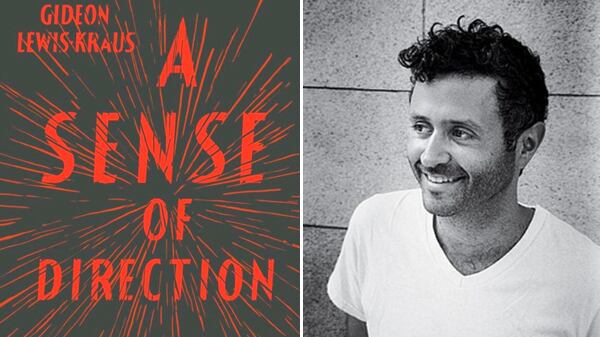

In 1947 Sal Paradise/Jack Kerouac and Dean Moriarty/Neal Cassady went on the road, and their intense quests for meaning embodied the Beats. In 2008 Tom Bissell and Gideon Lewis-Kraus went on a trip around Europe, and their friendship illuminates a skeptical-slacker era exemplified by hipsters in Brooklyn. Their pilgrimage, on foot, forms part of Lewis-Kraus’s travel memoir, A Sense of Direction, with a lone journey to Japan and a trip to Ukraine with Lewis-Kraus’s father and brother rounding out the three acts. Lewis-Kraus talks about writing the entire first draft of his book on his phone with a little foldable Bluetooth keyboard.

I hear you’re a Jersey boy ...

I grew up in New Jersey, of course. My book pretends to be about pilgrimage, but it’s really about restlessness, and nobody feels more restless than somebody from New Jersey. New Jersey is great, and now that I live in New York, I actually go back to see my parents and eat at proper diners all the time, but the main thing about New Jersey is that it is defined by its proximity to somewhere else. New Jersey is the place that is next to a better place. There is pretty much nowhere that’s closer to elsewhere. This makes it chiefly a place that you leave. It’s actually the world’s best place to leave.

Is there any one of your projects that makes you proudest?

I’m extremely proud of [this new] book, which came out much weirder than I expected. When I was in my early 20s and just discovering all the books that have come to be my favorites—Out of Sheer Rage, The Emigrants, The Silent Woman, Move Your Shadow, Armies of the Night, The Orchid Thief, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, The Biggest Game in Town, all of Joan Didion—I realized that the nonfiction that held the most appeal for me was always the really nonclassifiable stuff. But it’s hard to go about writing a nonclassifiable book; if you know what it’s going to look like in advance, it’s probably pretty well classifiable. With this one, I thought I was just going to do a travelogue with some anthropological digressions, but as I went along, the digressions began to take over, and I was like, oh, this is great. I have a book that’s all digressions! Which is the best kind of book. And I was pretty well reconciled to the fact that nothing was really going to come together in the end.

But then I spent a week in a cabin on the Russian River with my best friend, Harriet, who’s a fiction writer. She was like, “You need to figure out how all this comes together in the end.” I said, “But it doesn’t come together, and that’s fine!” She said, “No, no, it does come together.” And then she showed me how. I was like, “Huh, that’s really neat. It does come together after all.” I was pretty proud of that, even though somebody else had to point it out to me. The thing I’m second-most proud of is a forthcoming thing I have that definitively solves the problem of the relationship between cats and the Internet.

Describe your morning routine.

I’ve had a lot of different morning routines over the years. In San Francisco, I used to wake up and go sit and read the newspaper at a café called Tartine. Sometimes I would run into this man who had had a very successful career—he was either a doctor or private-wealth manager, I forget—and then had become a high-end chocolatier, and he and I would trade obscure reading suggestions. In Berlin, I used to wake up and go and have black tea at a Turkish place and read the newspapers there, and no matter how many times I told them I didn’t speak Turkish, they would speak to me in Turkish. When my German was bad, I read the tabloids, and as it got better, I switched to the reputable papers. This was around the time that two different things were dominating the German newspapers: the kidnapping of Germans (hikers on Mount Ararat, oilfield workers in Nigeria) and the constant discovery of new Austrian suburban sex-torture dungeons. So I have a vast confinement-related lexicon in German.

In Shanghai, my brother and I would get breakfast at this great Korean chain called Paris Baguette. There’s one in New York now, but it’s not as good. He and I spent 48 hours in Seoul together a few years ago, and we pretty much only ate at Paris Baguette. At any rate, when I moved back to New York a year and a half ago, I didn’t really have a morning routine, because I would just roll out of bed and start writing. My mornings have gotten very peculiar since I got seriously involved with somebody. She’s always up early and on the phone to her parents, so I wake to a foggy delirium of Italian and Portuguese.

Those are some adventure-packed mornings. Dare I ask about your writing routine? Any unusual rituals associated with the writing process?

