The last thing I expected when I woke up this morning was to spend the day launching a global cyber attack.

So I was surprised by the news that a new type of malware had infiltrated more than 800 computers in Iran and the Middle East. Named Mahdi—after a messianic figure in Islam—the malware is delivered via email attachments, either a PowerPoint presentation of religious-themed photographs or a Word document with a fascinating article about Israel's secret plan to launch electronic warfare against Iran.

I know for a fact it’s fascinating—because I wrote it.

The story, which ran last November on The Daily Beast, reported on Iran’s vulnerabilities to cyber attacks in the event of an Israeli bomb strike on its nuclear facility.

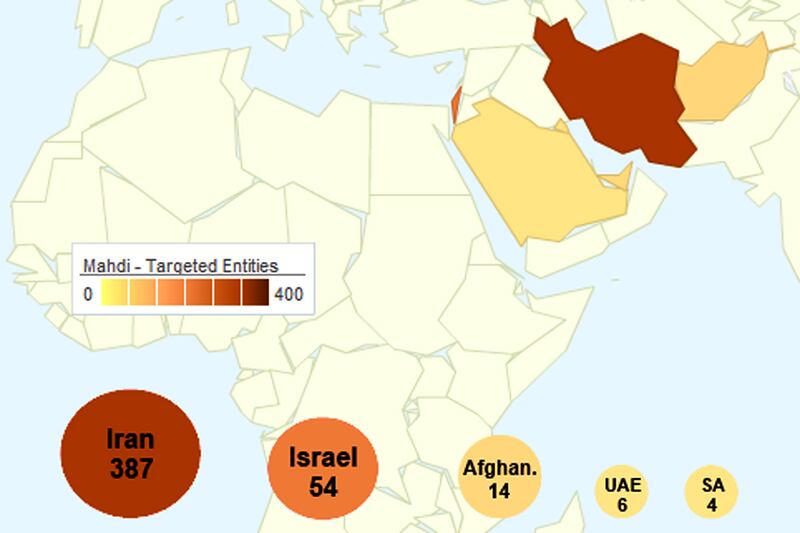

The malware was identified by Russia's Kaspersky Lab and Israeli security firm Seculert. Aviv Raff, the chief technology officer of Seculert, said in an interview that infected computers were found in the United Arab Emirates, Israel, Iran, Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia. Raff said the targets of the attack were engineers, financial experts and other staff attached to embassies.

Raff said he didn’t know who was behind the latest cyber attack, only that the servers controlling Mahdi were based for a month in Iran when the attack was launched in December. After a month, he said, the main servers moved to Canada. Raff said whoever wrote the code likely knew Farsi, the official language of Iran, and used dates from the Persian calendar. He said Farsi phrases appear in the intricate code for the virus.

Iran was recently the target of two super viruses reportedly developed jointly by Israel and the U.S. The Flame virus attacked Iranian computers, turning them into hidden microphones and surveillance cameras. Stuxnet sabotaged centrifuges at a uranium-enrichment facility. In January, Iran announced the formation of a “cyber command” unit of the army to combat cyber warfare.

The new virus is far less sophisticated than Stuxnet or Flame, both of which relied on vulnerabilities in software unknown to developers and the antivirus community. The Mahdi virus seeks to infect computers through guile, by tricking a user with an email meant to look like it comes from a colleague.

This technique, known as “spear phishing,” is a favored tactic of organized crime. China was recently accused of using spear phishing to spy on activists associated with the Dalai Lama.

In a blog post, a Kaspersky engineer explains that Mahdi “relied on a couple of well known, simpler attack techniques to deliver the payloads, which reveals a bit about the victims online awareness. Large amounts of data collection reveal the focus of the campaign on Middle Eastern critical infrastructure engineering firms, government agencies, financial houses, and academia. And individuals within this victim pool and their communications were selected for increased monitoring over extended periods of time.”

As a journalist, I always wanted my stories to change the world. Delivering payloads and attacking critical infrastructure, though? Not exactly what I had in mind.