Mitt Romney is at it again. Appeaser, apologizer, blah blah blah. It’s funny, isn’t it, that if Barack Obama is such an appeaser and an apologizer, then why do their foreign-policy plans and ideas—insofar of course as Romney actually iterates any, which is not very far at all—sound so similar? The truth is, they are awfully similar. The only thing that’s really all that different is the rhetorical upholstery that supports and frames those ideas. But this is an important difference indeed, because in foreign policy more than the domestic arena, rhetoric commits a candidate to certain types of follow-through, and Romney’s rhetoric commits us to an idea about America that is out of date, reactionary, and dangerous. But the thing that amuses me is that it isn’t the automatic winner with the public that he undoubtedly assumes it is.

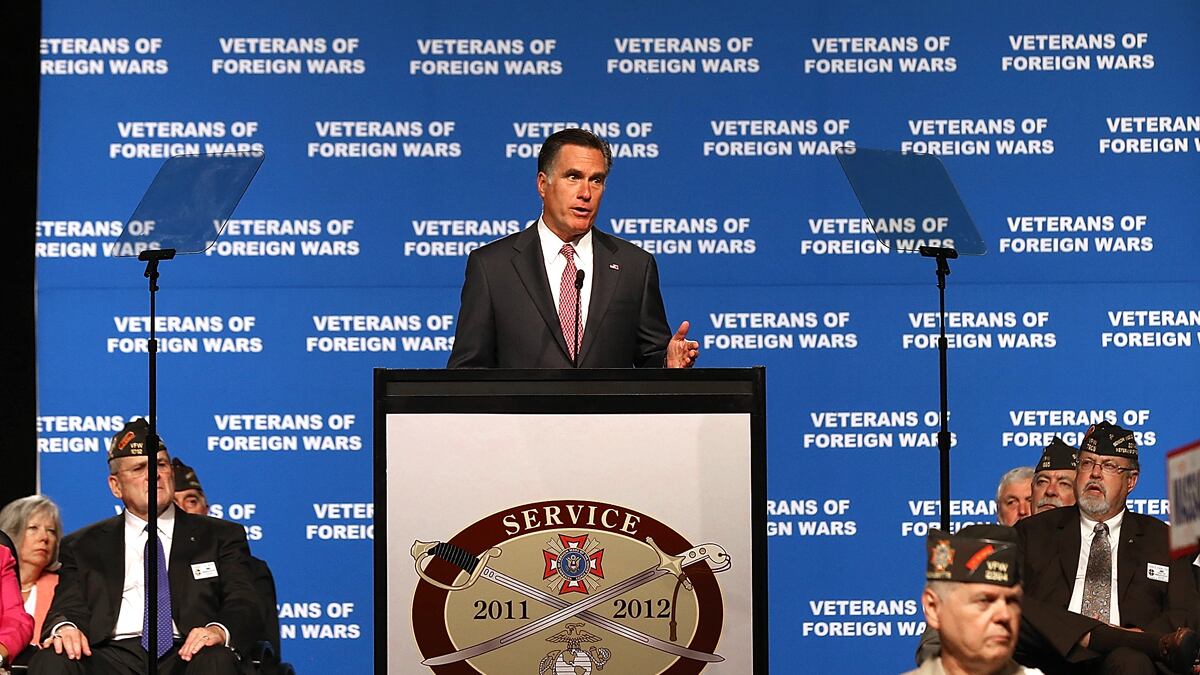

Here’s the nut graf, as we say, of Tuesday’s speech to the VFW: “I am an unapologetic believer in the greatness of this country. I am not ashamed of American power. I take pride that throughout history our power has brought justice where there was tyranny, peace where there was conflict, and hope where there was affliction and despair. I do not view America as just one more point on the strategic map, one more power to be balanced. I believe our country is the greatest force for good the world has ever known, and that our influence is needed as much now as ever. And I am guided by one overwhelming conviction and passion: this century must be an American century.”

Standard American exceptionalism. Again, much of it doesn’t differ from what Obama says—in his VFW remarks, he too went on about the next American Century. The difference between the two, though, rests largely in one word—the way Romney uses the word “power.” His implication in his second sentence above, of course, is that Obama is ashamed of American power. And then in the third sentence, it is our “power”—not our authority, which is a very different thing from power, and not our moral suasion, and not our dollars. Our power.

It’s a grotesque misreading of history and misunderstanding of the successes America has achieved. Our power may have helped defeat the Nazis, although let’s face it, the Soviet Union’s did more to that end. But our authority, moral suasion, and dollars secured the peace in both Europe and Japan. The Marshall Plan, a $14 billion enterprise, rebuilt Europe. In Japan, our power won and emphatically ended the war, all right. But American investments in postwar Japan were enormous, as were decisions like inviting Japan (against some opposition) into GATT, so that its export-based economy could enjoy law tariffs. That part of the world that has remained more or less at peace since 1945, give or take a Milosevic or two, was not stabilized by American power. It was stabilized by American planning, cooperation, and money.

In other parts of the world, of course, our power has been used toward less admirable ends—Vietnam, the coups against Arbenz and Mossadegh, and so forth. You don’t have to be a Chomskyite to acknowledge this. George W. Bush did here and there while he was president, and Condoleezza Rice famously remarked in a speech in Cairo in 2005: “For 60 years, the United States pursued stability at the expense of democracy in the Middle East—and we achieved neither.”

The emphasis on power with no downsides and not being ashamed is a signal to the neocon Project for a New American Century crowd that he’s one of them. It’s demagogic and irresponsible, sure. But at campaign time, I’m more interested in the question of its political efficacy.

Unapologetic American exceptionalism sounds like a winner on the campaign trail, and it’s the kind of big-stick, table-banging rhetoric that really used to scare liberals to death. But does it now? It certainly shouldn’t. It’s the kind of rhetoric that depends on the existence of a widely perceived existential threat that Americans understand they would make sacrifices to defeat. For still more than half of my life, for so long for many of us that it seemed like the natural order of things, there was such a threat. But in 1991, it went away. That’s a long time ago. For those with no living memory of the Commies, there was another mortal threat, delivered to lower Manhattan and the Pentagon in 2001. But that’s receding in memory, too. And when one does remember it, one remembers other things—the toxic with-us-or-against-us culture, the two grinding wars that grew out of it that still aren’t won, wars most Americans now think weren’t really worth the trouble.

The Washington Post found this month that even most Republicans now say the Afghanistan war wasn’t worth fighting. Afghanistan! Of the two, that was the “good” war, the one that at least had the justification of being waged to remove a regime that harbored our attackers (the one of the two Bush wars that I supported). Americans also overwhelmingly favor Pentagon budget cuts—the number one specific item on Romney’s cahier du appeasement against the president. Even about two-thirds of Republicans tell pollsters they take this position. When even Republicans are expressing views like these, how broadly can steroidal American exceptionalism really be resonating out there?

Romney is talking inside a self-reinforcing circle of people who think rattling the saber is irresistible at all times and in all circumstances. But it’s not. I gleefully picture all of them waking up on Wednesday, Nov. 7, mystified about why the American people have not heeded their desperate warnings, while the man in the White House, who has personified the art of walking softly and carrying a big stick, gets back to work.