To say that I was the object of a Gore Vidal grudge is to place me in loftier company than I deserve. Norman Mailer, William Buckley, Robert Kennedy, Truman Capote, the entire United States government in all its incarnations for the better part of the last century—all these and many more were at the receiving end of The Great Gore’s scorn. Scorn was his stock in trade, and it is hard to think of anyone who wielded it with such energy and perseverance, or with such a glittering array of verbal weaponry.

My crime was relatively small. I wrote a profile of him for Vanity Fair some years ago, and in it I quoted his old friend Joanne Woodward, who told me she had acted as his beard. This, to Vidal, was infuriating because he maintained, in his eccentric way, that he was not homosexual in the first place—well, not exactly. He insisted that he was a homosexualist, that there was no such thing as homosexuality, that everyone is bisexual, and so forth. (Elsewhere on this website, Andrew Sullivan has brilliantly designated these convolutions as a “tic of his generation.”) The piece I wrote was respectful, but not worshipful, and that, too, was never good enough for Vidal. He had always felt himself to be improperly regarded as a penultimate, rather than the ultimate he so clearly was. A grudge was born, and revivified with the full force of his invective whenever my name was mentioned to him—which, blessedly, was not often.

Although he was one of the most familiar and celebrated figures of his era, Vidal always seemed convinced that he wasn’t held in sufficiently high regard. Did one know that, though uncredited, he was the true writer of Ben-Hur? Did one know about his connections to the Kennedys—not least that his mother later married Jackie Kennedy’s stepfather, Hugh Auchincloss? Did one know of his contributions to the Golden Age of television—he was an important early writer of teleplays—and of his friendships with Tennessee Williams, Marlon Brando, and Frank Sinatra? Was one fully aware of his noble birth?

