Success frequently comes at a cost. People get stepped on. Others get left by the wayside. Marcus Samuelsson, the celebrity chef, knows this better than most.

Shortly after getting out of school, at the beginning of his professional odyssey, he made an enormously stupid decision. One night, in Bad Gastein, Austria, where he was working at a restaurant, he had sex with a young woman and failed to use protection. She became pregnant, and though Samuelson agreed to make monthly payments for his child, it was years before he stepped up to the plate and truly became the girl’s father.

During his 20s his grandmother died, and although she was a crucial figure in his life—the first person who really taught him about food—he was away working on a cruise ship and did not come home for her funeral.

Nor did he show up when his father died, and he was by then the chef at Aquavit, a much-lauded Swedish restaurant in New York that Samuelsson took over in 1994 at the age of 24.

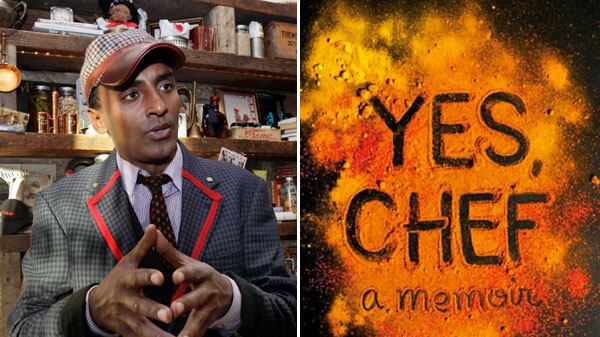

But it did not take a private detective or a biographer like Walter Isaacson to uncover these transgressions. Instead, they are presented to us by Samuelsson himself, in a new and frequently exhilarating memoir, Yes, Chef.

As Samuelsson tells it over lunch at his celebrated Harlem eatery, Red Rooster, he wouldn't have it any other way. He’d been a huge fan of Andre Agassi's memoir, Open (in which the former tennis player detailed with amazing candor his struggle with drugs) and Gabrielle Hamilton’s Blood, Bones, and Butter (in which the chef of Prune discusses everything from stealing as a teenager to carrying on an affair with a woman while married to a man.)

In both instances, he felt, the ability to reveal things that were uncomfortable was what made the books work.

“The only way to get close, is to be honest,” he says. “No victory lane stuff.”

Thankfully, Samuelsson’s book isn’t just a dark, emotional journey about learning to be a man and taking responsibility for your mistakes. It’s also an unabashed piece of food porn and a comedy about what it’s like to climb the ladder in a business that’s as dangerous as boxing and as cruel as ballet.

The story begins in Ethiopia, where his mother fed him and his older sister nothing but shiro, a chickpea flour you boil that’s “kind of like polenta.” When Samuelsson was 3 years old, a tuberculosis epidemic hit, and his mother died.

He and his older sister moved to Göteborg, Sweden, where they were adopted by a pair of white academics with liberal ideas about self-determination and the importance of following your dreams. Neither were great cooks, but his grandmother was, and Samuelsson quickly caught the bug.

“My grandmother didn't die poor, but the majority of what she did was very frugal,” he says to me. “If we had a chicken, she’d make a roast chicken, chicken soup, and chicken dumplings, because that was the thing you did. ‘What do you mean I'm going to throw the bones out? I’ve got perfect chicken liver here.’ I make a liver paté and that's what we need.”

As a teenager, it became clear he would never realize his dream of becoming a professional soccer player, so he applied and was accepted to a vocational high school for cooking, where he learned English and how to make a flawless soufflé.

Soon after, he found work in the kitchen of Belle Avenue, a well-known restaurant in Göteburg—one of his first experiences was watching a colleague slice his finger off; as he describes it in the book, the crew basically carried on as if nothing had happened. Soon after he began traveling the around the world.

At 24, after the chef at Aquavit died of a drug overdose, he became head of the kitchen and soon received a three-star review in the Times from Ruth Riechl, who praised everything from the chilled tomato soup to the pan-roasted venison with lingonberry sauce.

He was the youngest chef ever to receive a rating this high from the Times, and his ascent continued with the relatively well-reviewed Riingo, a pan-Asian restaurant in midtown Manhattan that featured a Caesar salad with tuna and sea urchin, and an omelet that Amanda Hesser said was “cut to look like a geta sandal with a button of rice wrapped on by a strip of nori.”

But in 2008, with the opening of Merkato 55 in New York City's meatpacking district, Samuelsson had his first brush with failure.

And what a failure it was. First, he was trying to bring African cuisine to the United States, where there’s little interest in it. Second was the location—in the meatpacking district, where people often seem more interested in what goes up their noses than what goes in their mouths. “I thought I could slow things down and create this Fellini movie or Scorsese movie within the meatpacking district, and then you can go out,” Samuelsson says. “There was no such thing. That was my bad.”

Also, he admits that the cuisine may have been misguided. “I did a beautiful peanut soup that is a riff on a classic African soup. But if you never had that peanut soup originally, how are you going to understand the riff? I shouldn’t have done that in a club environment, I shouldn’t have taken on a rent that forced us to sell more liquor. I shouldn't have taken on those partners.”

But his considerable social skills and his penchant for appearing on television helped propel him back up, rebuilding his celebrity after Merkato shut down.

Serious foodies continued to snipe that he was not really a master chef, but they couldn’t stop him. In 2009 he was the guest chef at the Obama administration’s first state dinner. In 2010 he won Top Chef Masters on Bravo.

Then, last year, Samuelsson opened Red Rooster, a Harlem hangout that perfectly melded his culinary talents and his flair for bringing people together. There was scrumptious fried chicken, terrific ramen (which he served to me for lunch), a supper club downstairs, and enough celebrity guests, both black and white—David Dinkins, Ralph Lauren, Alicia Keys, Bill Clinton, and Thelma Golden, just to name a few—to rival Bungalow 8 at its height.

“Marcus has opened a restaurant that’s exciting, the vibe is fantastic, there’s a downtown crowd, and an uptown crowd, which is really rare in New York these days,” says Kate Krader, food editor of Food and Wine.

Still, Krader worries about his focus. “The first time I went there, I thought everything was good,” she continues. “There was nothing I didn’t want to have. The last time it was more mixed. The food is a little sloppier when Marcus isn’t there and Marcus has a lot to do.”

Indeed, the day I went, Krader’s entire assessment rang true. Lunch is great, Samuelsson is a little scattered (constantly getting up from the table without quite excusing himself), there is a terrific mix of people (including a former Playboy Bunny now well into senior citizenship who wants to show him old pictures of herself on her iPhone), and everyone wants a piece of him.

Which may be why he winces some when asked the inevitable question of “what’s next?”

“It’s too early in the relationship,” he says, referring to himself, Harlem, and the Red Rooster. “Back in the day, it was all about ‘open more restaurants, open more restaurants.’ I don’t think that’s the volume I want to do. I want to have a meaningful interaction with the public through food and that could be through a restaurant, through nights of high- and low-end dining, through a book, through an online conversation we’re doing with Food Republic, because it’s very important for me to add something that’s good content online. I think that’s next: the online conversation. Why shouldn’t guys know what beer to drink with Chinese food? Why shouldn’t we know which gadgets to use? Ten years ago, it would have been, Are you going to open in Vegas? Now not so much.”

Not that he’s entirely ruling that out. “I have offers every day. If I want to activate that, I can.”