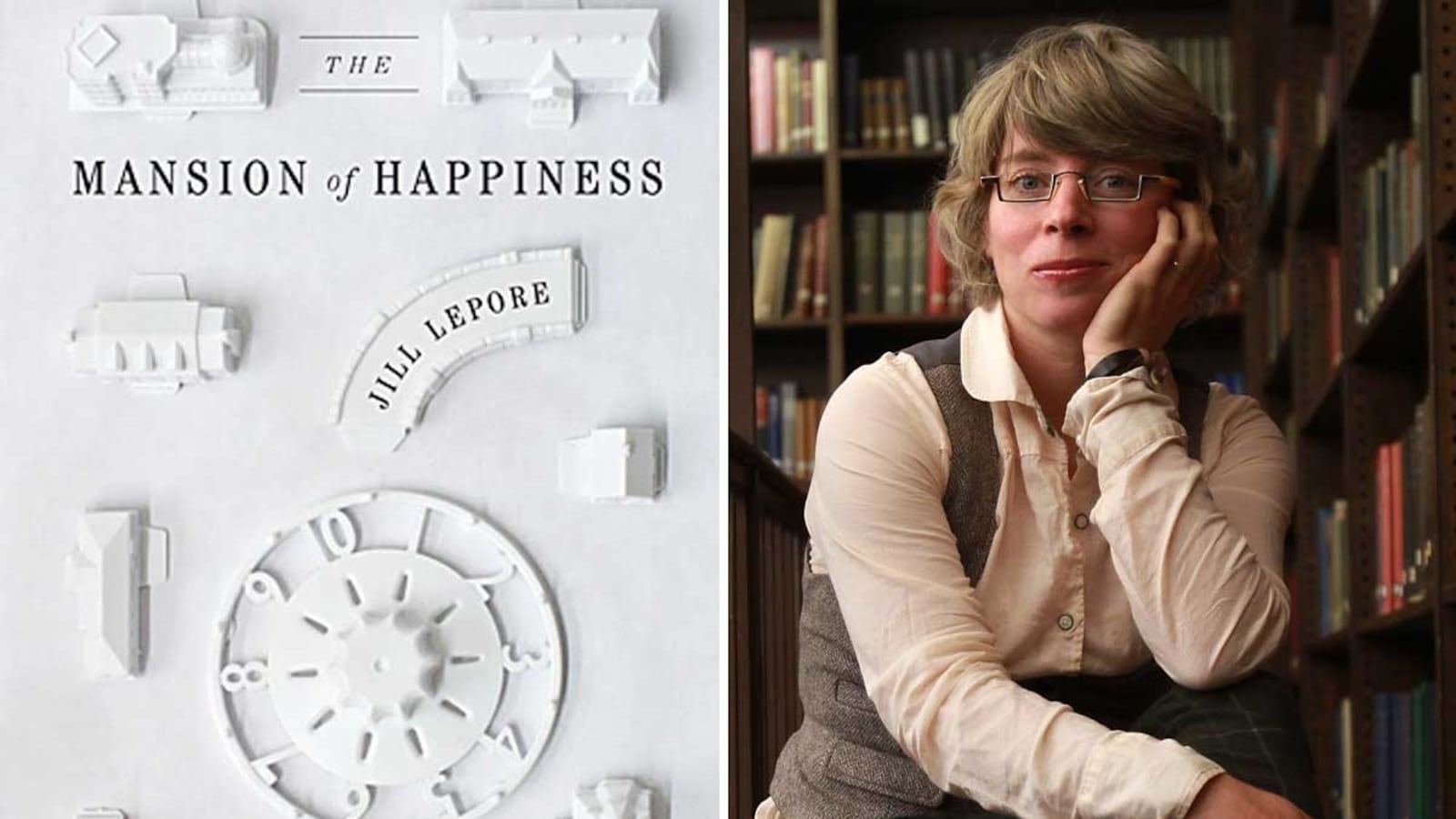

Jill Lepore’s subtitle for The Mansion of Happiness is A History of Life and Death. A more precise description might be, “A series of thoughtful ruminations, observations, and clarifications about various aspects of life and death, mostly as seen through American eyes.” That wording might not sell as many books, but it gets closer to the playfully intelligent if slightly scattershot essays in this work. If you picked up The Mansion of Happiness thinking you’ll be reading a comprehensive history of its subject matter, you’re in for some disappointment. If, on the other hand, you come expecting to be entertained, educated, and given several helpful new ways to think about the stages of life and what lies beyond—and anyone familiar with Lepore’s work knows what a sure bet that is—you’re in for a good time.

