In 2002, John Podesta, former chief of staff for Bill Clinton, read a cover story in The New York Times Magazine about George W. Bush’s deputy secretary of defense, Paul Wolfowitz. The article, which was written by Bill Keller, praised Wolfowitz’s belief in democracy and “almost missionary sense of America’s role.” Podesta was startled. “You know, this guy actually has a coherent worldview,” he told his wife. “Unlike some of the other guys in the Bush administration, it’s not just political for him.” Then he joked, “Of course, if this guy’s worldview was right, the British would still be running India.” Podesta decided to search for a Democratic version of Wolfowitz, establishing two organizations, the liberal Center for American Progress and the slightly more hawkish Center for a New American Security. Each was supposed to provide a counterpart to the sprawling conservative network that has served as the movement’s powerbase in Washington, D.C. It didn’t turn out to be that difficult. After the Bush administration invaded Iraq and liberals such as Keller eventually concluded that the war was a “monumental blunder,” Podesta and the Democrats succeeded better than he and they could ever have anticipated, at least when it comes to foreign affairs.

Less than a decade later the tables are turned. Now it is the GOP that is flailing as it tries to depict Obama as a wussbag, while Democrats preen themselves on their newfound realism and toughness when it comes to taking out the world’s bad guys. Obama can claim the scalps of both Osama bin Laden and Muammar Gadaffi. While Mitt Romney implausibly declares that Russia is America’s No. 1 threat or huffs and puffs about bringing China before the World Trade Organization for currency manipulation, President Obama has moved decisively to disentangle America from Iraq and Afghanistan. Obama has also upped the drone war against al Qaeda and tightened sanctions on Iran. Obama may not be an imperialist, but he has fortified the imperial presidency as George W. Bush created it.

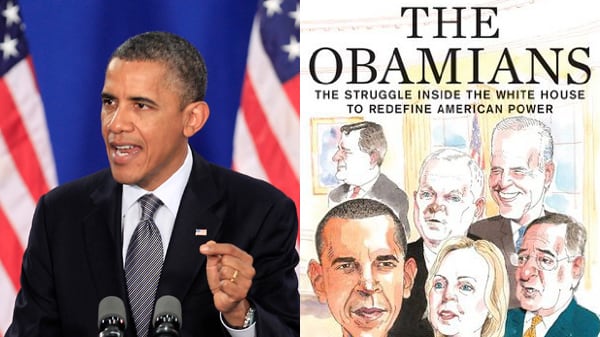

In The Obamians, James Mann seeks to explicate Mr. Obama’s planet. His new book is the successor to his bestselling Rise of the Vulcans, which explored the rise of Bush administration foreign-policy officials such as Condoleezza Rice, Paul Wolfowitz, and Dick Cheney. In it, Mann amply demonstrated his superior reporting skills, conducting interviews with numerous high-level officials to weave a compelling narrative. His new book follows a similar format. Mann offers compelling portraits of officials like Hillary Clinton, the late Richard Holbrooke, Samantha Power, and Obama speechwriter Ben Rhodes. Despite Obama’s adamant denials that he is overseeing a declining America—which have included touting Romney adviser Robert Kagan’s new book The World America Made—Mann suggests that the aim of the younger cohort, and, above all, the president, is to adopt a more modest definition of America’s role in the world.

At the same time, Mann suggests that Republicans and Democrats alike should not be entirely surprised by Obama’s willingness to use force abroad. He traces what might be termed the roots of Obama’s ferocity to his longstanding refusal to decry war itself as a bad thing. Obama’s ferocity can be selective—intervention in Libya, not Syria—but has, more often than not, manifested itself when American interests are directly threatened as opposed to a more general war for democracy. Mann emphasizes that Obama said the Iraq War was a dumb one and that he would up the battle in Afghanistan and pursue Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, which is exactly what he did. Whether the Obamians actually have what amounts to a doctrine—whether there is even such a thing as an “Obamian”—or are simply adapting to new realities, however, is the question that hovers over his new book. Will such a doctrine emerge as Obama searches for a legacy in his second term? Or will he be hostage to events in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia?

Mann begins his book with an excursus into the history of Democratic foreign policy after the Vietnam War, which is to say that he explores the battles that erupted among Democrats themselves over the use of force. The neoconservatives jumped ship during the Carter administration, convinced, as Jeane Kirkpatrick put it, that it had lost both Iran and Nicaragua as a result of pushing precipitously for change in authoritarian societies, for engaging in a kind of liberal social engineering—“A great weakness of liberal Democrats,” Kirkpatrick wrote, “is that they don’t learn enough about the societies in which they operate before they set about dismantling what is, and trying to encourage people to do something very different.” Of course this was the same charge that Democrats would end up lodging at the Bush administration and, it should be said, that Kirkpatrick herself viewed the second Iraq War with deep misgivings.

