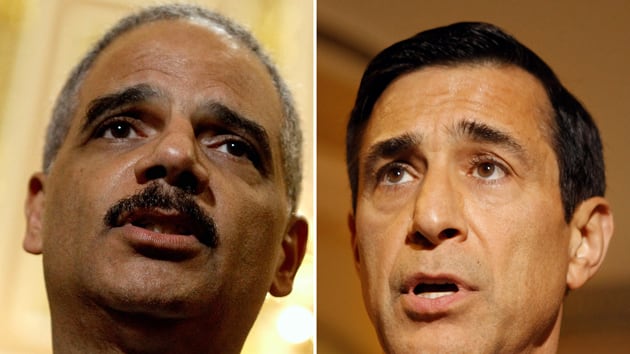

The duel between Darrell Issa and Eric Holder is the latest chapter in a checks-and-balances story that traces back to an epic 1796 showdown between James Madison and George Washington. Courts should stay clear of this duel. Its proper umpires are not life-tenured judges, but ordinary citizens.

Recall that Congressman Issa, backed by fellow Republicans in a key House Oversight Committee (and only by Republicans—more on that later), is demanding that Attorney General Holder produce Justice Department documents that Issa believes will evidence executive-branch bungling and/or dishonesty. In particular, Issa wants documents that explain why Holder and his aides originally offered erroneous testimony to Congress and then later decided to retract that testimony.

Holder is resisting Issa, claiming that he needs to protect internal executive-branch deliberations. Much as justices need to confer confidentially among themselves and with their clerks before issuing their official court opinions, executive-branch officials need some confidential space to candidly formulate executive-branch policy. If these conversations can easily be subpoenaed and publicized by a separate branch, candor within the executive branch will suffer. Officials will end up whispering to each other secretly rather than using emails and memos, and the ultimate policy may end up being less carefully considered.

This isn’t just Holder’s view; the president himself has officially invoked “executive privilege” to resist the latest round of subpoenas.

So who is right? The explicit words of the Constitution itself don’t provide clear answers. The terse text nowhere explicitly provides for “executive privilege”—and also nowhere explicitly provides for congressional “oversight” as such. The text does not even say that Congress has power to subpoena witnesses or punish no-shows.

But the Constitution’s overall structure and two centuries of traditional practice do provide strong guidance. Beginning with the First Congress, each house has asserted broad inherent power—that is, unenumerated power, implicit power, the kind of power that “strict constructionists” and Tea Party types claim the federal government lacks entirely—to oversee the functioning of the executive branch, backed by the implicit power to issue subpoenas and to hold noncompliant witnesses in contempt. On the other side of the ledger, when James Madison and other House leaders demanded that the Washington administration hand over various diplomacy-related documents for inspection in 1796, Washington refused, and the House backed down, establishing an early precedent in favor of executive privilege in certain situations.

Washington prevailed in 1796 because he ultimately had public opinion on his side. And in the Issa-Holder duel, public opinion should and will ultimately decide the matter.

One important element of this duel, however, is not currently well understood by the public: what, exactly, does it mean to “hold” someone “in contempt”? For example, many of Holder’s supporters doubtless hold Issa in contempt, in a manner of speaking. But if Issa is ultimately backed by Speaker John Boehner and a majority of the House, then the House is legally empowered to hold a defiant witness in contempt in a far more literal way: the House may hold a witness in its hold: in a prison cell in the Capitol itself. And the House can keep the witness there, using its own enforcer—its “sergeant at arms”—until the House session ends. And in fact, each house of Congress exercised this power early on in our nation’s history.

But if Issa and Boehner tried to hold Holder, the optics would be ugly, and Mr. Chairman and Mr. Speaker would risk alienating fair-minded voters. Also, no House has ever tried to hold the president himself—commander in chief of the U.S. Army—or a cabinet officer. And any House attempt to hold Holder would be particularly awkward, as it would effectively undo an appointment made by the president and the Senate—an appointment process in which the Constitution pointedly excludes the House itself.

Issa and Boehner are not, however—at least not yet—threatening to lay hands on Holder. Instead they want to issue a “contempt citation” against Holder that will supposedly oblige Justice Department prosecutors to begin a process of judicial punishment of Holder.

But this is all just cheap talk. For the attorney general and all lower-level U.S. attorneys in the Justice Department are executive-branch officials who ultimately answer not to Issa or Boehner or the House sergeant at arms—but to the chief executive, Barack Obama, who has already made clear that he sides with Holder. So the AG and all other prosecutors in the Justice Department are entitled to disregard the House “contempt citation.” The paper has no more authority than a competing piece of paper written by Holder saying “I have contempt for Issa and Boehner.”

Ultimately, courts should stay out of this knife fight altogether. This is a legislative-executive tussle—a classic “political question” beyond the proper province of the judiciary. For the Constitution gives Congress itself the means necessary to deal with a dishonest and/or corrupt cabinet officer. It’s called impeachment.

But if Boehner and Issa do pursue this constitutionally proper path, then their failure to attract any support from their Democratic colleagues may ultimately doom their efforts. Even a House impeachment means nothing—just more cheap talk—unless the Senate actually convicts. And this conviction requires a two-thirds vote, a vote that cannot happen unless Senate Democrats turn on Holder. So if Boehner and Issa are serious, they must either convince some Democratic colleagues to join their crusade or persuade the great middle of the country, comprising millions of fair-minded voters, that there are real witches here that need to be hunted.