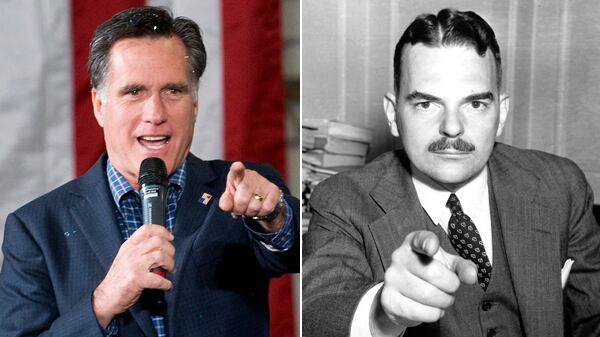

Is W. Mitt Romney morphing into Thomas E. Dewey, the 1948 Republican nominee who famously—and surprisingly to everyone except Harry Truman—was confounded and defeated by Truman’s populist campaign?

Look at Romney’s response to Obama’s profoundly decent and politically adroit decision to stop deporting young people brought illegally to the U.S. as children and instead grant them renewable two-year work permits. Romney, who in his pandering pursuit of GOP primary voters, endorsed the party’s adamant refusal to move the DREAM Act through Congress—and who himself called for “self-deportation”—criticized Obama’s decision, but wouldn’t answer whether he would reverse it as president. He knows he won’t ever be president with his present paltry 27 percent of the Hispanic vote, so he’s been “studying” Florida Sen. Marco Rubio’s half-baked, half–DREAM Act that provides no path to citizenship.

Neither does the new Obama policy; much as he favors a path to citizenship, the president went about as far as executive authority can go—right up to the edge. Romney couldn’t praise him; that would offend the base. Nor could he outright blast the policy; it’s too close to Rubio’s yet-to-be-introduced legislation.

At first, Mitt lamely retreated to bromides about process and a throttle-bottom comment that this “is an important matter to be considered.” Then a newly minted Romney staffer sent out an on-the-one-hand-this, on-the-other-hand-that statement, which finally, grudgingly conceded, “if nothing else, we also see today, his opinion is the same, essentially in some degree, to President Obama’s.” Syntax aside, the real consideration is the degree to which Romney can afford to alienate Hispanic Americans. Thus, in as opaque a fashion as the campaign could conjure up, he threw them a qualified token that the anti-immigrant ideologues may just barely abide.

Dewey exercised a similar caution in 1948. While Truman was delivering tough talk on big issues—the minimum wage, medical care for the elderly, “the do-nothing-80th Congress—Dewey evaded them. Instead he delivered a major address on water, offering up this compelling thought: “We must…use the water we have wisely and well.”

Maybe the stiff Mitt aptly fits Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s description of Dewey as “the little man on the wedding cake.” But with the postprimary Romney, the resemblance is more than icing deep. He has a 59-point economic agenda—59 points—so many that voters can’t grasp any central, driving idea beyond his spurious, biographical claim that he is a job creator. He doesn’t want them to: he aims to give the Republican right its due—a tax cut that primarily comforts the comfortable—without having to argue the point with Obama. His campaign flacked a hallmark education speech in which the hallmark proposal was vouchers, but determined to avoid contention, Romney never even mentioned the word.

The guiding principle of Romney’s strategy, like Dewey’s, is to decline engagement across substantive dividing lines—not to be drawn into a back-and-forth battle on differences that would disadvantage him. The now tightly scripted candidate relentlessly flees any framing of a choice, as Obama recently phrased it, between “two paths to the future,” each of them mapped out by specifics, by measures of effectiveness, by achieving or denying fairness and economic justice. Never let the predominant question for Americans become Who’s on our side; who’s fighting for us?

Romney is steadfast in constantly casting the election as a one-dimensional referendum on the incumbent president. That’s pure Dewey. The Detroit Free Press expressed the rationale for his studied evasion and aversion to debating the issues: the public was supposed to dispose of Truman as “a game little fellow, who never sought the presidency and was lost in it.”

After a rough passage at the start, by the election year Truman actually had a pretty good economy. Not Obama—at least not yet. So Romney prefers and prosecutes a referendum not on the president himself, but on how voters feel about the condition of the economy. He tolerates and even traffics with the Trumped-up birthers; on the night he secured enough delegates to formally claim the Republican nomination, he momentarily let their fantasies smudge his message by appearing with the dim-witted, high-voltage Donald. But that is not where he wants to be, except occasionally when he apparently thinks he has to. And it is not how he thinks he can win.

