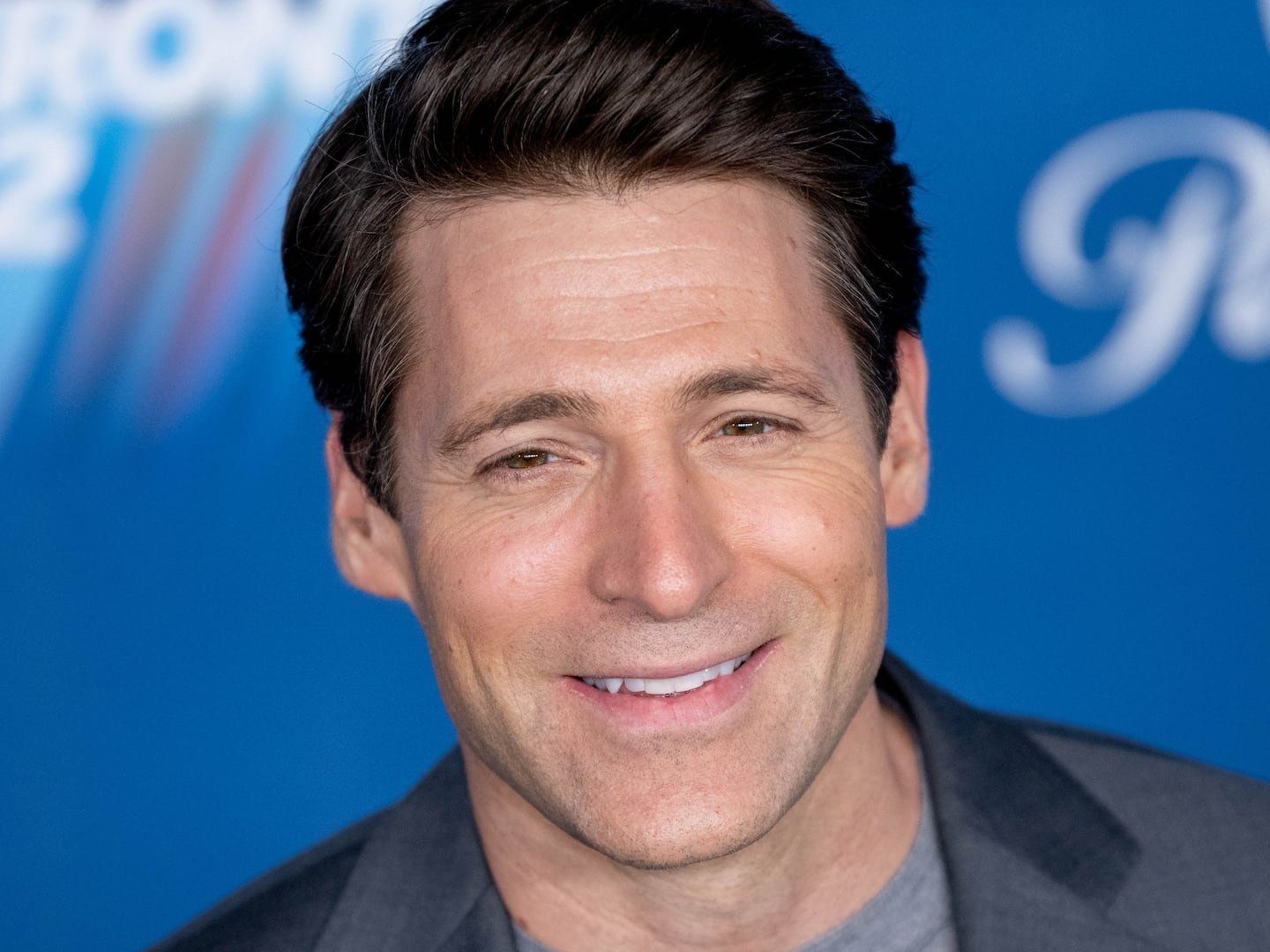

In Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy, Chris Hayes, Washington editor of The Nation and the host of MSNBC’s Up w/ Chris Hayes, tells a sweeping story of American decline that manages to tie together everything from the Tea Party to Occupy Wall Street to Major League Baseball and Enron.

