Sir John Masterman, distinguished Oxford academic, successful sportsman, and veteran spymaster, spent the Second World War running double agents, spies recruited and trained by the Nazis who had been “turned” and persuaded to spy for Britain against the Germans. He found them intriguing, infuriating, and priceless.

“Every double agent is inclined to be vain, moody, and introspective,” Masterman complained. His spies were variously louche, opportunistic, greedy, brave, and idealistic. Many were deeply peculiar, and some operated in that gray area between ingenuity and insanity. Most were to some extent fantasists, and thoroughly unreliable, “persons who have a natural predilection to live in that curious world of espionage and deceit.” Spies are fickle creatures, Masterman reflected, and double agents are doubly so.

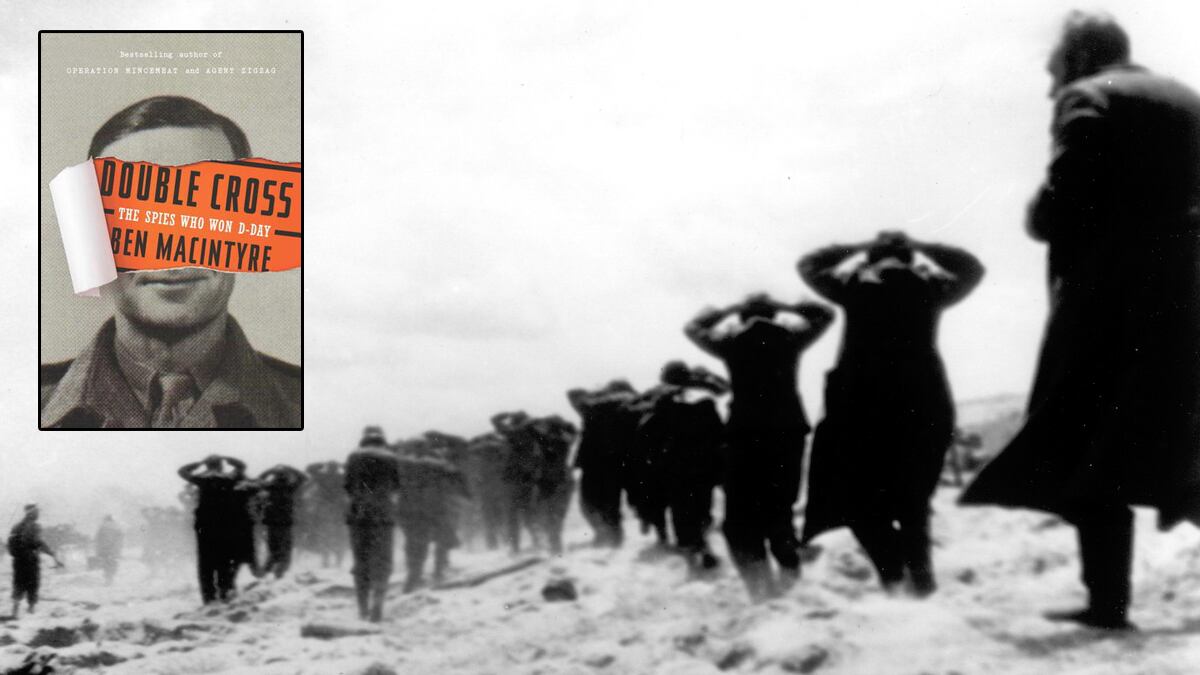

Twenty years after the end of the war, to the consternation of his more tight-lipped colleagues in British intelligence, Sir John Masterman revealed just how much double agents had done to ensure the success of the D-Day landings. Allied victory depended, he wrote, on a bunch of disreputable, two-faced liars, managed by honorable, upright British gentlemen like him.

The double agent remains the most prized, the most feared, and the most unreliable weapon in the espionage armory. Sun Tzu, the ancient Chinese military strategist, stressed the supreme importance of having a spy within the enemy’s spy camp; double agents plied their shadowy trade to remarkable effect during the intelligence duels of the First and Second World Wars, and the Cold War. And double agents continue to play a vital part in the modern intelligence battle that underpins the War on Terror.

In the months leading up to D-Day in June 1944, British intelligence turned a motley team of double agents into a powerful secret weapon that was quite different—and certainly more eccentric—than any used before or since.

This was the “Double Cross” system, operated by the Twenty Committee under Masterman’s chairmanship and so-called because 20 in Roman numerals, XX, forms a double cross. At the heart of system was a team of five spies feeding false information to their German spymasters.