I have no writing rituals. When I first started to try to write seriously, when I was 22, I was really precious about the whole thing. Like, I had to wake up at 7, eat a piece of toast, drink one cup of coffee while I read the newspaper and a second cup of coffee while I read something inspirational (which at that time meant rereading a [David Foster] Wallace essay, but these days means rereading Janet Malcolm, usually), and had to be at my desk, ready to write, by 8:30. If any of that didn’t work for some reason—if I was out of toast, say, or had too much coffee—I had to give up writing for the day.

But then I started to get to know Tom Bissell, who, many years later, ended up being one of the main characters in my book, and he said to me, “Look, if you’re going to write, you have to think of it as a job, and a job is something you do even when you’re tired and don’t feel like it and are out of toast, and if you train yourself into precious habits now, you’re never going to be able to give them up.” And, actually, the writing of this book was great insofar as it forced me to learn to write under adverse conditions. I wrote the first drafts, all in the form of emails, from loud, squalid pilgrim hostels and Internet cafés and bus stops and park benches and hotel lobbies, even when I’d walked 30 miles that day.

The reviewer for The Wall Street Journal ended his otherwise really kind, thoughtful review with the suggestion that next time I leave my laptop behind. My response was, first of all, I didn’t travel with a laptop, which would’ve been much too heavy to lug around, but rather I was writing most of that on my phone with a little foldable Bluetooth keyboard, and second of all, what it did was invert, for me at least, how we usually think of our devices: it wasn’t in the service of distraction, it was actually in the service of unbroken concentration. I got to the point where I could take out my little keyboard on a bench, or in a Japanese temple I’d broken into to get out of the weather, and tune out the clatter of hail and the ache in my legs and just work for hours and hours without looking up.

Do you have a favorite snack (one that is not consumed during your elaborate breakfast routines)?

My friend Molly pointed out that the only foods I describe with any real enjoyment in the book are small, portable things. The best example are rice balls, which are these little seaweed-wrapped triangles of rice with a little clod of filling inside, fish or pickled vegetables. You can get them anywhere in Japan; the convenience stores have whole shelves of them, and they’re very cheap and ingeniously packaged to keep the seaweed away from the rice. They also are marked with the hour that they expire. I probably ate like six of them a day. Most days I didn’t eat anything else. When I got back from Japan, my editor was like, “I bet you’re never going to eat those again!” Needless to say, I was like, “Of course I am, you lunatic.” I still eat them all the time, but in New York they’re harder to find. The best ones are near the main branch of the New York Public Library, which was where I wrote the last two drafts of my book. It was convenient, cheap, and a good memory spur.

What do you need to have produced or completed in order to feel that you’ve had a productive writing day?

I tend to work in really mechanical and arbitrary ways. So during the first stages of working on something, when I’m typing up my notes in narrative form, I just write every day until I’ve exhausted my notes. Sometimes that’s an hour, and sometimes that’s six hours, depending on how much reporting I’ve done, which is mostly to say how much living I’ve done. I’ve discovered this completely bizarre fact that I tend to live/report about 2,000 words in a day. It almost always averages out that way for some reason. But that’s only my notes. In the second phase, when I’m reworking my notes as a real draft, I usually just set a daily word count and stick to it; typically, it’s 1,500 words or so, but I’m content if it’s only 1,000, as long as it’s 1,000 that I really like.

In the later phases, like when I was writing drafts four, five, and six of my book, I would map it all out. I remember I decided I was going to completely set aside what I had and start over for my third draft. I printed it out, put it on my desk, and opened a new document. It was the 1st of October. I knew I wanted to go visit my brother over Thanksgiving and I would feel much better about the trip if I were done with another complete pass. So I counted the days I had—it was like 45 days, maybe—and I divided through by the number of words I had (at that point the draft was about 140,000 words, around a third longer than the final turned out to be), and found that I had to write just over 3,000 words a day, every day, to get through the whole thing. So for those six and a half weeks, I stopped every day at the first section break after I’d gotten to 3,000 words. I was writing six or eight hours a day, Internet off, and I was a zombie by the end of the day, but I knew it was for a limited time, and I finished right on time to leave town and not think about the book at all for a week.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

Oh, without a doubt it would be to imitate. Style, in the end, is the failure of perfect mimicry—or, perhaps better, the result of trying to mimic two or more people at once, and thus to have to figure out how to reconcile disparate influences in a way that makes for some ultimate coherence. For the first few years of writing, I would think to myself, in this exercise I’m going to try to sound like Wallace. In this exercise I’m going to try to sound like Dyer. In this exercise I’m going to try to sound like Malcolm. In this exercise I’m going to try to sound like Didion. And so on. And in the end of course I failed utterly in sounding like any of them, but ideally that sort of process of imitation and reconciliation brings you to sound like yourself. That’s all we are, anyway, is a more or less successful process of practiced, ad hoc influence triage.

What is your next project?

The long-awaited solution to the mystery of the relationship between the Internet and cats.