The last 10 years or so, argues Hayes, have been a “fail decade”—a series of unmitigated disasters, from the economic collapse to the Iraq War. These events have been watched by an increasingly restive, impatient—and, in many cases, irrational—public. Why have things gone so badly? Hayes’ basic argument is that our elites, forged in a meritocratic system of intense competition (and self-satisfaction) have failed us, and their failures have seeped down through our most important systems and institutions, poisoning our economy, our politics, and the public trust.

The reason there’s such rampant discontent and paranoia right now, argues Hayes, and such a sense that America has become derailed, is because of the gaping and widening divide—social, legal, economic—between those who have access to society’s ripest fruits and those who do not. In an interview with The Daily Beast, Hayes quickly turned to an early example from this book—Hunter College High School, the ultra-competitive Upper East Side high school he attended. The only way to get into Hunter is to pass a rigorous entrance exam. So, on paper, it’s a truly meritocratic institution. “It doesn’t allow for game-rigging,” said Hayes. “If the mayor’s daughter doesn’t pass the test, she can’t get in.”

It sounds like a perfectly fair system, but over time, “that basic format of equal opportunity has been insufficient to protect the school from the rising inequality outside its walls.” Now, after decades of economic stagnation for those in the middle and at the bottom of the income distribution, Hunter has far fewer blacks and Latinos and far more whites and Asians, proportionally, than it used to, leading to a student body that does not represent New York’s very diverse population. As society has stratified, as it has become easier for rich parents to get their kids into test-prep boot camps (an industry that exploded as competition for admission to elite schools ramped up), the meritocratic ideal has been subverted.

Most Americans don’t realize just how bad things have gotten, just how quickly the top 1 percent and 0.1 percent and 0.01 percent have raced ahead of everyone else. When it comes to social mobility, Americans’ optimism far outpaces the facts on the ground, which are that the U.S. lags far behind comparable countries on this crucial measure. So instead of a concerted effort to attack inequality at its root, the result instead is surfeit of mistrust and lashing out on the part of the public. “Since people cannot bring themselves to disbelieve in the central premise of the American dream,” Hayes writes, “they focus their ire and skepticism instead on the broken institutions it has formed.”

“There’s this amazing tension between people’s beliefs about American life and the facts,” said Hayes. That’s why Americans are so quick to buy into the meritocratic ideal—it tells a much tidier, more just story, that in the end people get what they deserve. But this is pernicious, Hayes argues, because it blinds us to the eventual results of these sorts of systems. “It makes us complacent about inequality of outcomes,” he said. “We tell ourselves that as long as we can get the equality of opportunity right, everything will be fine.” But in a system where elites have more power than ever to protect their elite status, that simply isn’t how things shake out.

On the inside of elite institutions, argues Hayes, their members weave elaborate yarns about how they, the select few, got where they got simply by gumption and hard work. As he points out, even the most privileged of elites hold these stories near and dear; nobody wants to be perceived as having had their success handed to them, so “You see people constructing these stories of meritocractic success even in the most manifestly preposterous setting.” Even Mitt Romney, for example, “tells his own up-by-the-bootstraps story.”

Hayes said that he has succumbed to this impulse himself on occasion. “I think of myself as a scrappy outer-borough kid from the working-class Bronx who has somehow ended up with a TV show,” he said. “And the fact of the matter is I had two college-educated parents who cared a lot about education. I’m a straight white man with a lot of access to privilege.” So “It’s dangerous” to tell these stories, “because it erases privilege.”

Toward the end of the Twilight of the Elites, Hayes homes in not on the poor, but on the middle- and upper-middle classes. “The poor and working class have already suffered through a long period of institutional failure” as a result of wage stagnation, deindustrialization, and deunionization, he said. “That’s been a fact among those communities and in that cohort for awhile.” But those near the middle are only just now seeing just how bad a deal they are in for, just how severely their futures have been compromised for the benefit of a tiny sliver at the top. That’s why insurrectionist organizations like the Howard Dean presidential campaign, and, more recently, the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street have been flooded with their ranks.

These—the once-privileged Americans who are seeing their opportunities get stripped from them—are the people who have “experienced the fail decade most viscerally,” as Hayes puts it. And he thinks they’re our best hope for climbing out of it.