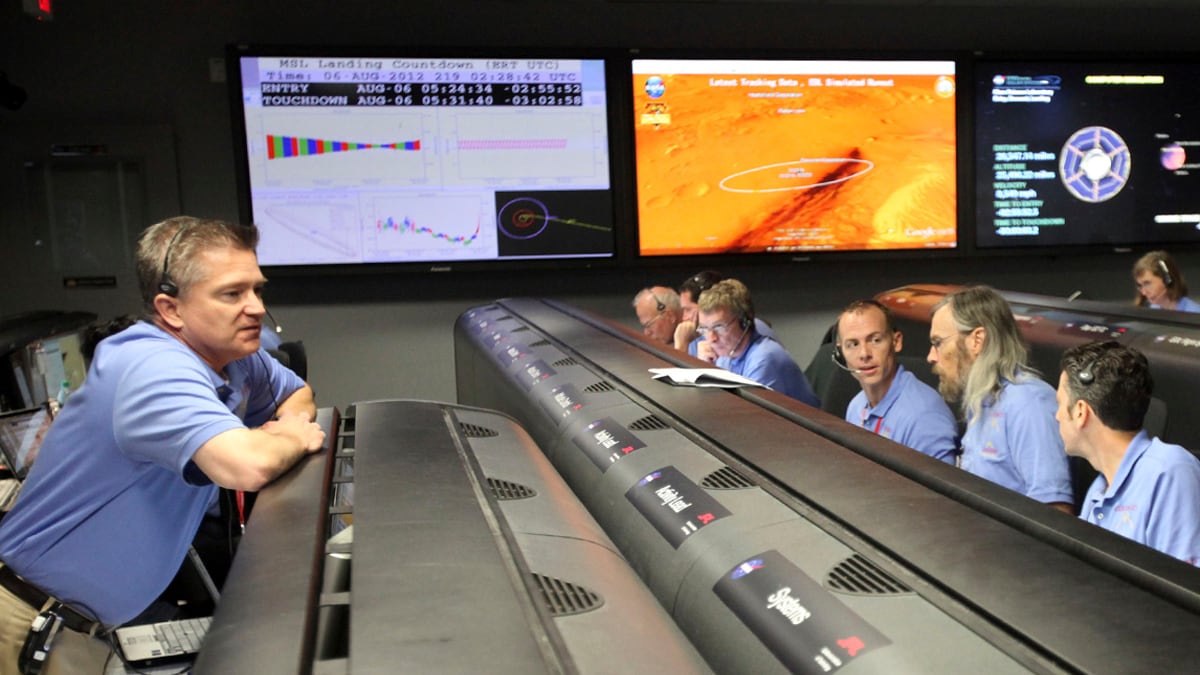

Sunday, August 5, 2012 Mission Control, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Pasadena, California

My minutes of terror begin far earlier than the last seven.

The first significant series of events that knots my stomach is cruise stage separation. Ten to 15 minutes before entry interface, during which the most significant electrical reconfiguration of the vehicle takes place, the pyrotechnic system is armed, the cruise hardware is turned off, the thermal batteries are ignited, the solar array is extinguished, the electrical and plumbing connections between stages are severed by guillotines, and finally, the separation of the cruise stage takes place. This intricate sequence wrapped us around the axle more than once during design and testing in the years preceding launch. Much of it is completed in the blind since cruise telemetry is turned off and Curiosity’s radio is switched from data to beeps. The radio transmission will even be turned off briefly during the main event.

Cruise Stage separation!! Beep! Curiosity is still there. Not good enough—is the cruise stage really gone?

Telecom reports the radio signal, once strong, faded and returned. The cruise stage slipped away and blocked the signal as it passed through the donut hole in the center and on beyond the circumference of the stage. The cruise stage is truly gone. Exhale.

No time to celebrate. Spin down, turn to entry attitude and jettison ballast mass in one minute. The capsule’s control jets will be used for the very first time. Will they work? Beep. Success! But are the ballast masses, so critical for the Apollo entry guidance to work properly, really gone as they should be? Won’t know until we attempt to steer the capsule through the Martian atmosphere in another seven minutes…when the Seven Minutes begin in earnest. Time to kill. Ugh.

