In 1993, while working on the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph’s obituaries desk, Kate Summerscale received a letter from a woman suggesting that her godmother, Marion Barbara Carstairs, might make a good subject for an obituary. “Joe’” Carstairs was a motorboat-racing lesbian American heiress who dressed like a man and ruled the Bahamian island of Whale Cay, a worthy subject of an obituary, but an even worthier one of a biography. Piecing together what details she could of Joe’s extraordinary life, Summerscale found herself wanting “to fill the delicate gaps that characterize obituaries”; to work out “why Joe Carstairs lived as she did” and “how the world worked upon her.” The Queen of Whale Cay, the fruit of Summerscale’s labors, was published four years later to great acclaim.

Confirming her considerable skill as a biographer, Summerscale’s follow-up, The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher, was a runaway success both critically and commercially. It was the story of a real Victorian country-house murder featuring all the necessary ingredients of a page-turning whodunit: a dead child found in the privy with a slit throat, secrets lurking behind the polished exterior of a supposedly respectable middle-class family, and the most celebrated detective of his day, Mr. Jack Whicher of Scotland Yard.

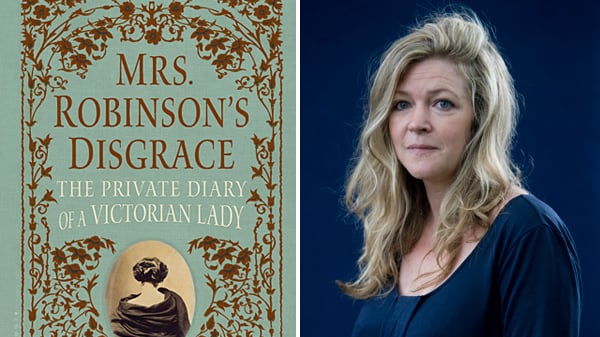

Here, in her third book, the newly published Mrs. Robinson’s Disgrace: The Private Diary of a Victorian Lady, Summerscale brings us another real-life tale of scandal from the mid-19th century, but this time she’s dealing with the crimes of lust, sexual delinquency, and adultery. Half intimate memoir, half courtroom drama, Summerscale brings to life the story of one Victorian woman’s desperate attempts to alleviate the ennui and suffocation of a “barren provincial life” trapped in a loveless marriage.

She first came across the story of Mrs. Robinson in a book about Victorian crime and sensation fiction. In that book, she tells me, the author declared that nobody knew what became of the people involved in the case, a claim which, she confesses, was like somebody “throwing down a gauntlet.” Summerscale attacks her subjects as a self-confessed “novice,” regarding her research as an “adventure” in which she’s more “surprised, intrigued, and delighted” than perhaps a professional historian would be, always “eager to find out more” about the context in which her characters lived, “exploring” her subject, rather than “informing” her readers. Despite that she initially thought the story of Mrs. Robinson was “too small to make a book,” something about the case kept “nagging” at her, so she began to research it, with, it transpires, astonishingly productive results.

Isabella Robinson, wife of Henry Robinson, was 37 when she met Edward Lane, a lawyer turned doctor 10 years her junior who was married with one son. Having already been widowed at age 29, when her first husband died of a “diseased brain,” Henry was Isabella’s second husband, an industrialist she describes in her journal as an “uncongenial partner ... uneducated, narrow-minded, harsh-tempered, selfish, proud.” Isabella was enchanted by Edward, and so began an attraction and eventual romance between the two that she documented in all its uncensored glory in her journal. Six years later, in 1856, two years after the supposed affair had begun, Isabella lay in her sickbed delirious with what appears to have been diphtheria, moaning out the names of men other than her husband, who, with his suspicion aroused, sought out her diary and read the damning confessions therein. Looking back with hindsight, Summerscale admits that she’s “drawn in” to her stories by single powerful scenes; there was something “hyperreal” about this particular episode in the Robinsons’ narrative, she tells me: “It was like it had been lifted from a novel, and I wanted to find the rest of that novel.”

Until this point in the story, the plot is fairly straightforward, a woman trapped by the conventions of her time whose disregard for her marriage threatens her with disgrace—and Summerscale duly notes the parallels to Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, which was then scandalizing France—but the court case that ensued after Henry lodged a petition for divorce gives their story a complicated legal puzzle that made Isabella a degraded victim. All of this is set against the gradual opening up of divorce in Britain to the middle classes with the landmark Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857.

Isabella’s diary was proof of her own lust, but as evidence of Edward’s adultery it was considered inadmissible in court. If used against her, and not him, the case against Edward could well be dismissed but Isabella still found guilty. This would, Summerscale points out, “render the moment of their intimacy at once real and unreal, a fact and a fiction.” The question then posed was whether Isabella’s diary could be the mere ramblings of a nymphomaniac, “pieces of personalized pornography” dreamed up by a sex-obsessed sufferer of the conveniently broad-spectrum uterine disease? Surely a respectable bourgeois wife and mother would have to be mad to even consider diarizing such wanton behavior. Was Isabella the “predatory and aging seductress” that Henry’s barrister alleged, the “rhapsodical and vapouring fool” her supposed paramour claimed was laboring under “moonshine lucubrations,” or just a woman wronged in love?

Given that she had reams of material in terms of extracts from Isabella’s diary and the records of the court case at her disposal, in one way, what Summerscale’s written is, she explains to me, a “more intimate book” than her previous ones. But, in a similar manner to the way in which Isabella’s diary both condemned and exonerated her, so too the document was something of a double-edged sword for Summerscale herself: both her direct access to Isabella’s “raw and unfiltered emotion” but at the same time “the ultimate untrustworthy source.”

What is particularly interesting about the book is the way that Summerscale engages with her material in such a psychologically rich manner, an added bonus feature, as it were, given that the original story is already so fascinating in itself. Radically, but not unconvincingly, she analyzes the arguments that played out in court as condemning diary writing as sexual transgression: “If masturbation was a sexual communion with the self, diary-writing was an emotional communion of the same kind ... In their efforts to save Edward while condemning Isabella, the lawyers had come up with a sex act in which she had been able to indulge without the participation of any man.” Thus allowing her to unlock the door to the then still dark continent of female sexuality and emancipation in a time when a man could secure a divorce from his wife based on proof of infidelity alone, while a woman was forced to establish that her husband had not only been unfaithful, but that he was also guilty of desertion, cruelty, bigamy, incest, rape, sodomy, or bestiality.

The “small” story Summerscale initially envisioned actually turned out to be something much bigger and “richer.” Mrs. Robinson’s Disgrace is a glorious evocation of both one woman’s inner world, her hopes, dreams, disappointments and desires, and her outer one in the form of the painstakingly researched Victorian world she inhabits where a multitude of new ideas are threatening traditional conventional values. When I ask her about the who’s who–like quality of the walk-on parts in the story—from Victorian heavyweights like Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin to the novelists Catherine Crowe and George Eliot—she admits that she too was “amazed” at how many interesting figures and ideas she “bumped into just by following the leads in the diary and the court case”: “I had no idea when I started out that these people, Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, knew anyone of any significance. As far as I could tell at first, they were an obscure undocumented middle-class couple.” Not so anymore, however. Mrs. Robinson’s Disgrace is an equally captivating read which will surely catapult its heroine into the same limelight as her detective predecessor.