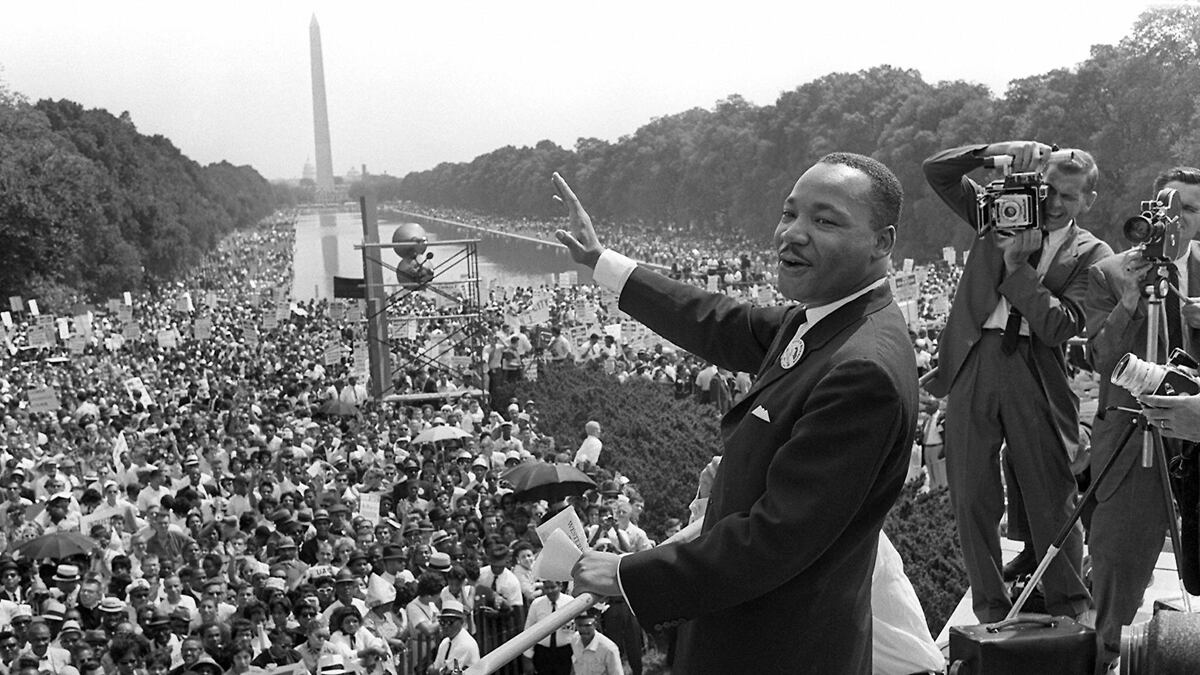

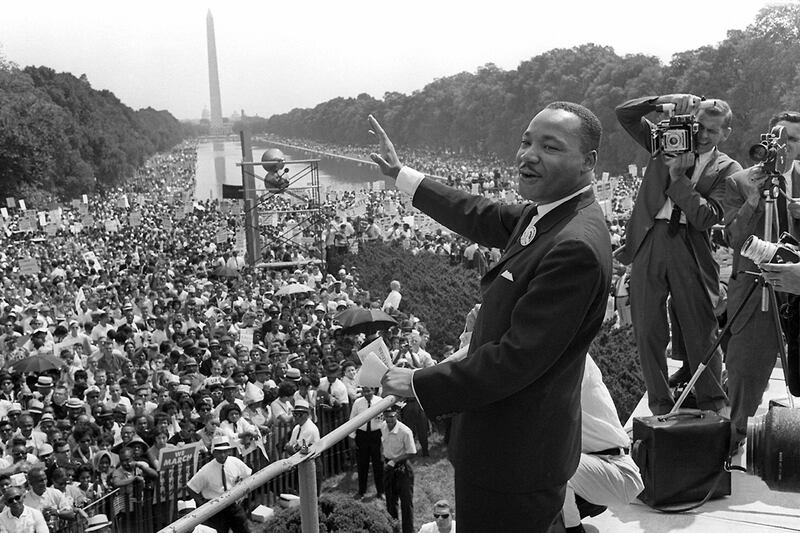

Fresh from the police dogs, the bombings, and “We Shall Overcome” marches in Birmingham, I remember the buses rolling into Washington from New York, New England and the Midwest in the pink dawn of August 28, 1963, and the people expectantly making their way toward the Lincoln Memorial.

The Freedom Riders and civil-rights marchers from battlegrounds across the Old Confederacy came mostly by car, a few by train—the young people, black and white, who had braved nightsticks, fire hoses, and angry white mobs, now joined by the doctors, lawyers, and small-business owners who had put up bail to get the protesters out of jail, and the professors, ministers, and other Americans from around the country who supported their cause.

Washington’s city fathers were braced for the worst. They feared an emotional crowd worked into a volatile fever by their leaders or stampeded into a rampage by racists bent on fomenting trouble.

But the crowd was peaceful, calm, and dignified. It was a huge, polite middle- class throng, mostly blacks but many whites too. “No one could remember an invading army quite as gentle as the 200,000 civil rights marchers who occupied Washington today,” my colleague Russell Baker wrote in The New York Times.

Thinking of the violence and tensions I had witnessed as a reporter covering the struggle in the Deep South, I was struck by the relaxed and cheerful mood of that citizen army. Parents played with children or lolled under the trees by the Reflecting Pool. Others sauntered toward the Mall or spread blankets beneath the rising sun, fathers dozing off with newspapers folded over their eyes. The event had the sunny air of a mass picnic.