The Martian gravity is pulling us in from about 11,000mph to a scorching 13,000mph. Entry interface coming up. Antenna switch. Heart-beat tones still there. “Beep.” Propulsion system pressurization. This event likely caused Mars Observer to go silent in the early '90s. Another dragon slayed. Navigation reports the Doppler signal is shifting…we’re feeling the atmosphere now. Guidance start. Here we go...

Beep! First bank reversal. Beep! Peak g’s: 10-12 earth g’s, within limits, the ballast masses are truly gone.

Ground Data Systems (GDS) reports processing Curiosity data relayed from the Odyssey spacecraft flying over our landing site. Beep! Second bank reversal complete. GDS interrupts: “Standby Flight. We have a connection but no data yet.” Is this going to work? Will we have to wait hours or days before receiving confirmation of touchdown? No worries. We’re prepared for this, but the moment won’t be as sweet.

“There we go.” Odyssey data is flowing! Heading alignment: Curiosity has completed guided entry. Slowing down in preparation for parachute deploy at Mach 1.7. Straighten up and fly right: the capsule is rolling and jettisoning its remaining ballast masses for parachute deploy. Parachute deploy! No. Not good enough... are we slowing down? Did Curiosity’s one parachute open successfully or rip to shreds as we’ve seen happen during development testing before we fixed it? Wait for the Doppler shift…YES!! The newly acquired rich Odyssey data confirms it: decelerating through 150 meters per second.

No time to rejoice. Up next: heat-shield separation and radar acquisition of the ground. Radar acquisition has always been a persnickety thing to test properly on Earth. It’s nearly impossible to test the hardware in the precise manner it will be used on Mars, much less in the proper flight configuration. We resorted to towered cable contraptions, helicopters, and even F-18 flights, in a patchwork attempt to cover the entire flight envelop. Did we get it right? And during integrated system testing, with Curiosity and all of its hardware resting quietly in a comfortable clean room at JPL, did we adequately represent the radar signals bouncing off of the ground to ensure the hardware and software work together properly on Mars? The struggle to get this right kept me in Florida when I wanted to be home for my wife’s birthday a year ago this week. Agonizing.

Watching for the radar beams to find the ground: one, two…three, four…five…six! The radar is working. Will the software recognize the data? Nav Filter converged!! Eight kilometers altitude! Oh, my God.

But wait: powered flight coming up next. Eight rocket engines that haven’t been fired since 2007 must all work or the mission is over. Just one stuck throttle means disaster. Ninety meters per second, 6.5 kilometers…still high…waiting… “TWTA warnings…” Not to worry. Fault-protection software has been programmed to ignore that—powering through it. Eighty-six meters per second, four kilometers. Waiting for parachute separation…

“We are in powered flight!” Events start happening really fast now. Thirty seconds to landing. One kilometer, 70 meters per second. The engines are working! Fifty meters per second, 500 meters. Standing by for Sky Crane…I thought this was crazy six years ago when I first joined JPL. Is this really happening? Ten meters per second, 40 meters above the ground.

“Sky Crane has started!” Descending at 0.75 meters per second, less than two miles an hour. Spot on. Telecom reports: “Signal to Odyssey remains strong.” Our final radio reconfiguration was successful! In our final two landing rehearsals, we didn’t see telemetry beyond this point. Are we really going to see this thing all the way to the ground!?

“TANGO DELTA NOMINAL!” “RIMU stable.” “UHF is good.” Curiosity is on the ground and not moving. The landing speeds were gentle. Curiosity is still talking to us. But the descent stage is still hovering above her. Guillotines must cut the cables and electrical cord in the right sequence to begin Fly Away—or it’s game over. Wait for it…

“TOUCHDOWN CONFIRMED!!”

I thought I knew how I was going to handle myself after touchdown—had a plan and everything. Forgot about it. Six years of hard work, long hours, incredible stress. A two-year slip in 2009 when we recognized we couldn’t make the launch window that year. Innumerable problems identified, diagnosed, and solved. A five-month launch campaign in Florida at the Kennedy Space Center away from my family.

Words fail me.

I can’t wait to see where our Curiosity takes us.