A Harvard historian and a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, Lepore has mastered the neat trick of writing imaginatively and often humorously for a general audience without checking her scholarly swing. While she’s surely the smartest person in most rooms she enters, she wears her intelligence lightly and almost never pulls rank. Her last book, The Whites of Their Eyes, an examination of the Tea Party that concentrated on the group’s tenuous sense of history, could easily have been a hatchet job. Instead, Lepore took the trouble to actually go out and talk to party members, and in those meetings she never condescended or mocked them, which is not to say that there was much left of their arguments when she got done.

The Mansion of Happiness examines the stages of life from not cradle to grave but more like fetus to grave. We keep pushing back the point where life begins, a maneuver whose starting point she smartly pegs to Lennart Nilsson’s famous photographs of life in the womb that appeared in Life magazine in 1965. Even the “grave” part is outdated, given that at least some people buy into the idea of cryonics, or frozen corpses that can be defrosted to live again in some crackpot science-fiction future. (Stanley Kubrick took it seriously, although not so seriously that he’s not buried in the English countryside.)

Lepore approaches the territory between conception and death through a variety of inventively conceived portals. Her examination of our changing ideas about childhood, for example, concentrates on a history of children’s rooms in libraries and the relatively new genre of children’s literature—new, at least, since the 18th century. She begins with a mini-biography of Anne Carroll Moore, the New York City librarian who singlehandedly created children’s libraries. Moore was something like urban planner Robert Moses, a visionary who calcified into a tyrant. Her last, futile battle was fought over E.B. White’s Stuart Little, the story of a mouse born to a human family that so disturbed the autocratic Moore that she used all her considerable influence to keep the book off the shelves of school and public libraries. White was unafraid to broach the notion that life is not only mysterious but sometimes completely inexplicable. Moore was having none of that. In the surviving fragments of a letter she wrote to White, she accused him of blurring the division between reality and fancy. (“The two worlds were all mixed up,” she wrote.) White thought children could tell the difference without adult assistance, and there the battle line was drawn.

We all know who won the fight over Stuart Little, but the story is fascinating. It shows how fiercely we fight over our conceptions of what a child is or isn’t. But the essay’s real shrewdness lies in its use of Moore as a person with good ideas and mostly pure motives, whose thinking was overtaken by time and who outlived her usefulness. Like so much of what we think of as the stages of life, childhood is not a fact but a concept. Examining how that concept changes over time tells us much about the evolution of human society.

Luckily for her readers, Lepore approaches all this with a well-honed sense of humor and a deep-seated loathing for pop-psych cant. “Stages of life are like artifacts,” she writes. “Ideas with histories: the unborn, as a stage of life anyone could picture, dates only to the 1960s; adolescence is a useful contrivance; midlife is a moving target; senior citizens are an interest group; and tween-hood is just plain made up.” Her chapter on adulthood takes the form of an examination of our idea of work, specifically the pseudo-science of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s time-motion studies. A lot of what Taylor postulated has been debunked, but his specious influence lingers. Lepore dubs him “by any rational calculation, the grandfather of management consulting.”

When she gets through with Taylor, there’s not much left. But here as always she cautions us, at least implicitly, against sneering too quickly at history’s discredited heroes and their ideas. Even at her most dismissive, as in the passages on eugenics (“a colossal misunderstanding of science and a savage misreading of history”) she takes the time to remind us that not a few respectable people, including Margaret Sanger and Woodrow Wilson, bought into it. As taught by Lepore, history is a lesson in humility.

Her only disappointing chapter is the one on death, and only because she leaves so much out and concentrates instead on the ludicrousness of cryonics. She wants to argue that in the quest for immortality, there’s not much distance between anti-wrinkle cream and freezing a corpse. But surely there is. One is just postponing the inevitable, while the other seeks to deny that inevitability outright.

On her way to visiting Robert C.W. Ettinger, the foremost proponent of cryonics, she pauses at a graveyard and visits a couple of tombstone companies. I wish she’d lingered, because there is no better place to study our changing ideas of death than a cemetery. For just one example, Philippe Ariès observes in his monumental work, The Hour of Our Death, that gravestones in the colonial era were often topped with Death’s head. Over the course of a couple centuries, as our conception of death softened and became more hopeful, those skulls morphed into angels and suns. If I had not read Lepore, I might not have remembered Ariès. That detail is precisely the sort that she uses to illuminate her arguments elsewhere in this marvelous book. Put another way, she gets you thinking like she does, and you can ask no more from a historian.