Welcome to the policy-free campaign.

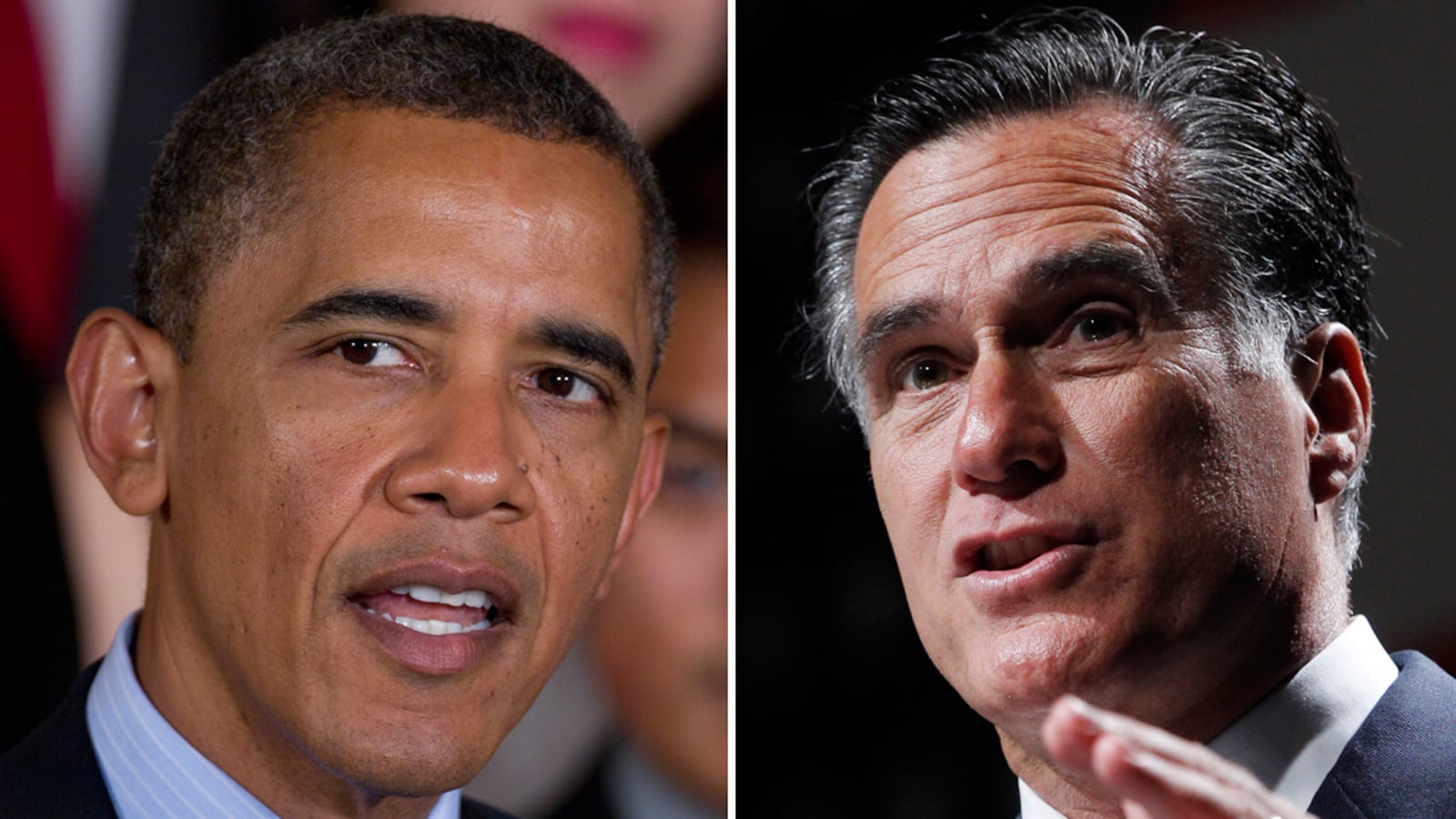

The Romney camp hopes to make this election a referendum on President Obama—it offers the chance to win by default. In contrast, the Obama camp is fervently trying to make the election a choice between the two candidates.

That’s why Romney has been mealy-mouthed about President Obama’s executive action on immigration that effectively implements a modified version of the DREAM Act, sidestepping the issue again in his speech to Latino elected officials in Orlando on Thursday.

The speech was elegant but evasive, inclusive in tone but inconclusive in terms of actual policy. When it came time to comment on the DREAM Act move by the Obama administration—a policy that Romney pledged to veto in the primaries—here is what he said: “Some people have asked if I will let stand the president's executive order. The answer is that I will put in place my own long-term solution that will replace and supersede the president's temporary measure.”

That means precisely nothing. It gives the impression that Romney backs comprehensive immigration reform, which he criticizes President Obama for not advancing. But of course Romney intensely opposed the bipartisan McCain-Kennedy comprehensive immigration bill backed by President Bush in 2007.

The specifics that Romney did offer in the speech—like giving green cards to immigrant university graduates, expanding E-Verify or giving illegals who serve in the military a pathway to citizenship—are already backed by President Obama, with varying degrees of success. Others, like Romney’s call for a high-tech fence along the border, were already implemented by the Bush administration and in that case abandoned after Boeing wasted $1 billion of taxpayer’s money and couldn’t get the technology to work.

