body probably had pickups five days a week, most likely after the street sweeper went through, sometime after 9 a.m. Patz weighed some 50 pounds, and the retired worker suggests that this would not have given one of his comrades pause.

“Just throw it in the truck with no problem,” the retired worker says.

That means Patz’s body could very well have been on its way to a barge on the Hudson River hours before he was reported missing and hours before the area was searched by some 300 cops. “Search of buildings, rooftops, basements and elevator shifts, backyards and alleys was conducted,” NYPD Sgt. Bill Butler wrote in his first report. “This met with negative results.”

Bloodhounds were brought in the next day, and it seemed a light overnight rain was to blame, as they went only as far as the bodega before doubling back. Butler continued to walk Patz’s last known route every morning for months. An NBC crew went with him one day and followed him into the bodega, where he spoke to the man behind the counter, apparently Hernandez’s uncle, Juan Santana.

“Hi, Juan,” Butler says in the video, clearly having spoken to the man before.

“Hi,” the man says.

“Hear anything? Anybody talking?” Butler asks.

“Not a word,” he says.

The man shakes his head.

“Saying anything?” Butler continues.

“Nothing at all,” the man says.

“OK, thanks a lot,” Butler says.

“Keep your ears open,” Butler says.

“OK,” the man says.

Butler’s soulful and earnest dedication makes the encounter all the more eerie. It also adds to the tragedy of his subsequent suicide for reasons that were apparently not directly related to the case.

Hernandez was arrested last month after a family member called police. Detectives found Hernandez’s alleged confession under questioning credible, partly after he told them he had lured Patz down into the bodega basement with the promise of a soda. Julie Patz had told police early on that her son left that fateful morning with a dollar in his hand, saying he planned to buy a soda before he got on the school bus. The bodega was the only place on his route to the bus stop where he could have possibly bought a soda.

In her book on the case, After Etan, Lisa Cohen recounts how a neighbor named Karen Altman stopped by the Patz loft when it was a kind of command center, crowded with cops and others anxious to help. Altman asked if there was anything she could do.

“Yes, go down to the bodega and get everyone a soda,” Julie Patz said.