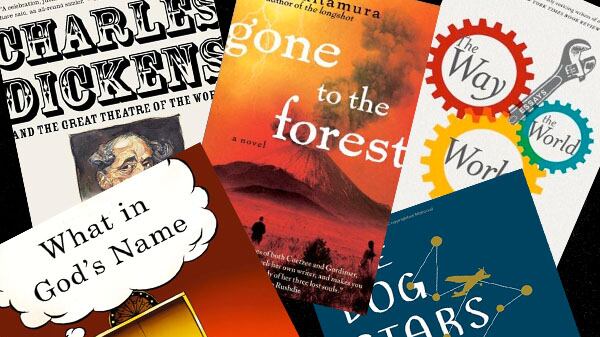

The Way the World Works: Essaysby Nicholson Baker

Baker’s essays suspend you every few sentences or so, as you savor the silence that he creates and enjoy the weightlessness you feel leaping from one thought to another.

Chesterton, Hazlitt, William James, and Samuel Johnson are listed as some of Baker’s heroes of the personal essay. He is far less didactic. I wonder if the author of Vox, The Fermata, and House of Holes—one of the very few contemporary writers able to pull off wildly imaginative and unpedestrian novels—is the heir to Hemingway when he’s writing nonfiction. Baker is the master of the deathly precise, matter-of-fact observation, as when he writes about videogames: “They kill you over and over.” Something like that suspends you and makes you wonder just how long it took him to see those words in front of his mind’s eye. A Hemingway sentence makes you feel the same way. Each of Baker's paragraphs also seem to exist in a self-contained platform. You have to take a minute before you leap from one to the next, and isn’t that what paragraphs are supposed to do? And I’m not just talking about “One Summer,” where every one of the paragraphs starts with those two words. His short essays about “life” tell such stories as “How I Met My Wife” (not to be confused with How I Met Your Mother), “Why I Like the Telephone,” and “What Happened on April 29, 1994.” When you’re finished with them, you look up from the book and stare into the distance, with a silence that might alternately be called “a happy feeling.” He opens his last essay, “Mowing,” with: “Sometimes everything seems simple.” That’s deceptively true of Hemingway. And Baker.

Gone to the Forest: A Novelby Katie Kitamura

A ruthless, controlled style distinguishes this novel about a man and his oppressive father in an unnamed colonial country that’s about to blow—literally, in the form of a volcanic eruption.

Speaking of which, this is not a Hemingway parody: “Tom did not understand what was going on. Tom had not been on the veranda the previous night. He had been on the other side of the house.” It is the anchoring style of Kitamura’s new novel, a syntax that could drive one straight into the arms of Proust’s embraceable, full-bodied sentences. But lest you think there’s no meat here to squeeze, there certainly is a reason for these spare, repetition-strong, knife-edged lines. The novel, after all, is about Tom, an heir to a farm, who not only has to deal with his father’s oppressive authority but live under an unnamed colonial regime soon to dissolve itself and be relieved of its white settlers’ ownership. Kitamura’s obsession with control is a rather perfect evocation of such an atmosphere, and her style reminds one of Marguerite Duras and Herta Muller—writers who have had to reckon with power in the colonial Indochina and the repressive Romania, respectively. Power is the subject, and the execution is precise—even if this book will make you miss the comma terribly.

What in God’s Nameby Simon Rich

What would God sound like if he were a failing CEO? It’s not hard to see the current state of the world as evidence that Earth is a losing corporation, and a humor writer runs with the idea.

What are the most frightening words that might come from God’s mouth? “I don’t remember,” God said. “But don’t worry—I’ve got someone keeping track for me.” If God can’t even remember and He has to rely on someone else, it’s definitely time to worry. Simon Rich, one of the funniest writers in America, creates a God that’s Old Testament-y—He hardly gives a damn (sorry God) about shutting down Earth so that he can retire and open an Asian-fusion restaurant, which is a place that’s as good a metaphor for hell as I’ve ever seen. He (that’s Rich, not He) also has fun with God’s voice, having Him say things like, “Look, since we’re going into business together, I’m gonna level with you. With that whole mankind thing? I bit off way more than I could chew.” In a Miltonian move, Rich creates Craig and Eliza, two angels who bet God to call the whole thing off if they can get two earthlings, Sam and Laura of New York, to fall in love before doomsday. (When Laura picks Ace of Base on the jukebox, Sam loves it. “Craig clasped his scalp in horror. ‘I think Sam’s about to dance.’”) You know how this will end, but Rich evokes enough of the hellish qualities of Earth (Lynyrd Skynyrd, Walmart, a screenplay for Finnegans Wake) and of the little things that we’ll miss (Lynyrd Skynyrd, Walmart, a screenplay for Finnegans Wake) that it feels like a little love letter to the world. Thanks, life. Good of you to let me drop by.

Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the Worldby Simon Callow

A biography of Boz by a great English actor, who seeks to revise the standard argument that Dickens’s obsession with theatrical drama made his books sentimental and lachrymose.

Yes, Schikaneder from Amadeus and Gareth from Four Weddings and a Funeral can write, after tackling biographies of Oscar Wilde, Charles Laughton, and Orson Welles. This time he sets his sights on Dickens, and though he can’t hope to rival the effervescent storytelling and soul stirring of Claire Tomalin’s Charles Dickens: A Life, he can choose a unique angle and apply meticulous scholarship. Callow might look and play the buffoonish lush on screen, but he began on the great stage and continues to act and direct. So it is through Dickens’s associations with the theater that Callow has interpreted the greatest generator of immortal characters since Shakespeare. Dickens was an amateur actor, stage manager, and producer, and Tomalin is not the first to believe that this theatrical obsession contributed to melodrama and the lachrymosity in his novels—in other words, made them theatrical. But Callow argues that it is Dickens’s attention to stagecraft and the power of drama that’s made folks like the Artful Dodger and Miss Havisham seem three dimensional. Callow’s book is an important companion and counterweight to Tomalin.

The Dog Stars: A NovelBy Peter Heller

The travel writer Peter Heller introduces us to Hig, who must be the hunky fantasy of every romance reader—he’s a widower pilot who lives in an abandoned airport with his dog. A warmhearted novel follows.

Another novel with an overabundance of periods and a dismissive attitude toward commas. However, as Auden once warned, opening with such an obvious and shallow observation fails to acknowledge that the author may have foreseen exactly what I was going to say. And so I say that such deliberate quantum packaging of words is merely a shell that one has to crack to get to the warm heart of the novel. In fact, I can hardly think of a protagonist as engineered to be loved as Hig. (“Big Hig if you need another.”) Actually, more like seductive. He is a pilot who’s lost his wife and his family, and like a modern hunky Thoreau, has shut himself up and out of society’s view by occupying an abandoned airport, his dog, Jasper, by his side. I’m really not describing the front cover of a romance novel. Anyway, there is precedence to this, as Hig is not so different from the gamekeeper Mellors, who is Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Hig needs to open up, and when he does, guess what? The commas come a-returning. “Still, some nights I grieved. I grieved as much at what I knew must be the fleeting nature of my present happiness as any loss, any past.” It is a welcomed sight.