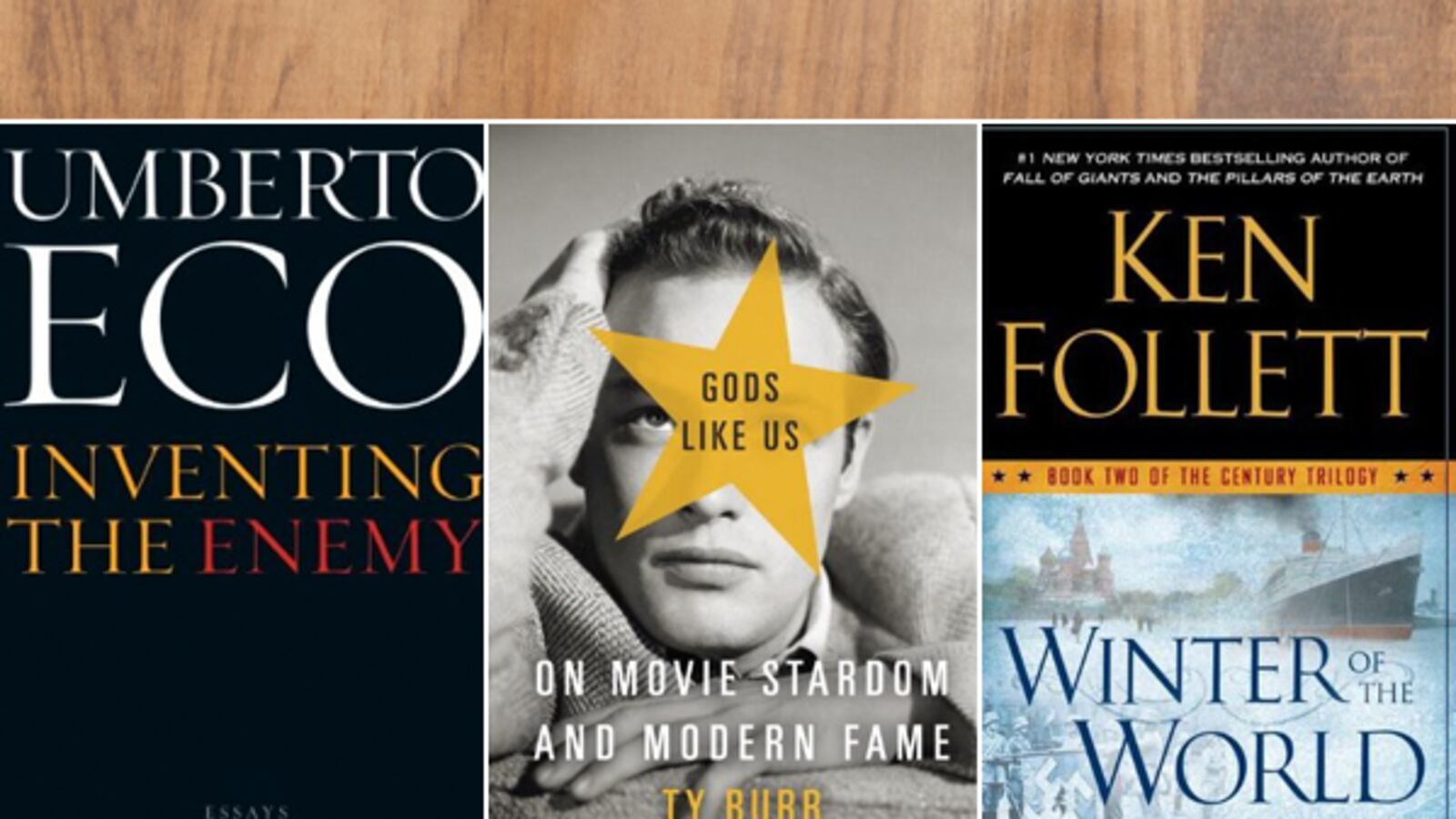

Gods Like Us By Ty Burr

Writing about performance and stardom well is the most difficult thing in film criticism—hats off to the Boston Globe film critic for a necessary history.