The debates in the Democratic party revolved around Vietnam and the use of force. Not until the Clinton administration did deploying the military really become acceptable among many Democrats, a number of whom enthusiastically championed entry into the Balkans Wars. Here is where what might be called the Holbrooke wing of the Democratic party emerged in full flower. Holbrooke’s protégés such as Samantha Power lacerated the Clinton administration for moving too slowly to stop Slobodan Milosevic and his allies from committing genocide. The term “to whack,” Mann notes, came into vogue among American foreign-policy experts—“it was used to connote a quick, almost causal application of American military power, aimed at bringing a recalcitrant country or its leader back into line—a demonstration of force, as if from a parent to an unruly child.” This is not the course that Obama has followed. Mann astutely observes, “Obama sought to carve out a less assertive role for the United States, one in which it occasionally demonstrated its continuing power and sought to preserve a leadership role in the world, but relied far more on the support of other countries.”

Of course this does have a back-to-the-future aspect to it. It was Richard Nixon who announced what has come to be known as the Nixon doctrine in Guam in 1969. He made it clear that there would be no more Vietnams and that America’s allies would have to pitch in first to take care of their security. Nixon believed that “polycentrism” had emerged and that other nations should “assume greater responsibilities, for their sake as well as ours.” More easily said than done, but Obama does not appear to differ substantially in his approach.

Or does he? Libya was a war of choice, one which Obama justified as a preventing a potential mass slaughter in the city of Benghazi. Obama was now listening to the Samantha Power wing of the Democratic Party rather than realists such as Brent Scowcroft, who counseled against intervention. Indeed, as Mann notes, “the intervention in Libya marked a turning point for Obama and his team. With it, the president took a step away from the foreign policy realism that had characterized his first eighteen months in the White House.” But Mann believes there is an even more serious criticism that can be made of Obama.

Throughout his campaign, Obama had proclaimed that he would not follow in George W. Bush’s footsteps in foreign affairs. But he has proved to be no less an imperial president than his predecessor. Specifically, “he was sending American forces,” Mann says, “into military conflict without going to Congress under the provisions of the War Powers Resolution. In doing so, he arguably asserted presidential power in warmaking beyond even the claims of George W. Bush.”

Such are the vicissitudes of foreign affairs. Obama, like not a few presidents, has found himself saying and doing things that are at violence with his statements as a candidate, a source of perplexity, vexation, and even fury to many of his supporters, some of whom have become erstwhile ones. Meanwhile, the champions of democracy promotion abroad have despaired about what they see as his gelid realism when it comes to Syria, where, as Ryan Lizza, speculates in the latest New Yorker, he may soon have to decide whether or not to employ American military might. Obama has opened himself up to the charge of hypocrisy. For the most part, however, he gives every sign of trying to muddle along. To expect him to control events would be to endow him with a power that no president has possessed. Even Ronald Reagan, credited on the right with singlehandedly bringing down the Soviet Union, saw it occur only two years after he had left office.

But are clarity of purpose and a clear strategic vision always desirable in conducting American foreign policy? A good case could be made that, more often than not, they constitute the road to disaster. Consider Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was a crusader whose aims could not have been clearer or more noisily enunciated. He wanted to make the world “safe for democracy.” But in endorsing the Treaty of Versailles and supporting the League of Nations, he ended up creating the very conditions that led to the rise of Hitler and World War II. Then there is Wilson’s unlikely legatee, George W. Bush. Like Wilson, who had entered office pledging to keep American out of World War I, Bush initially proclaimed that he would follow a humble path, as though he were some kind of mendicant taking a vow of poverty when it came to national egotism abroad. No sooner had the 9/11 attacks occurred, however, than Bush suddenly became a proponent of wars of liberation in the Middle East. The results were catastrophic.

It was not until his second term that George W. Bush abandoned the neocon elixirs that he had been imbibing and reoriented foreign policy toward a more cautious and prudent course that accepted the limitations of American power. Obama may represent continuity with Bush, as some of his critics on the left allege, but it is with the more realistic approach of the Bush who was sobered by the 2006 midterm election and received what he called a “thumping.” Obama’s neo-Bushian approach has transformed him into something he could hardly have imagined when he first ran for office. He has become a foreign-policy president.