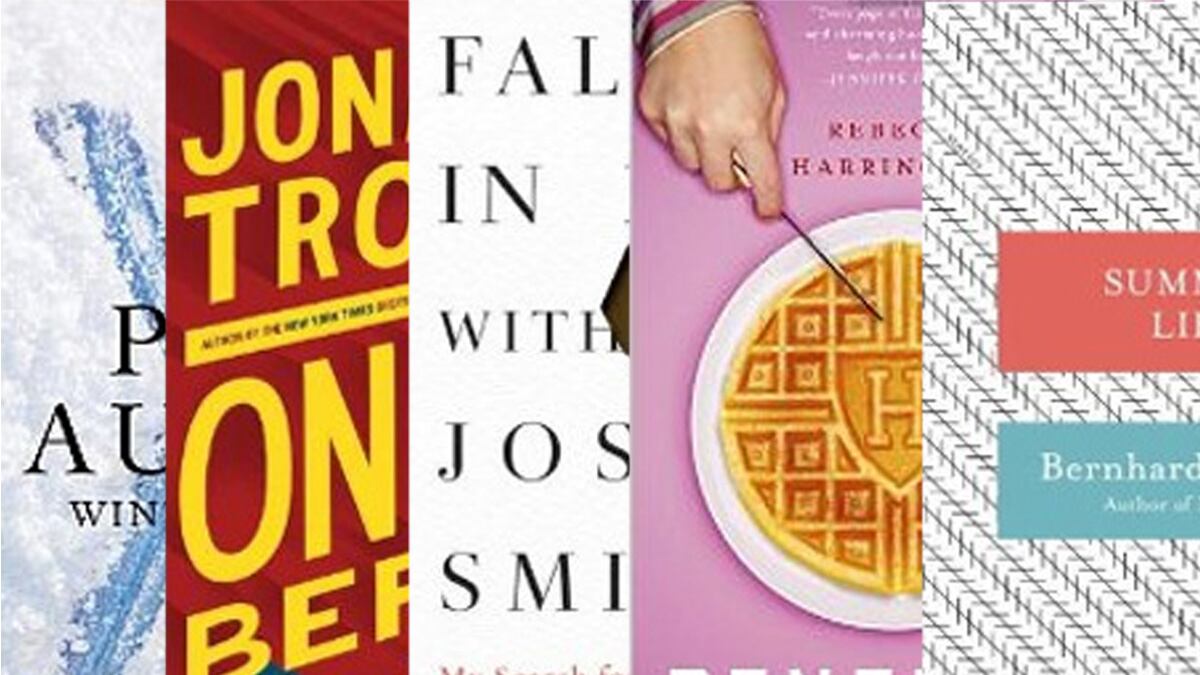

Winter Journal By Paul Auster An acclaimed writer looks back on his memories of two marriages, two children, and 21 permanent addresses.

Second-person narration has a way of being both accusatory and evasive; in Paul Auster’s elegant new memoir, it’s arresting, too, underscoring the strangeness of watching oneself age. Painstakingly cataloging two marriages, two children, and 21 permanent addresses, Auster carries the reader from his youngest memories as a boy who loved baseball and his dog through thwarted high-school passions, college protests, marriage, parenthood, divorce, love and loss.

Though this is an extraordinarily intimate book, readers familiar with Auster’s life and career will notice a few large omissions. While he writes tenderly and at length about his love for his wife and the loss of his mother, Auster’s children never emerge as individuals. There is no mention of the burgeoning stage and music career of his daughter Sophie, a 20-something Manhattan “it” girl, or of his son Daniel’s 1998 guilty plea to stealing $3,000 from a deceased drug dealer (an event fictionalized in What I Loved, the novel by Siri Hustvedt, Paul Auster’s wife). However, Auster doesn’t owe his readers reflections on these parts of his life. A memoir is ultimately personal accounting as much as public reckoning.

Now 65, Paul Auster is no longer a young man. But he is not yet an old man either. As such, perhaps he’s not entirely ready for a complete reckoning. The proliferation of “you” and an absence of “I” hint at the emotional challenges of memoir writing. Describing, for example, the car accident that could have killed his wife and daughter, Auster notes sternly: “You took a chance you shouldn’t have, and that error of judgment continues to fill you with shame.” Auster may be lecturing himself, but it sounds oddly like he’s addressing someone else entirely.

Summer Lies By Bernhard Schlink Late-life love, with its attendant vulnerability and disappointment, comes into focus in a new collection of short stories from the author of ‘The Reader.’

Nearly all of the characters in Summer Lies, German writer Bernhard Schlink’s new collection of stories, find themselves at a crossroads. Some of the collection’s sharpest stories look at the love between a man and a woman, but there are heart-rending tales about the gaps between a father and son (“Johann Sebastian Bach on Reugen”) and the tenuous bond between a grandmother and her granddaughter (“The Journey to South”). Late-life love, with its attendant vulnerability and disappointment, features prominently in this collection. So does death.

“He was happy—or did he just want to be happy because everything was going well? Because all the components of happiness were there.” This is the question that haunts the protagonist of “The Last Summer,” a grandfather dying of cancer. Sensing his end is near, he has planned a final happy summer for himself surrounded by family and friends at his lake home. He has planned his death, too. When the pain is too strong, he’ll drink a suicide cocktail and quietly go to sleep. But things don’t go quite as planned. His wife discovers the cocktail, and feeling betrayed by his death wish, leaves him, taking his children and grandchildren with her. He ends his summer at the lake house deeply alone. “Once again he had had all the components at hand, but happiness had not resulted,” he realizes. And yet, “This was different from the times before; he had been truly happy for a while. But the happiness hadn’t wished to remain.” Such are the anguished lessons of this beautiful, bittersweet meditation on the strains of ordinary love.

