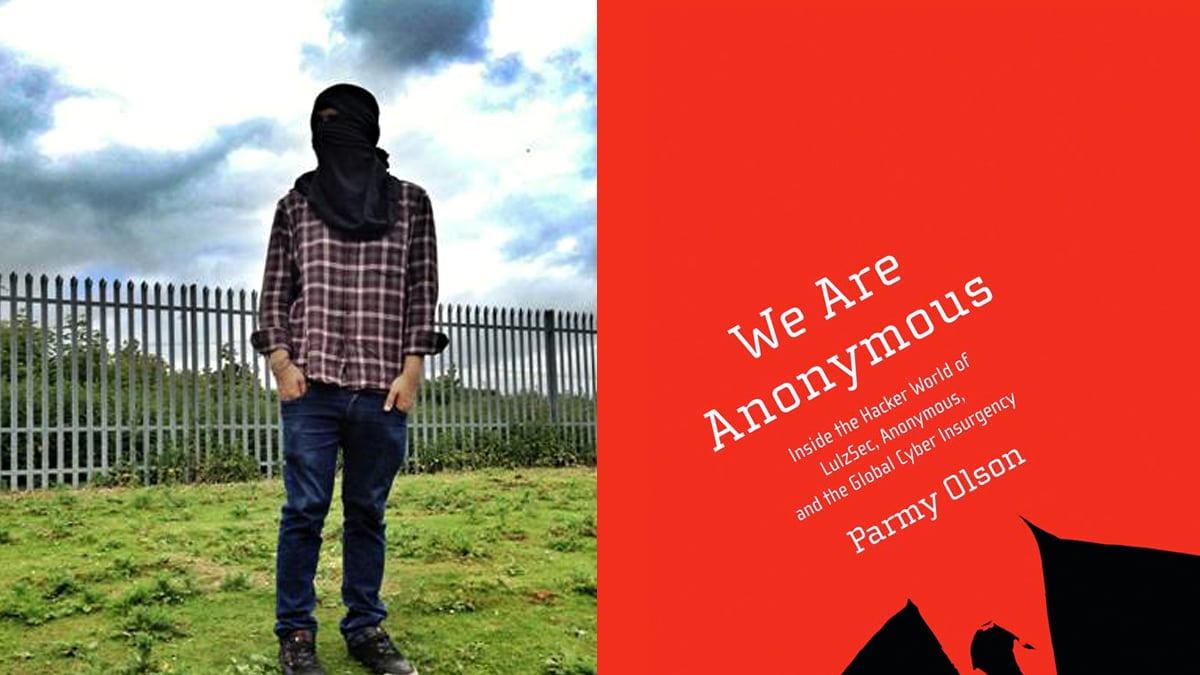

The sound of a milk steamer roars in the background in a coffee shop, where William is sitting at a table and drinking idly from a cup. He is a young man, early 20s, dressed in a checkered red shirt and low-slung jeans, who wouldn’t look out of place wandering around his local shopping mall or riffing with friends over a beer. William has a few secrets, though, and one of his biggest is that he aligns himself with Anonymous. This is the online community of hacktivists and Internet trolls that’s been running riot across the Web for the past few years.

William (not his real name) is somewhat hardcore. He insists that he is part of the original Anonymous—like a Roman Catholic who sees himself as being part of the “one true church.” He says this part of Anonymous started it all, laying the foundations for the current nebulous community and injecting it with all the necessary elements of subculture: the memes and the lingo, the profound social acceptance and the disdain for authority, the intent to harass people for fun or “lulz.” Things that made it attractive and fun.

The “hacktivist” Anons who attacked Stratfor last year, and PayPal and MasterCard the year before, the ones who wear the Guy Fawkes masks and protest against acronyms like CISPA and ACTA: they’re a “joke,” William grumbles. A pair of elderly ladies at the table next door look in his direction over their cups of tea, and he lowers his voice a little. The real, true Anonymous lives on 4chan, William says, a website visited by millions of people each month. So-called trolls who are the Joker to the hacktivists’ Batman. Young men who, like William, are happy to watch the world burn. In essence, it’s his home.

William first found 4chan when he was in his early teens, around the same time he and his friends were “pedo-bating” on MSN chat and other websites. They would come online with a nickname like “sexy_baby_girl” and pretend to be an underage teen who wanted to see an older man masturbate on a Web cam. Once a man showed up on video, they’d suddenly type out a fake IP address, say it was his and that they were from child protection services. As the men suddenly fumbled for the mouse to turn it off, they’d fall about laughing. William always wanted to take the joke further, to get the man more excited. When it was over, he’d go home and carry out the pranks on his own.