Their codenames were Brutus, Bronx, Treasure, Tricycle, and Garbo, and they were the most unlikely military unit ever assembled: a tiny Polish fighter pilot, a mercurial Frenchwoman, a Serbian seducer, a Spaniard with a diploma in chicken farming, and a bisexual Peruvian playgirl by the remarkable name of Elvira Concepcion Josefina de la Fuente Chaudoir.

Together they changed the course of the war by successfully fooling their German handlers, and therefore Hitler, into believing that the main D-Day landings would take place at Calais, rather than Normandy, where the Allies eventually stormed ashore on June 6th 1944.

The Double Cross deception may sound like something out of fiction. In a way, it was: its practitioners approached the task as if they were writing some vast, multicharacter novel. But the techniques they used are remarkably similar to those still employed today.

In May it emerged that a mole within al Qaeda in Yemen had foiled a plot to blow up an American airliner with a hi-tech bomb secreted in a pair of underpants. This man appears to have been a “coat-trailer” in spy parlance, an agent primed and sent over to the other side in the hope that he will be recruited and can then act as a double agent.

The Saudi-born double agent appears to have "trailed his coat" for at least a year in front of members of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), even enrolling in an Arabic-language school, before being selected and trained to mount the suicide attack. He wormed his way into the confidence of his al Qaeda superiors, and then began feeding secrets back to the CIA and Britain’s MI6. Finally he was tasked with carrying out the bombing and successfully brought the device out of Yemen before handing it over to U.S. authorities.

The Underpants sting was straight out of the Double Cross playbook: but like all such operations, it is likely to have been fraught with anxiety. The double agent in the Yemen operation will have been closely monitored to ensure that he was not playing a triple cross, the nightmare of every agent runner. Spying on your own spy is also a traditional part of the game. The wartime double agents never knew it, but they were kept under constant surveillance to check that they had not "flipped" back to the enemy.

Britain’s wartime spymasters were (rightly) paranoid that one or more of their key agents might really be working for the Germans. One, the Polish spy Roman Czerniawski, had already changed sides twice before he was brought into the Double Cross team. Fearful that he might yet stab them in the back, the British gave him the codename “Brutus.”

Britain’s American allies were also dubious about using such unpredictable human material in such a high-stakes gamble. J. Edgar Hoover, in particular, believed that all spies were vermin, to be caught, tried, and then executed, with maximum publicity. The FBI chief saw little point in trying to “turn” intercepted German spies.

Yet by the time of D-Day, the U.S. had woken up to the value of “doubling” spies, and the FBI was running its own team of double agents from the U.S., plying the Germans with a stream of disinformation to back up the main Double Cross deception operation.

Chief among the American double agents was Jorgé José Mosquera, an Argentinian wheeler-dealer based in Hamburg. In 1941, he was recruited by German intelligence and instructed to make his way to New York, build a wireless transmitter, and begin sending military information as soon as possible. “A tall, pleasant-looking businessman with some glamour effect,” Mosquera promptly gave himself up to U.S. authorities and offered to work against the Germans.

The FBI furnished him with a new identity as “Max Rudloff,” and established a transmitter on Long Island to send messages to Mosquera’s spymasters in Germany. But Mosquera amply fulfilled Masterman’s opinion of double agents as vain, moody, and difficult. He soon began demanding money, and in New York he conceived a grand passion for a much younger woman of Italian extraction who wanted to be an opera singer. He insisted that the FBI hand over $15,000 to enable his lover to pursue her operatic career. The bureau even arranged for her “audition at the Metropolitan Opera,” the first and only time that institution has played an active role in international espionage.

By D-Day the Allies had turned these spies on both sides of the Atlantic into an extraordinarily effective vehicle for passing disinformation to the Germans. They successfully convinced Hitler to keep thousands of troops in Calais following the Normandy landings, awaiting a second, far larger invasion that never came.

The Double Cross operation was hailed as the most successful military deception ever attempted, a remarkable demonstration of the unique British talent for deception, espionage, and subterfuge: Nobody Does it Better

But what the British spy runners did not know, and would not discover until many years after the war, was that their own organization had been penetrated by a spy.

Anthony Blunt was recruited by Soviet intelligence while at university in Cambridge. At the start of the war, on the orders of his Soviet handler, he successfully “coat trailed” his way into MI5. By 1943, Blunt was sending reams of top-secret information to Moscow. Indeed, Stalin was better informed about the Double Cross system than Churchill himself.

James Jesus Angleton, the postwar CIA counterintelligence chief, described espionage as a “wilderness of mirrors,” a world in which reality and lies, loyalty and betrayal, reflect and distort one another to the point where nothing is truly true, and all appearances are deceptive.

Britain’s wartime spymasters understood the extraordinary value of double agents but failed to spot the double agent in their midst.