And then there’s this howler: “The president hasn't completed a single new trade agreement with a Latin American nation.” Apparently, the candidate hasn’t heard of the Panama or Colombia Free Trade agreements. Fact-checkers should have a field day.

But accuracy isn’t the point when you’re dealing with bumper-sticker policies—narrative is unfortunately more important than facts. And so we all get a little stupider, day by day, during this campaign.

In some ways, the speech was a microcosm of a strategy we’re seeing over and over in this campaign: attack your opponent but avoid saying what you’d specifically do differently to solve the problem.

“Generally, it feels like a campaign about who you don’t want to lead you,” says former Indianapolis mayor and Harvard Prof. Stephen Goldsmith, who was chief domestic policy adviser to George W. Bush in 2000. “In such a ‘gotcha’ polarized negative campaign, making bold policy pronouncements can seem like an unnecessary political risk. This inhibits the willingness to talk about policy specifics because it might make you a target. And that leads to a much less substantive campaign.”

President Obama has so far failed to lay out a compelling argument about how a second term would be different and better than his first one. He hasn’t offered a plan to overcome congressional obstruction or explained how he could achieve a grand bargain on long-term deficits and debt this time around. But in contrast to Bill Clinton’s 1996 playbook, which concentrated on small-ball policies like school uniforms, Obama has advanced big-brush policies that resonate deeply with the liberal base, like marriage equality and effectively implementing the DREAM Act.

The president’s tendency to expeditiously timed conversions has notably increased in the past few weeks, as national polls have tightened.

But a look through Romney’s policy pages online offers little beyond boilerplate. He’s published an agenda for the first 100 days, but it is dominated by campaign-driven contrasts like the Keystone XL pipeline or ambitious-sounding bills that have very little chance of passage.

Romney’s troubles are symbolized by the fact that the most passionate policy difference between the two parties is health-care reform—and, of course, Romney’s key legislative accomplishment as governor was to implement just such a plan. The only way to square that circle is to attack "Obamacare," promise to repeal it on day one and act exasperated when anyone brings up the logical inconsistency, or asks what exactly would take its place. Problem solved?

Likewise, a look back at the GOP primary shows that Romney’s new policies—like his tax plan—were put forward in reaction to other candidates gaining traction. Politics is driving policy in the Romney camp more than personal conviction.

The core policy pitch of the Romney campaign is fiscal responsibility, and the slogan “we have a moral responsibility not to spend more than we take in” is at the top of every policy page of the campaign website. But in an essay titled “How I’ll Tackle Spending, Debt” it’s evident that Romney’s plan doesn’t even begin to add up. He offers a list of base-pleasing spending cuts to “Obamacare,” Amtrak, the National Endowment for the Arts, Title X Family Planning and “ending foreign aid to countries that oppose America’s interests.”

Well, we did the math and even with the most extensive cuts in these areas, Romney would cut about $102 billon from our $15 trillion debt. And even that commitment to fiscal conservatism takes a hit over on the national-security-policy page, where Romney promises to block any scheduled sequestration defense cuts and instead pledges to make military spending 4 percent of GDP—which would increase the budget by some $112 billion. In other words, his spending pledge would negate all the spending cuts he’s pledged to make.

So we’re back to baseline. It’s just shuffling the chairs on the deck of the Titanic, in this case to please the defense-contractor lobby.

In the realm of foreign policy, Romney’s daily invocation of Obama’s alleged “apologizing for America” is done against the backdrop of crisis in Syria and Iran. The president is reflexively accused of being weak on these countries but the Romney policy pages actually advance few concrete ideas other than what is already being done. The key difference seems to be style, not substance.

“This is pablum, nonsense. There aren’t any cutting-edge, fresh ideas” being offered by the candidates, says Melik Kaylan, who covered the Mideast for The Wall Street Journal and now does so for Newsweek International. Romney seems to be advancing policies that are already in place. There is plenty of room for foreign-policy innovation, but those ideas don't seem like they're being embraced.”

Romney has one clear policy edge on Obama that he could credibly advance—his administration would not be beholden to unions. He could advance education reform, entitlement reform, or expand skilled-worker visas more than President Obama ever could. That is a message that might rationally resonate with independents, because it is rooted in fact.

Obama’s best argument is the elephant in the room: behind Romney’s attack-and-dodge strategy is the stark fact that the GOP nominee’s key advisers and basic policies are very much in line with the last Bush administration. Romney is no radical; he is the candidate of the Republican establishment. But that’s a tough sell to voters who aren’t exactly demanding a return to the foreign and fiscal policies that helped create the chaos of the past half decade. So the response is to attack the Obama administration relentlessly without offering specific fixes and hope that no one notices or much cares.

The strategy that has worked before. Witness Richard Nixon’s “secret plan to end the war” in Vietnam as a candidate that became an escalation of it once he was in office. Or FDR’s opaque promises to end the Great Depression and rhetorical nods toward balanced budgets followed by a post-election vacation on Vincent Astor’s yacht.

For voters, the key question is what the next president will actually do in office. That’s why policy matters, especially for challengers. The addiction to negative attacks offers heat but no light. After all, pointing out a problem is very different from having a plan to solve it.