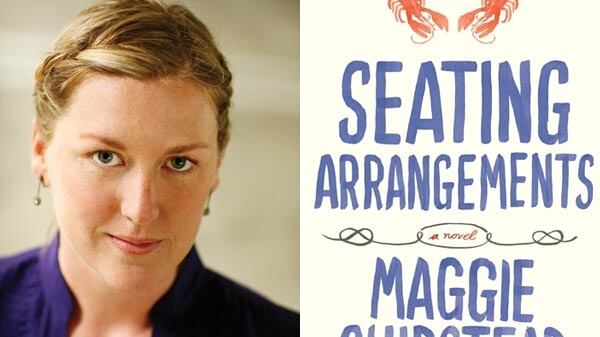

“Literary thinking relies upon literary memory, and the drama of recognition,” Harold Bloom once wrote. Maggie Shipstead’s first book, Seating Arrangements, can be read as a Harvard-tinted, golf-club obsessed WASP comedy about a wedding on an island off Cape Cod. The perfect beach novel, right? But Seating Arragements works at a different level: it’s clear Shipstead is coming to terms with T.S. Eliot (quoted in the epigraph), Shakespeare, Arthurian legends (chapters include “The Castle of the Maidens” and “The Maimed King”), and other mythologies (“A Centaur” and “The Ouroboros”), and connecting it to the American Camelot. (Even the title brings to mind this vital issue: how does Lancelot figure out where to sit at the round table?) This is ambitious, but if you grew up in New England, how many times have you sat on your beach chair with The Once and Future King and a biography of JFK right next to each other, purling these mythologies in your sunned head? Shipstead picks five other seaside reads that offer much more than meets the eye, with her favorite passage from each book.

To the Lighthouse By Virgina Woolf

The Ramsays are having a house party at the beach! What sexy, zany mishaps will ensue? What dark secrets are locked away in this mysterious lighthouse? Well, none, but Woolf’s rendering of the puzzles and conflicts of human perception is awe-inspiring. The magnificently lyrical and melancholy “Time Passes” section is one of the great feats of literature.

Already ashamed of that petulance, of that gesticulation of the hands when charging at the head of his troops, Mr. Ramsay rather sheepishly prodded his son's bare legs once more, and then, as if he had her leave for it, with a movement which oddly reminded his wife of the great sea lion at the zoo tumbling backwards after swallowing his fish and walloping off so that the water in the tank washes from side to side, he dived into the evening air which, already thinner, was taking the substance from leaves and hedges but, as if in return, restoring to roses and pinks a lustre which they had not had by day.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

There are no beaches in this book, but it’s a delicious read: cucumber-cool and, tonally, a marvel of sustained archness. A group of ultra-privileged collegiate aesthetes take their devotion to the study of classical Greek just a wee bit too far and end up committing a terrible crime. If reading on the beach, use this book to conceal (or pointedly semi-conceal) eye-rolling about fratty volleyball antics or less-than-impeccable swimwear.

The third boy was the most exotic of the set. Angular and elegant, he was precariously thin, with nervous hands and a shrewd albino face and a short, fiery mop of the reddest hair I had ever seen. I thought (erroneously) that he dressed liked Alfred Douglas, or the Comte de Montesquiou: beautiful starchy shirts with French cuffs; magnificent neckties; a black greatcoat that billowed behind him as he walked and made him look like a cross between a student prince and Jack the Ripper.

Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier

Told as a reminiscence by the second wife of Max de Winter, widower of the drowned, seemingly perfect Rebecca and owner of a famously splendid house in Cornwall called Manderley, this is a classic of mild-mannered Gothic suspense, full of eerie happenings, sinister housekeepers, and uncanny doublings.

I can close my eyes now, and look back on it, and see myself as I must have been, standing on the threshold of the house, a slim, awkward figure in my stockinette dress, clutching in my sticky hands a pair of gauntlet gloves. I can see the great stone hall, the wide doors open to the library, the Peter Lelys and the Vandykes on the walls, the exquisite staircase leading to the minstrels’ gallery, and there, ranged one behind the other in the hall, over-flowing to the stone passages beyond, and to the dining-room, a sea of faces, open-mouthed and curious, gazing at me as though they were the watching crowd about the block, and I the victim with my hands behind my back.

Loving by Henry Green

If you prefer your beaches cold and windblown and find Downton Abbey sentimental and pedestrian, you probably need to lighten up, but you would also like this book. The wry, tender narrative roves among the staff of a large Irish house during World War II, dropping in on their romances, anxieties, and rivalries. Green was a dialogue wizard of the first order and let the mundane music of his characters’ voices do most of his storytelling. Negative space is used to great effect; the gaps around the characters’ words vibrate with significance.

A silence fell.

“What did you say your sister’s name was?” Edith asked.

“Mum had her christened Madge,” the lad replied. He tried a glance at Edith but she was not regarding him. “To tell you the truth,” he continued, “I did wonder what’s the right thing? I thought maybe you could advise me?” He looked at her again. This time she was indeed contemplating him though he could not make out the expression in her enormous eyes beyond the black yew branch of windblown hair.

He turned away once more. He spoke in what seemed to be bitterness.

“Of course I’m only young, I know,” he said.

The Outlaw Sea by William Langewiesche

Read this book while lying in the sand and you’ll find yourself looking up from time to time to study the blue horizon with new respect and perhaps a thrill of fear. There are lots of possible angles to take on the thesis that the ocean is extremely scary, and Langewiesche’s is the shadowy lucre and lawlessness of commercial shipping. Among other things, the book delves into modern piracy and the horrifying sinking of the Baltic ferry Estonia before ending on the beaches of Alang, India, where ships go to die.

Under its many names, and with variations in color and mood, this single ocean spreads across three-fourths of the globe. Geographically, it is not the exception to our planet, but by far its greatest defining feature. By political and social measures it is important too—not merely as a wilderness that has always existed or as a reminder of the world as it was before, but also quite possibly as a harbinger of a larger chaos to come. That is neither a lament nor a cheap forecast of doom, but more simply an observation of modern life in a place that is rarely seen. At a time when every last patch of land is claimed by one government or another, and when citizenship is treated as an absolute condition of human existence, the ocean is a realm that remains radically free.