The op-ed pages of major newspapers are littered with the bylines of formerly great journalists. Too often the sinecure of punditry causes writers to become enervated in their thinking, lazy in their prose. Tom Friedman—now a frequent subject of parody for his repeated quoting of foreign taxi drivers, his muddled metaphors, his bizarre neologisms—is a prime example of a once fine foreign correspondent gone to seed.

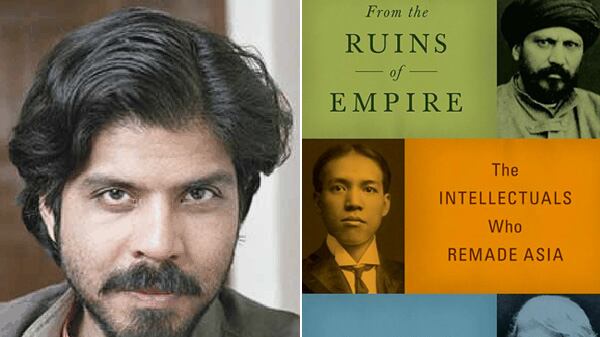

For that reason, I've had mixed feelings observing the rise of Pankaj Mishra in recent years. The Indian-born Mishra is among the best literary critics writing in English today, as well as a distinguished cultural historian and novelist. I'd read him on anything. But lately he's strayed near the pundit zone, writing political op-eds for outlets like The Guardian and Bloomberg View. To be sure, he acquits himself as well as anyone in the field. He's a consistently sharp and independent thinker, unafraid, for example, to criticize the Indian government's authoritarian tendencies and highlight the ways in which its economic boom has bypassed whole sectors of its population. But the road to membership in the technocratic elite is paved with this sort of well-remunerated pontificating, and one hopes that success doesn't diminish, as The New York Times recently described it, Mishra's “sometimes ferocious instinct for the jugular.”

At first glance, Mishra's latest book, From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia, is a sign of his commitment to the concerns that he's addressed throughout his career. The book is a survey of Asian intellectuals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and their role in pan-Asian, pan-Islamic, and anti-colonial movements. And it begins with a shot: the spectacular Japanese naval victory over Russia at the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905, which electrified Asians and Africans living under the yoke of colonialism and, in Mishra's view, inaugurated “the recessional of the West” that continues to this day.

That the West is in some form of decline isn't much in dispute. But Mishra advances the discussion by arguing that the West's moral decline traces back a century, through two world wars, a horrific legacy of colonialism, and a failure to treat non-Western nations as equal partners. This moral decline matters, he claims, because it reflects how Western liberal democracy may not be suited to these societies. Instead, these nations have looked to other models—in earlier generations, Meiji Japan and post-Ottoman Turkey, and, more recently, quasi-Islamist Turkey and China's one-party, hypercapitalist state. Given the West's recent history of economic instability and military intervention in the Muslim world, this search for other models of development—ones that, for example, acknowledge the centrality of Islam in some cultures—takes on particular significance.

The book focuses on three Asian intellectuals—Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838–97), Liang Qichao (1873–1929), and Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941)—with appearances by Ho Chi Minh, Mao, Lenin, Gandhi, and a host of less well-known Asian intellectuals and statesmen. Each of the three principles anchors one of the book's sections, but Mishra doesn't treat this as a group biography. That is at times a necessity (many details of al-Afghani's life are lost or obscured), but From the Ruins also becomes strangely fragmentary, its protagonists disappearing for a while as Mishra describes Western powers' carving up of China or the epochal disappointment of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

This is all too bad, as the book would benefit from a more cohesive narrative. Mishra is at his best when he's able to tie his intellectual eminences to the battles being waged around them. But while we learn, for instance, that Liang Qichao traveled to the Paris Peace Conference, we read little about what he was doing there or his personal reflections on its outcome. The section on Tagore does offer some particularly fine moments, such as this bit from when Tagore was welcomed to Tokyo by a delegation led by Japan's prime minister. Unimpressed, Tagore announced, “The New Japan is only an imitation of the West.”

Mishra's critiques of Western attitudes toward Asia are persuasive and he does a fine job showing how al-Afghani and Liang struggled to be taken seriously by the reformers and statesmen they courted. Some readers will likely take issue with the prime role that Mishra is willing to delegate to Islam, but he forcefully argues for its importance in binding peoples together, especially beyond the mantle of nationalism. What's more is that there are many Islams, political or otherwise, and one need only look at the relatively unchallenged influence of Christianity in contemporary American politics, as well as the attendant hysteria over sharia in states like Tennessee, to find pots calling kettles.

Where I take issue with Mishra's treatment is how in indicting the West for its colonial barbarism, he sometimes elides the crimes of post-colonial regimes. He does criticize Iran's authoritarianism and says that the Beijing Consensus “sounds suspiciously like merely a cynical economic argument for the lack of political freedom.” But in his rather admiring examination of the Turkish and Japanese models, he comes close to justifying their worst behaviors.

For example, Mishra writes that during WWI, “harassed by Armenian nationalists in the east of Anatolia, the Turks ruthlessly deported hundreds of thousands of Armenians in 1915, an act that later invited accusations of genocide.” After decades of oppression and state-sanctioned violence, some Armenians did revolt against the Ottoman state during the war. But as Mishra should know, the Armenians were subjected not only to deportations but also to wide-scale massacres, dispossession, and starvation, leading to as many as 1.5 million deaths. Corroborated by extensive scholarship and documentation, numerous historical organizations and governments have acknowledged this as a genocide, yet Turkey's vociferous, ongoing denials have left unfortunate wiggle room for otherwise respectable writers.

Mishra also cites Turkey's failed accession to the EU as racially motivated and perhaps a reflection of how Turkey's “model of indigenous modernity” leaves the West feeling threatened. Turkey has a legitimate grievance, but Mishra fails to acknowledge Turkey's curtailing of free speech, its violent conflict with Kurdish separatists, and its genocide denial.

The book's discussion of Japan's imperial era is also problematic. Mishra mentions some Japanese atrocities and makes clear that Japan's promises of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere during WWII “were often meant to give cover to old-style imperial exploitation of local resources with the assistance of native collaborators.” But he goes on to say that “many Japanese officials brought sincerity and determination to the liberation of Asia,” training local leaders and administrators and paving the way for self-rule. “In most countries they occupied,” Mishra adds, “the Japanese deeply undermined the European power that kept the natives in a permanent state of submission.” And yet, by Mishra's own summation, it's easy to conclude that subjugated Asian peoples simply traded a colonial master from the West for one from the East. Many defenders of British colonialism—such as Mishra's bête noire, Niall Ferguson—argue that colonial administrators had good intentions. And the legacy of Japanese occupation endures: visits by Japanese officials to the Yasukuni Shrine—which includes a number of war criminals among the dead it commemorates—still draw angry protests from China and South Korea.

These are not damning offenses, but they reflect the tenuous line that Mishra has drawn. A critic of Samuel Huntington’s “Class of Civilizations” thesis, Mishra sometimes finds himself, however unintentionally, falling into its trap. The historical relationship between East and West has often been based on conflict, expropriation, manipulation, and ruthless competition. Mishra is interested in finding some new syncretic paradigm for the global order—universalist in character, but respectful of local cultures and needs. His learned and passionate, but ultimately uneven, book signals that we have some way to go.