Film criticism has traditionally centered on the director. The artistic vision comes from the auteur, and at his or her disposal are things like mise-en-scène, montage, screenplay, and actors. A movie star’s talent is one element used to create a work of art, like paint in a Monet or words and sentences in a Flaubert. The problem is that stars are not objects. What an actor provides—gestures, movement, speech, a smile, a gait, a wink—is inseparable from who he or she is, which makes performance the most difficult aspect of film to write about. To extract an actor’s contributions requires psychobiography of extraordinary complexity, and so we, the public, create an entire category of existence for them: the movie star. Early in the book, Burr, the film critic for The Boston Globe, writes about crossing paths with Robin Williams. “A very small moment of human connection between two people had been squelched by the appearance of a third, not-quite-real person: the movie star.” We manipulate “the movie star” at will, oblivious to the effects on the person behind the persona. Actors, fans, advertisers, the business of film, and the sign of the times all have a hand in building stardom, and it is the critic’s duty to peel apart the myth. The classic text is Parker Tyler’s “The Awful Fate of the Sex Goddess,” in which he psychoanalyzes not so much Sophia Loren or Greta Garbo, but the very construct of a sex goddess. Then there is David Thomson’s monumental The Biographical Dictionary of Film. Today, it is theater critics like The New Yorker’s Hilton Als who make it their mission to give performance and persona their deserved attention. Burr’s Gods Like Us is a constantly interpretive history of and idiosyncratic meditation on stardom, from Florence Lawrence to Heath Ledger. It is an important work, precisely because it is such a difficult task that is all too rarely undertaken.

Inventing the Enemy By Umberto Eco

A collection of essays that even the author, in the introduction, admits should be called ‘Occasional Writings,’ on topics he had no special interest in.

How will Umberto Eco be remembered? As a novelist he is a pusher of recondite pleasures. Only Foucault’s Pendulum registers anything like full-bodied relevance, and then only because it invented Dan Brown and anticipated that people’s brains would turn to mush reading the junk stupidity of The Da Vinci Code conspiracy theories 15 years before they existed. His academic semiotic and philosophical works wield a thousandth of the influence of his bestsellers. The same problem applies to his fellow language guru Noam Chomsky, yet Chomsky at least justifies his politics and activism through the importance of linguistic and scientific clarity. Eco does not put enough thought into how readers engage with his fiction, and in so doing his postmodernism is far less postmodern, simply a shell. The champion of “the open work” nevertheless creates worlds that are rather closed. Eco’s new collection of lectures and essays demonstrates a similar feebleness, though it is as readable as a bestselling writer ought to be. And in talking about “Imaginary Astronomies” and geographies Eco shows what he’s best at: drawing gorgeous Ecocentric worlds. But what you get out of the title essay is that countries must invent an enemy even if they really don’t have one. But exactly how much more profound is that than saying simply that humans are sometimes aggressive and competitive? He is best when introducing general readers to less-known writers like his fellow Italian Piero Camporesi, or to obscure texts, often Latin ones. Mentions of Saint Alphonsus de Liguori or Ercole Mattioli produce a spark or two, but “The Beauty of the Flame,” a survey of exactly what the title suggests, would have benefited from just one resplendent description of fire—a novelist’s description, like D.H. Lawrence’s “that rushing bouquet of new flames” or Norman Rush’s “cooking fires wagged.” Alas, for all those novels he’s sold, perhaps Eco is not really a novelist after all, but a dealer in handsome esoteria.

San Miguel By T.C. Boyle

It’s no wonder old-fashioned realist craftsmen like Boyle love islands. This novel is set on a windy Californian rock, and the isolation brings out the stormy complexity of the three female protagonists’ minds.