Falling in Love With Joseph Smith By Jane Barnes A PBS documentarian assigned to work on a film about Mormonism falls for its prophet.

For some spiritual seekers, the prospect of complete personal transformation—a rebirth, a reeducation, a reinvention—is even more seductive than any promise of salvation. This seems to be the case for Jane Barnes, a WASPy middle-aged divorcée and documentarian who, while working on a PBS film about Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, finds herself falling head over heels for her research subject. “I love everything scandalously starting afresh, all connected and confused,” she writes. And what could be more freshly scandalous than an East Coast liberal embarking on a serious flirtation with Mormonism? Barnes’s fascination with Smith sends her on a religious and genealogical journey: she reads The Book of Mormon cover to cover, daydreams about the inner life of the young prophet, unearths distant Mormon forefathers on her family tree, and starts becoming convinced that Mormonism is her destiny. Primed for a conversion, she meets with church elders and even attends services. (“It was like an NPR program: the people’s voice was heard,” she notes.) But despite her careening passion, she is unable, finally, to make the leap from groupie to devotee. Idiosyncratic and unfocused, Barnes’s account is part prattling confessional, part foggy revisionist historiography. Her frequent digressions are more tedious than illustrative. At one point, she details the lesbian affair that ended her marriage; at another point, she writes Joseph Smith into a fictional, Mark Twain–style episode featuring Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. But for all its self-indulgence, there is an admirable curiosity at the book’s core. To call it a love story, though, seems an overstatement; in the end, it’s never clear that Barnes’s preoccupation with Mormonism is more than a timely infatuation.

One Last Thing Before I Go By Jonathan Tropper The diagnosis of a fatal heart condition leads a washed-up rock star to reevaluate his life with a measure of dark humor in this novel.

What’s the difference between suicide and capitulation? Drew Silver, who’s known simply as Silver, isn’t sure, but he is pretty sure he doesn’t have much to live for. He’s lonely and out of shape and lives in a dingy apartment full of other sad men like him called the Versailles. Now that his band and marriage are broken up, Silver gets by as a wedding musician, supplying sperm to medical studies for extra cash. He has no illusions: his is a pathetic existence. So when he’s diagnosed with a potentially fatal heart condition, he’s not exactly in a hurry to get the life-saving surgery prescribed. It’s not just that the surgeon is his ex-wife’s fiancé. It’s that Silver knows he’s failed miserably at being a husband, a father, a rock star, and, let’s face, it, a man. He’s not sure he wants (or deserves) to extend his lease on life.

If anyone could make him reconsider, it’s Casey, his wry, beautiful Princeton-bound teenage daughter, who happens to be in midst of a crisis of her own: she’s pregnant. Silver needs Casey and Casey needs Silver. But as it happens, she’s not the only one. Silver’s father, mother, brother, ex-wife, and sad-sack friends want him in their lives, too, but it takes Silver a lot of bumbling and soul-searching to understand why. Yes, this is a made-for-Hollywood dramedy (in May, Paramount closed a seven-figure deal for screen rights to the novel), but it’s hardly canned. Tropper’s characters are likably zany and fallible, and perhaps more important, funny. One Last Thing Before I Go is a poignant story about facing death and celebrating life, even when things seem well beyond repair.

Penelope By Rebecca Harrington A Harvard freshman seeks friendship among overprivileged climbers, antisocial geniuses, hyperambitious strivers, and hopeless geeks

To be misunderstood in high school is to be granted entry to an important sphere of American lore—to join ranks with the likes of S. E. Hinton and John Hughes characters. But what if there’s no post-high-school redemption? What if the awkwardness of high school is only amplified in college? This is the particular predicament addressed in Penelope, 26-year-old Rebecca Harrington’s debut novel. Harrington’s title character is an incoming Harvard freshman anxious about making friends. Her concerns, it turns out, are well founded. The nerds of Penelope’s high school were “small damp spirits” who busied themselves with Sim City and glue guns; “These Harvard people,” on the other hand, are “different types altogether.”

In Harrington’s telling, Harvard’s confluence of overprivileged climbers, antisocial geniuses, hyperambitious strivers, and hopeless geeks results in a special breed of dysfunction. It also makes for absurdly off-kilter dialogue. But things could be worse. Penelope apparently has the kind of face drunken boys are inclined to suddenly plant their lips upon. (A hall mate compares her to Helen of Troy.) As Penelope flits from one awkward interaction (and makeout session) to another, hilarity ensues, culminating with her most significant accomplishment of freshman year: winding up on stage in an avant-garde production of Caligula.

To Harrington’s credit, this is a book that doesn’t take itself too seriously. Penelope is closer in sensibility to an anodyne sitcom than a precocious bildungsroman. There are no wrenching epiphanies, just mild embarrassments and a surfeit of confusion. As the novel’s characters anxiously chatter about Lloyd Blankfein, Thomas Pynchon, the Harvard-Yale game, and housing arrangements, Harrington invites their mockery. In Penelope’s depiction of Ivy League, the stakes may be low, but the comedic payoff is high.