Over the years he turned this into a skill to troll people in some of the most mortifying ways possible—manipulating men and women into sending naked pictures of themselves or their genitalia, then blackmailing them or embarrassing them with the images. Once, for instance, he hacked into a young man’s Facebook account and posted pictures of the man’s penis on the wall of a family member. “Hi mom, here’s my cock. What do you think? LOL,” went the caption.

William suffers from depression, as well as reoccurring thoughts of suicide, but he claims that time spent on 4chan helps him get through it all. He’s seen so much porn, gore, and abuse online that he’s numb to it. It doesn’t bother him. “It wastes a night,” he says. Instead, on 4chan and through Anonymous, he finds both a reason to keep going and profound social acceptance. The kind you can’t find anywhere else in the real world.

Many people who end up joining Anonymous (and anyone can—there is no initiation rite or rules around membership other than that you try and stay anonymous) often say that they found it through 4chan. The website is said to be the home of Anon, after its creator, Christopher “moot” Poole, forced users to join in the rapid fire discussions without nicknames—always as “Anonymous.” When the site’s core users started spamming rival sites, or MySpace pages with gore and porn en masse, Anonymous as a collective, dynamic entity was born.

“People claim not to remember how they found 4chan,” William says. “But usually it’s because they were looking for nasty things online.” The beauty of the world they inhabited was people’s complete, unfettered honesty about their weirdest habits and sexual proclivities. You didn’t have to pretend here. The other night, for instance, someone was asking around for “rule 34,” which is 4chan lingo for porn (a derivation from the “47 Rules of the Internet”) of a female character from TV’s Glee with Down syndrome. Users responded in kind, by posting Photoshopped pictures of the girl.

“There are parts of me I can’t share with people in real life - parts they won’t accept.” But in Anonymous—and for William that means 4chan—he could talk about them freely. This, naturally, made for some warped morals. But it also meant that behind all the headline-grabbing exploits of Anonymous, from hacking MilitarySingles.com to paralyzing the website of PayPal, was a secret understanding about people’s biggest vulnerabilities and social inadequacies.

It takes cunning to predict how the horde would move, William notes. Post a request on /b/ to destroy an ex-girlfriend and scores of users will respond with NYPA, or “not your personal army,” then try to attack the original poster (OP). So you manipulate, and disguise the real request behind layers; call on users to attack the ex, to help a friend, and post a link to both people’s Facebook profiles. The horde will inevitably turn on the friend, cracking his account and spamming his Facebook wall with porn and gore, when all the while he was the original target.

Recently the issue of “SWATing” has been in the news, after some Internet hoaxers made 911 calls that resulted in SWAT teams swooping on the homes of at least two conservative bloggers. That’s nothing new for William, who’s seen SWATing discussed on 4chan for years. “Perfect trolling,” he says. “SWATing keeps things fresh. It’s also spiteful and malicious in the way that I personally think Anon should be. As for the political side of it, I couldn’t care less.”

William is one of thousands of core and casual adherents of Anonymous, which vaguely lives on either 4chan (22 million unique visitors a month) or on Internet Relay Chat networks like VoxAnon IRC and AnonOps IRC. Some IRC channels see hundreds of users each day, and tend to house those with more activist intentions, those who believe Anonymous should use the Internet as a battlefield, not a playground.

One technically skilled hacker who frequents these IRC networks agrees with William, however. He has been part of Anonymous since January 2007, thanks to visits to 4chan, and says Anonymous has lost its way.

“At first we would try to cause chaos, lulz, whatever to have fun,” he says. “We would call them raids.” This hacker has taken part in some of the earliest, headline-grabbing stunts by Anonymous, helping for instance to take down the website of radio talk show host Hal Turner in early 2007. In the past few years he’s moved away from Anonymous, helping out with hacks where he can but with far less enthusiasm, especially when things are done for a socio-political cause. “A lot of times I help people exploit stuff, give advice and what not,” he says, but he’s wary of the growth of attention from the media and the FBI.

Many supporters of Anonymous disagree that the extra attention is bad. They contend that Anonymous is now a platform that gives individuals a voice and causes a stir. Their “brand” fully exploits the way the Internet can be used to manipulate perceptions, one of its most successful feats being to project a mirage of scale and power. When Anonymous hit PayPal and MasterCard in December 2010, for instance, most of the firepower came from a few supporters with botnets, not the thousands of volunteers who’d downloaded a so-called DDoSing tool. But the media and even some authorities believed it the work of a teeming horde.