Speaking of D.H. Lawrence, T.C. Boyle, another ye of the double abbreviation, might be the man who writes most like him today. “All the talk was of the shearers—the shearers were coming, the shearers—until she began to think they were some messianic tribe bent on redeeming them all.” The repetition is very like Lawrence, though of course the triple “shearers” mimic the constant talk and their shamanistic quality. Or, this is how the book begins: “She was coughing, always coughing, and sometimes she coughed up blood.” Coughing, of course, happens in threes, fours, more—not to mention always coughing. The cougher is Marantha, who goes to the island of San Miguel off the coast of southern California in 1888 with her husband. (Boyle lives in the state, and his previous book, When the Killing’s Done, is set on the Channel Islands.) There’s also her daughter, Edith, who dreams the quintessential California dream of being an actress, though film and Hollywood didn’t exist yet. The last part of the triptych brings us to 1930 and features Elise, a New York librarian who only knew of the West from books by Francis Parkman, Mark Twain, and Willa Cather, until she, too, settles on the windy rock. Will she repeat the mistakes of Marantha and Edith, and how did these corset-wearing women survive the natural desolation of San Miguel anyway? Boyle’s devotion to the inner lives of his characters shows that their minds were rich weapons against the forces of nature and history.

Between Heaven and Here By Susan Straight

The last of the Rio Seco trilogy, though the events—the death, burial, and investigation of hooker and junkie Glorette—happens in between the previous two installments.

Straight’s new book is also Californian, but located in the fictional town of Rio Seco, where she sets almost all her stories. (The town is based on Riverside, where she lives.) A Million Nightingale, even though it is the first in what’s referred to as the Rio Seco trilogy, is set in Louisiana. It features the ancestors of the characters in 2010’s Take One Candle Light a Room, though the events in that book actually happen after this final installment. Straight, a 2001 National Book Award finalist for Highwire Moon, has the ability to create straightforward contemporary voices, no pun intended. She does not subscribe to the maximalist school of over-the-top characters, yet she can still dramatize the complex, jagged nature of American culture today. Her greatest creation in this book is the prostitute and junkie Glorette Picard, whose burial preparation and death investigation span the entire novel—her wraith-like occupancy is on every page, with every character. The plot could fit in an episode of CSI, but a sharp and glancing line like “Why have buttocks? What good are they? And hair?” hardly seems to belong but pops up everywhere. It shows a writer who takes her time, even revels in it—in the past, present, and future. She reaches across the years, back to A Million Nightingale and onward to Take One Candle Light a Room. How is it that Between Heaven and Here is only about 200 pages? It is a very rich 200 pages.

Winter of the World by Ken Follett

An impossibly large ‘History of the World, Part II’ in novel form, without the preview of coming attractions, and without Mel Brooks.

Winter of the World is not 200 pages. It is nearly a thousand. And while Straight has the courtesy to wrap up her three-parter, Follett’s only on book two, which only gets us as far as August 29, 1949. Since the first book, Fall of Giants, started on June 22, 1911, and Follett has threatened to deliver “The Century Trilogy,” will the next installment be tall enough to use as a bar stool? How else to get us to June 22, 2011 and fulfill his campaign promise? Follett’s historical epic follows five families: American, English, Welsh, Russian, and German. Since his interest seems to be trying to fit in as many relevant world developments as possible, the Chinese, French, Indian, Arabian, Egyptian and Argentine delegates are planning to protest through the U.N. General Assembly. Much of what goes on in the world are touched upon by banter during walks to the store or over dinner tables, like, “How is the soup?” as Katerina asked Zoya, and they go on to talk about Hitler. But after a few more years of soup Zoya would also help build the first nuclear bomb. What drove so many people to retake World History 101 through a thousand pages, as they did in Fall of Giants, and will they follow Follett down the path again? Of course they will. We human beings love the familiar. We flock to the History Channel for narrations about good Allies versus evil Fascists, for a chance to feel that we are standing on the side of the good guys, against the perpetrators of the Shoah. The tick-tock of the story will not change. The certainty is very satisfying. Book three will have to contend with postmodern times—the end of history, and the birth of a greyer, flatter world.