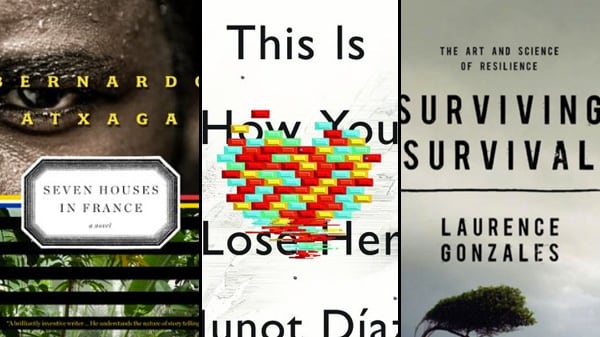

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz The Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist releases a new collection of short stories.

“I’m not a bad guy,” the first story in Díaz’s collection begins. Is it an apology or an introduction? Yes, he is “a sucio, an asshole.” But no one loves women more than he does, their “big stupid lips,” “horse neck,” “sad moonface” features, “curried pussy,” and all. Infidelities end at least a third of the relationships in this book—this is a songbook of eulogies to love affairs that never stood a chance in the first place. Sometimes class, race, or age is to blame, sometimes fate, time, or sheer stupidity. Sometimes, the weather. Many of these stories will be familiar to New Yorker readers; nearly all have appeared in the magazine in the past decade and a half. As individual works, their spiky, expletive-laden language and misogynistic gestures seem engineered to provoke and estrange. Taken together, their braggadocio softens into something much more vulnerable and devastating. The intimacy and immediacy of these stories is not just seductive but downright conspiratorial. Still, returning to the genre rather than releasing another novel seems to be a source of embarrassment; in a recent interview, he likened it to “giving birth to girls in a Dominican conservative family in the '50s.” If that’s the case, Díaz’s little girl is a heartbreaker.

Surviving Survival by Laurence Gonzales What makes some people more resilient than others?

Sharks, crocodiles, bears, and abusive husbands are just a few of the uncontrollable predators whose victims Laurence Gonzales interviews in this follow-up to his book Deep Survival. Here it’s not survival itself but the mental fortitude and emotional resilience necessary for long-term recovery that drives Gonzales’s narrative. Each story of a near-death encounter becomes a case study in how successful survivors develop and deploy the resources necessary to move past their trauma and reestablish something like normalcy. At 24, while on a hike with her husband, Patricia van Tighem was attacked by a bear. The bear took the skin on her face and her left eye, cheekbones and eyelids. For her story and others, the book relies heavily on anecdotes backed with stripped-down brain science (for example, “Stress dumps special chemicals into your bloodstream”) to give order to violent and tragic experiences. In Patricia’s case, after dozens of surgeries and extensive therapy, she went on to have four children and to write a bestseller (The Bear’s Embrace) about her experiences, making television appearances on the BBC and National Geographic Channel. Gonzales resists the temptation to tell only stories about flourishing survivors. “That would seem to say that some of us are good and some of us are not deserving. That if you just set your mouth right, you can plunge ahead,” he writes. Twenty-two years after her attack, Patricia ended her life. In the end, there are no clear answers on who manages to reemerge whole—just rich stories that offer flashes of insight into what it means to live on.

Seven Houses in France by Bernardo Atxaga Greed breeds destruction in the Belgian Congo.

When it comes to tales of corruption in the Belgian Congo, it’s hard to compete with the canonical squalor of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But Seven Houses in France manages to infuse a colorful layer of vulgarity and humor into a familiar portrait of abuse. Drinking, gambling, raping native girls, and shooting monkeys for sport are just some of the pastimes of the men representing the ship Leopold II at the Congolese outpost of Yangambi. Captain Biran, Leopold’s first in command, has a few additional personal pastimes to add to the list: writing poetry, shooting elephants, and sending tree trunks up the river. Though Yangambi has been bad for the captain’s literary output, it’s done wonders for his bank account. The book’s title refers to the houses Captain Biran has been able to purchase for his wife—one for each year he spent in Africa—with money from the mahogany and ivory he stealthily ships out of the jungle. The arrival of an oddly disciplined soldier named Chrysostome, however, changes the tenor of the life in Yangambi. Chyrsostome’s chaste habits and perfect marksmanship make him an object of both scorn and envy among his more rakish compatriots—in particular, the heavy-drinking hot-headed Van Thiegel. It doesn’t take long for tensions to spiral out of control, plunging the camp into chaos. Captain Biran’s final words are a bit more measured than Mr. Kurtz’s, but no less haunting: “I am going to the eighth house.” A French journalist reporting on the death glibly explains that in Kabbalah the eighth house is the house of death; no one disputes him.

The People of Forever Are Not Afraid by Shani Boianjiu Three teenage girls leave their small village to serve in the Israeli army.

The much-anticipated debut novel from 25-year-old Shani Boianjiu zigzags between the stories of three high-school friends, Yael, Avishag, and Lea, as they leave their small village on the Lebanese border to take up posts in the Israeli army. Yael teaches marksmanship, chases boys, and spins dirty stories for her friends. Lea, a checkpoint guard, witnesses another soldier’s neck get sliced by an angry Palestinian. Avishag, stationed at the Egyptian border, gets pregnant by her supervising officer—she goes to the clinic for an abortion after having lunch at McDonald’s with him, and returns directly to duty. Though their stories and personalities are distinct, the young women’s voices—angry, funny, haunted, and raw—are nearly indistinguishable. This blunts the force of their individuality, though it heightens the impact of their collective damage. Lea makes up stories about the people she sees at the checkpoint each day; Yael fantasizes about the young male soldiers she works with; Avishag occupies her mind with imaginary miniature people in the pixels of her computer screen. Together, they hover on the edge of reality, dangerously poised somewhere between girlhood and womanhood. For every cigarette, there is a lollipop, and for every act of violence or despair, there is a moment of sheer comic absurdity. These glimmers of humor and insight flash brightly in what is a brutally dark novel: “I know we were just girls. We did what we did in the army, and then it was over ... the problem was the future of the past. It existed outside our heads, too large.” Hidden America by Jeanne Marie Laskas A journalist visits coal mines, air-traffic-control towers, and blueberry fields to understand the lives of America’s unsung heroes.

How do air-traffic controllers remember what instructions they’ve given each flight? How do cattle ranchers produce a signature steak? Who picks the blueberries sold stacked in neat cartons at the grocery store? “We don’t pal around with them on our college campuses and they are not invited to be pundits on TV,” journalist Jeanne Marie Laskas writes in Hidden America. Laskas sets out to uncover the men and women whose largely unseen work animates ordinary life. It’s a noble premise pursued with gusto. But for a veteran reporter, Laskas at times displays a strange naiveté about the workings of the world. Making inquiries at a gun store in Arizona, she’s surprised the store’s patrons are vocal supporters of the right to bear arms (“I hadn’t come to Yuma to discuss the Second Amendment, but it kept coming up”). At one point she muses that “it is difficult to understand why so many beautiful young women would eagerly and longingly” choose to be professional cheerleaders. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, in her telling, exists because of “lawbreakers and people in countries without regulations” rather than the simple over-consumption of law-abiding Americans. Nevertheless, the candor and charm of her wide-eyed approach has a way of opening up her subjects. She meets a philosophizing coal miner trying to be a better father and heartbroken 30-something woman truck driver wondering if she’ll ever have a family of her own. “Sometimes I just think my give-a-shit spring is about to bust,” an Alaska oil-rig operator confides. Hearing their voices, it’s impossible not to see the world a little differently.