Shorn of the details Romney seldom discusses, his drumbeat appeal is simple. If you are unhappy with things as they are, don’t remember how they got that way—it’s all Obama’s fault. George who? Don’t ever mention him. Don’t compare proposals or weight their efficacy or equity. Here is Romney’s clarion call: just take a chance on something and someone new—the business guy who might do better. As Peter Hart, one of the most respected pollsters in either party, wrote in a memo after a June focus group in Denver, “Mitt Romney is the remainderman candidate of 2012. Voters have little or no perspective on his plans for the economy … (He) is credited for being a businessman.”

And Romney as Remainderman is not a function of mere circumstance, but an artifact of explicit calculation.

His campaign treats other challenges as a brief detour or as background noise. The candidate recoils from questions about his record at Bain, brushing them off with a token nonreply and swiftly pivoting back to referendum. His first attack ad of the general election exploited Obama’s awkward if arguably accurate comment that the private section was “doing fine.” The president meant it was contributing to recovery—to the tune of more than 4 million new jobs. But in politics, when you have to talk about what you meant, it means trouble. The Romney ad makers tore the remark out of context to push their construct of the race: Obama “has had three and a half years. And talk is cheap … if you want to see the result of his economic policies, look around.” Dewey, whose referendum asked who was more presidential, couldn’t have put this latter-day referendum any more plainly.

Romney’s correct that he probably can’t survive a contest focused on his opposition to rescuing the auto industry, his self-enriching job destruction in the private sector, or a GOP House of Representatives that has blocked bill after bill to spur growth. He’s on the losing side on whether the top 1 percent should pay their share of taxes—and whether Medicare should be privatized. But as Dewey learned, the flight from specifics—a single-toned call to a plebiscite on the incumbent or the country’s condition—can be perilous. Truman forced the cutting-edge issues to the forefront. And he started with an acceptance speech at the Democratic Convention, which bluntly proclaimed, “The Republican Party favors the privileged few and not the common, everyday man.”

This year, as summer wanes, watch the two acceptance speeches to see the struggle, the decisive struggle, to mark out the ground of decision on 2012.

Obama will speak his version of Truman. But Romney will go first—with a preemptive defensive pledge to “save” Medicare and to pass “an across-the-board tax cut,” an attempt to dress his plutocratic program in a pleasing linguistic disguise. This will be designed primarily to fend off attacks, not to win votes. The heat of Romney’s case will be an appeal to an inchoate sense that it’s time for a change. For all the rhetorical flourishes about American exceptionalism, the implicit message will be that we might as well send him to the White House—that things can’t get worse than they are.

Oh yes they can, the president will reply days later as he etches the dividing lines as deeply as possible into the national consciousness. He will draw the contrasts and tie each of them to an overriding theme—standing up for jobs and the middle class. And he’ll chart a way forward without over-claiming the progress of the past four years. In essence, he’ll say there is a lot done but a lot more to do.

In the process, he’ll prove once again the old truth that “politics ain’t beanbag.” And he won’t be heeding the hand-wringers and would-be handlers in Democratic ranks who are pressing him to refrain from mentioning Bain, to retreat from holding Romney to account, to just replay his 2008 campaign or maybe even run away from his own time in the Oval Office. Truman faced the same kind of critics—including a Dump Truman movement—inside his own party; he ignored them and masterfully executed the counsel of his top strategist Clark Clifford to be “controversial as hell.”

Nor should Obama yield—and he won’t—to clucking in the media about negative campaigning. To paraphrase Truman, he’ll just tell the truth—and yes, they’ll call it negative. Here is another insight to be gleaned from 1948: the established wisdom is often unwise. Dewey’s press secretary conducted an informal poll of the traveling press corps; to a man, and they were all men then, they agreed that slugging it out a là Truman was a blunder.

This year, the battle for definition will continue through an unprecedented ad war and the three presidential debates, which could be more crucial than usual. The debates could seal the character of the election as a choice between “two paths.” Romney won’t be able to escape the questions or the issues he fears to face. And if he conspicuously ducks them, Americans will more than suspect that he’s for the few, not the many—and that he would probably make things worse.

For now, referendum is the Romney strategy—and they’re sticking to it. Once again, like Dewey, they’re confident it will work. As Mark Halperin just reported in Time, “Some Romney advisors sound especially bullish, with one positing that a big win by their side is now more likely than a narrow Obama victory.”

Throughout 1948, that kind of confidence suffused the men around the little man on the wedding cake. It was so ingrained that just days before the voting, Henry Luce’s Life magazine, which was to the Dewey operation what Fox News is to Romney’s, featured the GOP nominee on the cover with a banner headline: “THE NEXT PRESIDENT TRAVELS BY FERRY BOAT OVER THE BROAD WATERS OF SAN FRANCISCO BAY.”

The Dewey boat overconfidently sailed on into the deep waters of Election Day—and promptly sank. The contest ended as a choice, not a referendum.

Dewey does Romney—it has a nice ring to it. And after November, the line might rhyme in history, too.