In fact, some of the most dramatic attacks carried out by Anonymous in early 2011—attacks on the websites of repressive Middle East regimes, the “live hack” of the Westboro Baptist Church, the devastating theft of thousands of emails from HBGary Federal—were carried out by a small team of particularly enthusiastic individuals in the U.S. and Britain, who had nicknames like Sabu, Topiary, Kayla, and Tflow. With their early attacks, they credited the larger hive of Anonymous, sending shivers down the spines of authorities and corporations.

The group enjoyed working together so much on their early attacks that they reunited, Blues Brothers style, to create a splinter group from Anonymous called LulzSec. Feeling enlivened, and partly obligated to the fraternity they created, they went on to steal and publish customer data from Sony Pictures, hacked into PBS, and take down home pages of the CIA and an FBI affiliate called Infragard. Members of the group felt profound trust for one another, and were so wrapped up in the hype they’d created—after 50 days they had more than a quarter of a million Twitter followers and stories about them in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal—they were blinded to the consequences of their actions.

Their leader, a New York man with two daughters in his late 20s nicknamed Sabu, became an informant for the FBI halfway through their spree. Real name Hector Monsegur, he helped the FBI level charges on U.K.-based team members Topiary and Kayla. For his cooperation, Monsegur would get a lesser sentence. It was thanks in part to hubris and ego that LulzSec eventually imploded. Four people in the U.K. were arrested and they are due to plead in court later this month.

LulzSec, for a while, seemed to be the crowning achievement for those with Anonymous who thought its true role was to stick it to the man. This was only part of the true story—it was also a platform for a handful of people who felt isolated in real life, to find profound fulfillment and purpose in the cyberworld. If the Internet was a place where you could live out an alter ego, Anonymous and various nodes like LulzSec amplified that ability with purpose and moral justification; a digital, decentralized resistance movement that had many positive qualities, but which could also act as antidote for anyone who was drifting and impressionable.

And so comes the odd question of which camp should win out—the Jokers or the Batmen?—since the Anonymous phenomenon won’t go away any time soon. A more serious-minded direction seems right at first, but then that old, inflated sense of purpose can also lead to bigger damage. Witness the latest YouTube video released by Anonymous hackers, in which they claimed to have stolen three terabytes’ worth of data from government agencies. One of the hackers responsible later said in an interview that the theft was done in “revenge” for the FBI’s recent arrests of Anonymous supporters. The feds, they insist, are the bad guys.

This could be a dangerous viewpoint to cling to. Ask any observer of religious fanaticism and they’ll point to how a sense of moral righteousness can send groups’ abilities to make rational decisions spinning out of control. It’s easy to forget about consequences and structure when you’re causing damage for a higher cause.

Which brings us back to William and his strange world, the one of cold-hearted harassment toward innocents on Facebook, shared videos of gore and torture; general lawlessness. To his credit, he and others in the Joker camp seem to maintain a healthy, sobering skepticism about how much Anonymous has manufactured its own importance.

“Some men just want to watch the world burn,” William says, invoking Alfred’s quote from Batman movie The Dark Knight, now a popular online catchphrase. The other, morally minded supporters in the Anonymous movement, what William and many others dub “moralfags” should be more accepting of the world around then, William says. “But then …” he adds, “I guess I should be more accepting of them.” He is exasperated.

The other longtime Anon hacker is wary of Anonymous’s embracing everyone and anyone. “It was a lot smaller and more structured [in the past]. You had to be accepted,” he says. “Now anyone can join Anonymous.” As for the attempts at protest and sociological change, he is as skeptical as William, though perhaps because he simply misses the mean-spirited fun of the past. “I don’t think [Anonymous] can change much in the world,” he says.

“Before people thought we were a spiteful, Internet hate machine. Before you could revel in being a real prick,” says William. “Now people think we’re vigilantes and care about stuff.” Even 4chan itself has become more mild. The indecent images and links to videos are still there, but with less porn and gore overall and even an increase in competitions to make users smile. “It’s just a game,” William says, between munches of ready-salted crisps. He offers the packet, with at least half the snack still inside. “Go on, you can have the rest,” he says, all traces of the malicious Internet troll suddenly gone for a while.

Such is the case with the Internet and Anonymous itself, that things are never what they seem. Dastardly as William might appear in his online trolling, even that could start to look tame as the vigilante, Batman-style Anonymous continues to carry out bigger attacks that grab more attention and create more martyrs in handcuffs.