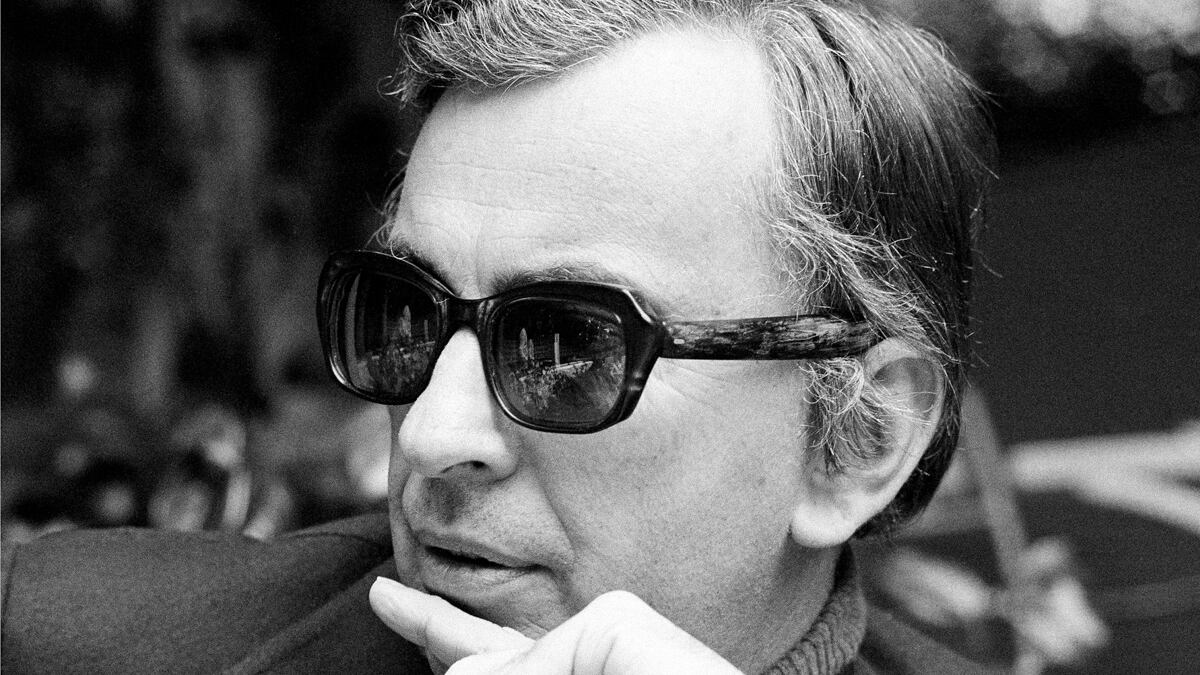

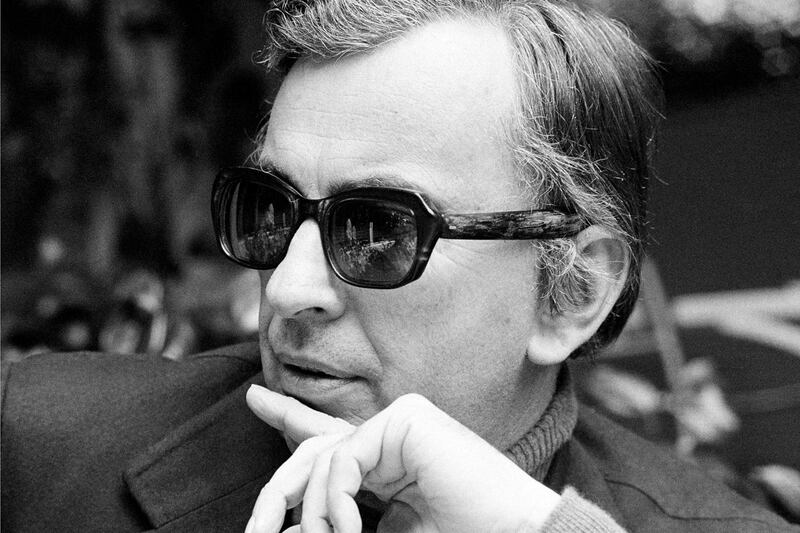

One was. Born at West Point into the American aristocracy—the grandson of a senator—Vidal was regally handsome and dazzlingly gifted. He could not but think that he was born to rule, but he soon came to see that he never would. Neither his sexual nor his political orientation would permit it—and, though he never entirely realized it, neither would his nature. With every cell of his being, he longed to outrage, to incite, to stir controversy, and from the moment he began writing and speaking, that’s exactly what he did. Although his most lasting contributions to fiction will prove to be his formidably accomplished but somewhat stiff historical novels—particularly Burr and Lincoln—Vidal’s earlier career as a novelist was dominated by path-breaking books that were often regarded as shocking, particularly The City and the Pillar (1948), a very prescient and frank study of homosexuality, and Myra Breckenridge (1968) a now almost forgotten comedy of transsexuality that caused a sensation in its moment and was later made into a noisome bomb of a movie starring Raquel Welch and, of all people, Rex Reed. Vidal would eventually run for office, twice, and was very proud of his showing as a Democratic candidate for Congress in a New York district, the 29th, that was a longtime bastion of Republicanism. Running as a Democrat at all in the 29th was typical of Vidal’s resolute perversity. He was an insider who insisted on being an outsider—and then on griping about it.

But oh, he was funny.

This has not been a good summer for the survival of the national wit. First Nora Ephron, now Vidal, two of the sharpest comic nibs America had seen in recent decades—though Vidal’s, unlike Ephron’s, was dipped in acid as much as ink. It is a commonplace to say that his essays were greater than his novels, and no one but Vidal himself could possibly think otherwise. But great those essays were—not just funny but gorgeously styled, stunning in their erudition, piercing in their invective. He seemed perpetually annoyed that we did not all see what he saw—the obviousness, to him, of American perfidy, of the folly of our global ambition, of the injustices to which those ambitions gave rise. And as he aged, that annoyance soured into a kind of world-weariness, as if he felt terribly taxed to be asked once again to don the heavy robes, to pontificate to the benighted about what was so blitheringly evident to him.

Vidal was born to be in the thick of the fray, and never could have been. But as a sniper from a very great height, he was incomparable.