But this was no picnic. It was history in the making, the largest peaceful demonstration that Washington had witnessed until that time. It was more than that, too. It was a festival of democracy—a mass celebration of the power of civic activism, of insistent pressures from the heartland for elected officials to respond to popular demands for fairness, equality, and social justice.

There is a lesson for us today in that scene—a lesson not just from the March on Washington but from other populist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. These were important manifestations of people power—of the political power of average Americans to shape public policy and to make government work for ordinary citizens, and not just for the financial elite and the political establishment.

Unlike most Americans today, who feel ignored by the powers-that-be in Washington and powerless to alter that situation, millions of ordinary Americans in the 1960s and 1970s believed in their own political might. They believed that by acting together they could influence the nation’s agenda and affect government policy.

In those days, average Americans felt confident that they counted politically. They acted on that confidence and they generated a period of unprecedented citizen activism and political and economic reforms from the 1950s into the 1970s, the heyday of the American middle class.

Middle-class Americans fought for change—and they won change—through the demands of the civil-rights movement and the women’s movement for equal rights; through the environmental movement and its fight for clean air and water; through the push of the consumer movement for a better quality of life and more honesty in the marketplace; through the battle of the trade-union movement for a solid middle-class standard of living and a secure retirement; and through the peace movement and its mass protests to end the war in Vietnam.

The March on Washington and the civil rights protests that preceded and followed it helped to turn Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream into law—for a balky Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, desegregating public facilities, and then to enact the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The consumer movement, spearheaded by Ralph Nader and his attack on the auto industry for producing defective cars that caused traffic fatalities, generated a slew of legislation promoting the safety of consumer products and truth in packaging and lending that still benefit us today.

Hard to believe now, but on Earth Day 1970, roughly 20 million Americans, close to 10 percent of the nation’s population, participated in demonstrations across the nation, and there followed a flood of environmental legislation—the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and many more.

As Williams Ruckelshaus, the first head of the Environmental Protection Agency, admitted to me, those protests turned around a president—Richard Nixon. The explosion of public anger, Ruckelshaus said, “forced a Republican administration and a president who had never thought about [the environment] very much—it forced him to deal with it because the public said: ‘This is intolerable. We’ve got to do something about it.’” And so Nixon, who counted himself a friend of business and a fan of CEOs, established the EPA and a host of other regulatory agencies and commissions to curb the excesses of business.

In short, average Americans saw ample evidence of their own political muscle. American democracy was healthy and vibrant.

Not so today. Most Americans feel powerless. They have become disenchanted and politically disengaged and, as a consequence, effectively disenfranchised. In the telling insight of populist organizer Ernie Cortes, not only does power corrupt, but “powerlessness also corrupts.” It drains the lifeblood out of democracy and corrodes the animating idealism of the body politic.

The Tea Party activists, the “Occupy” protesters, and a developing movement to “Take Back the American Dream” understand this. But the vast majority of us have largely lost our civic faith, our faith in ourselves, our faith in the ability of average people, when organized, to counter the force of the organized political money of Wall Street, corporate America, and the super-rich.

If there is widespread discontent among the American middle class, as there is, then it’s time to take inspiration from the March on Washington, It is time for a peaceful middle-class rebellion. To confront and combat the influence of money in the New Power Game that now dominates Washington and our national politics, average Americans must exercise their unique political leverage—direct personal engagement in movements for middle-class causes.

“Americans have reason for negative attitudes,” the late John Gardner, head of the public-advocacy group Common Cause, observed several years ago. “But the sad, hard truth is that at this juncture the American people themselves are part of the problem. Cynicism, alienation, and disaffection will not move us forward. We have major tasks ahead.”

The challenge reaches beyond the next election. Voting is essential, but voting is not enough. Taking action and staying engaged on the most vital issues after elections is essential. Otherwise, armies of well-paid lobbyists will override the election results and keep on tilting our laws in favor of the economic oligarchy that now reigns in Washington, whichever party is nominally in control.

To break the political gridlock on a much-needed middle-class agenda, what’s needed is a civic-action campaign, with legions of ordinary people participating in the battle, first and foremost, for jobs, homes, taxes, and fairness: a more level economic playing field; a fairer tax code; laws requiring Wall Street’s bailed-out banks to refinance home mortgages at today’s lower interest rates, helping millions of people to keep their homes and lifting the economic drag of a dead housing market; an immediate and sustained drive to revitalize America’s worn-out infrastructure that will generate millions of jobs and make America more globally competitive again. The agenda goes on.

The missing ingredient is an American political spring. If Arabs can march in the streets of Tunis, Cairo, and Tripoli, topple dictators and generate their “Arab Spring,” and if Israel’s populist street movement can compel a conservative government to adopt economic reforms, then why not a political spring in America?

If we genuinely want government of the people, by the people, for the people, instead of government of the super PACs, by the super PACs, for the super PACs, then millions of average Americans must get—and stay—personally involved once again in direct citizen action. The only reliable countervailing power to organized money is organized people.

Regardless of who wins the election, We the People must make our voices heard and our power felt in the halls of government—just as millions did in the 1960 and 1970s—to restore the vital link between Washington and the people.

Think for one more moment about that day 49 years ago. Picture that energized and expectant crowd in the March on Washington at the feet of Lincoln. Hear the soaring anguished cadences of Martin Luther King Jr. proclaiming an American Dream. And remember that now, as then, politicians will listen to middle-class America once it marshals its forces.